“Test for your application.” So runs the common coda that ends many of our emails and closes our conversations. At the most fundamental level, it simply means trying out a new material or technique in a way that closely mimics how you hope to use it. Other times it requires being something of sleuth and a forensic scientist of the fine arts. In the pages that follow we will examine some of the basic concepts behind testing and explain how it can help plan your procedures, solve problems, and increase your knowledge.

Perhaps the first question is why we would ask you to test in the first place. After all, don’t we already generate Tech Sheets for almost everything we make? And doesn’t our crack Tech Support team stand ready to answer any question you might have? The truth is, no matter how thoroughly GOLDEN’s Technical Support and Labs put materials through their paces and develop best practices, unique situations inevitably arise and possible combinations of materials and techniques constantly expand beyond the horizon of what we safely know. In those instances it is important to have the ability to examine choices and weigh consequences. There is also an element of education and ownership at play here. By becoming involved with your materials at this level you gain more control over your processes and a greater command of your materials.

Certain basic features run throughout any type of testing and it is important to establish these at the outset. One of the most essential is the concept of a ‘control.’ Put simply, a control is a standard or primary condition used for measurements and comparisons; for example, an unmodified state of a material, the initial starting condition of a surface, or even a desired result you can judge other trials against. A second feature is record keeping. Keeping accurate records is essential so tests can be repeated, solutions recreated, or to help us understand your procedures should you need to contact us.

Common items might include:

- A timeline and accurate description of each step in an application

- Precise list of materials, including any relevant batch codes (see illustration on right) or purchase dates

- Ratios used in mixtures

- Environmental conditions at the time of testing

- Size of the pieces

- Personal observations

All too often the essential variable will be a small detail the artist has overlooked or dismissed, so be as thorough as possible. Along with written notes, other documentation such as photographs, retained wet samples of the products, and physical examples of any problems or test results, can all be crucial. And of course, make sure to label everything accurately and keep all these materials together and stored safely for future reference. By which point you must be thinking we are simply out of our minds. “We want you to do what?” Even remembering to floss one’s teeth might be an easier task. But don’t give up yet! Doing even a small amount of the above will still put you well ahead of the curve.

- The third task is to design the actual tests themselves. Before starting, decide on your goal and parameters:

- What do you hope to achieve by the end?

- Is the undertaking meant to be open-ended and exploratory or does it need to be extremely focused with a great deal of precision?

- What are the known variables or properties you intend to test?

Make sure to write these out, being as exhaustive and thorough as possible. Conversely, are there ones that need to be minimized or ruled out? For example, you might find you need to control the temperature or have a surface be perfectly level. These and other questions are essential to setting the limits and scope of the test. A common mistake is to rush through this stage. Don’t. Taking time at this level will save significant effort later on and your results will only be useful if the tests leading up to them have been well thought out and planned. Still unsure of the best way to proceed? Feeling absolutely convinced your original hunch that we were completely bonkers is confirmed? Contact us – we would be more than happy to help you with your plans.

Inevitably the moment will come when you will need to create some surfaces to paint on. Fortunately they do not have to be fancy or elaborate and usually simple, well-prepared panels or canvases will do (see our Tech Sheet on “Preparing Painting Supports”). However, there are times when these will also need to reproduce the qualities or procedures you are testing as accurately as possible. In either case, before starting, create a checklist of materials and each step you will need to take. And plan ahead for any supplies. It is often critical to use the same materials and follow the same procedures for each piece in order to limit any variables as much as possible. In addition, having access to the exact products used in a problem area – ideally from the same container or batch – can be invaluable for troubleshooting. Scale is another factor not to overlook. Can you get the information you need at the scale you are working? Testing something on a 12″ square panel, for example, might not give you the information you need for planning a mural. Lastly, when tests get complicated or take a lot of time it is easy to lose track of the process, so remember to check off each item only after it is completed.

In the end, keep in mind the very real limits of reliability. Unless willing to undertake extremely controlled and

thorough testing, over a long period and under various conditions, the tests will not always guarantee perfect results or dependable solutions. However, they will still play an invaluable role in uncovering problems, narrowing down possible solutions, and providing new insights.

Some Basic Tests

In our contact with artists certain topics are constantly repeated. What follows are some of the most common and useful tests for tackling these issues, grouped under the following broad headings: General Materials and Applications, Adhesion, Varnishing, New Media, and Troubleshooting.

General Materials and Applications

Stop for a minute and ask yourself: How important is this piece to me? Do I know what can go wrong? Do I need to be confident about the results or do I thrive on the unexpected and experimental? Deciding on the level of risk you are comfortable with is crucial at these moments.Wondering if you can roller-apply a gel on top of a finished mural? Curious how a texture will look on a piece of furniture? Ready to apply an isolation coat for the first time to a painting?

Or perhaps your questions are simply about the materials themselves. What is the difference between these two mediums? How long will it take for a ½” layer of Molding Paste to dry? Regardless of the type of question, whenever trying a new process or product it is important to familiarize yourself with the properties of the materials. And taking the time to create practice panels will not only allow you to uncover unforeseen problems or unexpected results, it will help make sure everything meets your expectations before launching into an often irreversible process. They will also form an invaluable reference for future use.

These panels can take many forms, depending on the materials and applications you are exploring. A useful starting point might be creating a board displaying the basic qualities for each medium and gel you use; or what us lab folks have officially dubbed a ‘Product Review Board.’ To do this, start with a properly prepared substrate painted with alternating black and white bands, placing a sample of each gel or medium you use so it extends over both the black and white areas (see picture). This will allow you to better gauge the degree of

transparency once it’s dry. Take note of its thickness, rheology, leveling, and hardness when fully cured, etc. Next to this, place a sample of the same product mixed 10:1 with a color. Remember to label each pair carefully. As you acquire new products you can add to this board or start a new one. In the end you will have a useful, quick reference for the basic properties of each material.

Another simple and practical guide is to create a card for each color you use. Using a palette knife, apply the color full-strength to show its mass tone, and then scrape the paint over the surface to reveal the undertone. Next, mix one part color to ten parts Titanium White and apply this to another section of the card. Not only will this show how the color looks in a tint but will indicate its relative tinting-strength as well. Lastly, mix one part of the color to ten parts of a Gel or Medium, placing this on the card as well to show how the color appears when made more transparent.

Adhesion

Beyond these sample boards and color cards there are many occasions when creating practice panels will help avoid disappointment or even disaster. Too many large murals, extensive faux finishing projects, or important paintings are irrevocably ruined because the artist did not take the time to understand a new material, tool, or procedure beforehand. When generating these panels it will be important to create the same conditions you will be confronted with. Working on a smooth absorbent surface, for example, might not provide the information you need for a sealed rough texture. Doing small pours on a stretched canvas will not be the same as large ones on wood.

‘Will this stick to that?’ is one of the most frequently asked questions, and almost always involves points of

transition, places where different materials come together. These areas can include the adhesion of the primer to the substrate, the paint to the primer, and ultimately the varnish or topcoat to the paint. It can also concern the adhesion of various materials being used in the artwork itself, especially in collages and multimedia pieces where disparate materials are often brought together. All of these represent junctions where pieces are at their most vulnerable to delamination.

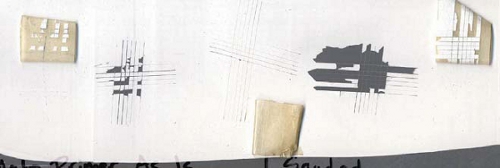

Area on right (a) was tested after 24 hrs, the left (b) after 48 hrs, and the middle (c) after 72 hrs.

Results show greatly improved adhesion over time and why you need to take this into account.

Most testing for adhesion can be done with a very straightforward and simple procedure called the Cross Hatch Adhesion Test. This method is adapted from the ASTM Standard D3359 and requires a minimum amount of preparation and tools. You will need a single edge razor or X-Acto™ knife, masking tape, and a test piece or representative surface. Prepare your support and apply the materials in the same manner they will be used. If applying layers that might prove visually indistinguishable, such as white paint over a white primer or gloss varnish over a glossy layer of gel, you should also lightly tint one of the products so you can tell them apart. Let dry for a minimum of 72 hrs. In a space of approximately 2 square inches, score a series of parallel lines about 1/8″ apart. Then score another series (perpendicular) across the first ones, creating a crosshatch pattern of little squares. By far the most difficult and critical part is making sure you only cut through the topmost layer of material. Finally, take a piece of ordinary masking tape, place it over the section and burnish it well with a fingernail or the back of a spoon, then peel the tape straight back upon itself at a 180 degree angle (see above image). If no squares lift off, you have excellent adhesion between all layers. If a few squares come off but the majority remains, you may have sufficient adhesion. However, you might want to retest with a longer period for drying or look to other means to increase adhesion. If most or all of the squares come off, this suggests adhesion failure and significant steps are needed to remedy this.

As an example of how this might be used, let’s focus on the adhesion of acrylics to a non-porous surface like glass when varying percentages of GAC 200 are added to the paints, which is one of the more common questions. Start with a thoroughly cleaned piece of glass similar to the one you will work on. Divide this into five equal sections and in the first section apply the paint ‘as-is.’ This will be our control. In the other sections apply the paint mixed with additions of 10%, 25%, 50%, and 75% GAC 200. Let dry for at least 72 hrs, since we know acrylics only reach maximum adhesion over time. Afterwards conduct the Cross Hatch Adhesion Test to each section and record the results. Did any of them have sufficient adhesion for your needs? If so, does this solution need to be tested for additional factors, such as the ability of the adhesion to survive changes in temperature or exposure to chemicals? If not, try the test again using similar glass that has been etched, sandblasted, or coated with a specialty primer made for slick, non-porous surfaces.

Varnishing

Common cases where failure to test has led to problems include working on surfaces that have been previously coated with an unknown primer or varnish, working on an unfamiliar material, or not taking into account environmental, chemical, or other conditions that could adversely affect an initial bond. For example, simple adhesion to glass is one thing; adhesion that is dishwasher safe is something else. Paint that sticks quite well to stone might fail if this is part of a fountain that will be submerged in water.

Varnishing is by far the most common subject we are asked about – either with inquiries about procedures or when there is a need to troubleshoot or fix. While GOLDEN continues to conduct testing around this subject, there are many things you can do to increase success.

An often overlooked area for testing are the visual changes caused by the application of an Isolation Coat or Varnish, especially in regard to the surface texture, sheen, and the resulting value and saturation of the colors. All of these will inevitably be altered when using either or both of these materials, so understanding the degree and manner of change will help you decide which process and product is right for you and what level of change is aesthetically acceptable. Another major area is the method of application. There are a variety of techniques and tools to work with, so figuring out which ones are best can take time and practice. It is critical these questions are explored and answered before varnishing anything of importance.

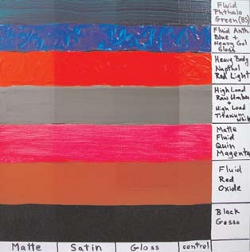

To understand how the appearance of your artwork will be affected, create several test panels composed of parallel bands of typical colors and surfaces found in your work (see image above). Eventually you will be applying a second set of rows perpendicular to these that can explore whatever variable or method you want to test. Of course, make sure to always leave one area untouched and clearly mark each section for later

reference. It is also essential to try and limit any variation to the one variable you want to test. For example, when exploring the effect of different sheens, don’t vary your method of application. That way you will feel more confident the changes you see are caused solely by the sheen and nothing else. The same would hold true if testing application methods. If wanting to see which type of brush works best, or how varying the dilution of the varnish might effect open time and leveling, keep other variables at a minimum.

Let’s start by testing how different sheens might affect your work. Take one of the panels you created and divide it into four equal areas. Remember, one area should be marked as the control and left unvarnished. Over the other three areas apply either a layer of Gloss Varnish or an Isolation coat, as discussed in our Varnishing Guidelines. This will assure that the surfaces are fully sealed and no longer absorbent. Let dry for 24 hrs. Now apply a Gloss, Satin, and Matte Varnish respectively to each of these areas. After these fully dry divide each section in half and carefully apply a second coat of each varnish. You now have a useful guide showing a range of sheens created by 1 or 2 coats of each varnish. Similar test and practice panels can easily be set up that focus on isolation coats, varnish removal, comparing spray to brush applications, etc.

In the ever expanding world of digital prints, book arts, collage, and multimedia work, materials are often employed that have unexpected or unknown properties. Compatibility becomes an ongoing concern as these newer processes and products are combined with traditional mediums. Very often, because little or no previous testing has been done, you are forced to deal with many unknowns.

New Media and Techniques

One popular medium many artists are using now is digital inkjet and Giclee prints. An area often in need of testing is the sensitivity of the ink or substrate to various products, in particular water or solvents like Turpentine and Mineral or White Spirits. To accomplish this, create a test print using the same substrate and inks as the finished work. To standardize your test and make examining changes easier, we recommend making a print using bands of the individual inks your printer utilizes. For example, most common inkjets use a minimum of four colors – Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black – while a Giclee usually has up to seven distinct inks. If space allows, you can also include rows of blends and mixtures that might be more representative of your palette. It is also important to create crisp sharp edges between each of these areas so you can judge if any bleeding or blurring of the inks occur. Once this has suitably dried, apply the materials you are anticipating using, prepared and applied in a representative manner, again in distinct rows but this time working perpendicular to the first ones – always remembering to leave one section blank for your control (see image on right). After these layers have dried examine the print for any evidence of bleeding, blurring, or discoloration. Also note any changes to the value, particularly of darker colors where a gloss or matte coating can create significant shifts in appearance.

A related test involves seeing how many layers of a particular coating is needed to seal the print so one can work on top of it without fear of disturbing the underlying image. In that case, you would first generate your test print as before. Mask off one area for your control and then apply one coat of the varnish or protective coating to the rest of the print. After this is fully dry, mask off an additional section and apply a second coat to the remaining areas, repeating this process for however many layers you wish. Once everything is dry you can apply whatever materials you hoped to use on top and gauge which number of coatings provided adequate protection.

Other mediums besides digital prints also need testing, such as watercolors, drawings, collages, traditional photographs, oil pastels, and fabrics. Each of these might require you to adapt the above procedure differently, although the principles will always be the same: create a test piece, save or mask an area to act as a control, then create a series of precise variations involving one variable or material. Some of these tests will be

simply to see how applying a new technique or material affects the look and nature of the medium. This is especially true with something like watercolors or pastels, where application of a varnish or other materials is non-removable and can significantly alter the traditional appearance and nature of these media. Fabric might need to be tested to see if the dyes are prone to bleeding or how a medium might change its texture. While oil pastels will need testing for compatibility, adhesion, and whether materials like varnishes can ever be safely removed without affecting the wax content.

Troubleshooting

Troubleshooting has special requirements that can differ from the examples we have seen so far. In those cases you generated test panels to explore a material or process beforehand and to avoid unforeseen problems. Here, however, the problem has already occurred and you need to discover a possible solution or understand the root cause so an alternative procedure can be worked out.

Some common examples might be:

- You have applied a matte varnish and are unhappy with how the picture looks. Would applying a layer of gloss solve the problem by returning the painting to its original state?

- You sometimes get hazy areas when applying a clear coat of a medium, but it seems to happen mostly in the winter. Could this be caused by changes in the temperature or humidity?

- You notice some underlying colors lift whenever applying washes on top. Would waiting longer or adding additional medium to these colors help?

All of these are very real situations you might have experienced at one time or another. When they happen you will need to try and reproduce the problem as closely as possible. This can be a challenge in itself and recalling whatever you can about the procedures, environmental conditions, and the materials you used will frequently be the first step. Afterwards try to mimic the troubled area as faithfully as you can, creating several copies whenever possible so you can begin to isolate variables, compare different solutions, or perfect a particular remedy before implementing it. Most importantly, have patience; these tasks can be demanding, difficult, and time consuming to execute.

Conclusion

As a manufacturer committed to the lasting legacy of art we continually undertake extensive original research and create guidelines for best practices. But there will always be an equally critical role for you to play in testing your own applications, where success and failure is often about aesthetic issues as much as technical ones. And of course, new techniques and materials will present the artist with their own learning curves and skill-sets to master. In addition, even when the testing of our own products has been very thorough, other materials are constantly changing. The primer that worked wonderfully under our paints last year might have been reformulated since then and is no longer suitable. Our hope is by giving you the resources and support to conduct your own testing we can allow you to have more control and be more involved with the choices you confront. Finally, if you have decided none of this is for you, that this issue of Just Paint is destined for the dustbin, still keep our Technical Support number handy. It will serve as a reminder that, no matter what, we will always keep “testing for your application” and be happy to help in any way we can.

About Sarah Sands

View all posts by Sarah Sands -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post