If a single color embodies the dividing line between pigments considered suitable for permanent works of art, and those that are suspect and poor in lightfastness, Alizarin Crimson (PR 83) would be it. And yet it is still used by many artists who are drawn to it in spite of its many problems. Some of that is driven by tradition, habit, and a sense of something special and unique about its color; a feeling that it exudes a natural earthiness and that more permanent substitutes can often appear too ‘clean’, or too high chroma, to be a perfect replacement. All of that is partly true and are among the reasons we still offer it in our line of Williamsburg Handmade Oil Colors. But the truth also persists that it has a marginal Lightfastness rating of ASTM III, or Fair, and that using it – especially in tints or glazes – runs a real risk of fading. Just how dramatic that can appear, and what might be done to help, is the topic we want to look at briefly.

If you are not familiar with how Lightfastness is measured, we would encourage you to first read our short Just Paint article on “Delta E: A Key to Understanding Lightfastness Readings”. However, while that explains how changes are measured and how those line up with ASTM Lightfastness categories, a few additional points will help make the test results clearer. The first and more surprising for many people is that lightfastness for artist colors are always based on how a pigment performs as a tint, in the case of oils or acrylics, or as a light wash for watercolors. The performance of a full-strength mass tone is never taken into account when following the various ASTM Standards for artist materials, such as D4302 for Oils, D5098 for Acrylics, and D5067 for Watercolors. However, it is something we always choose to include as it can offer additional insights about a color’s durability.

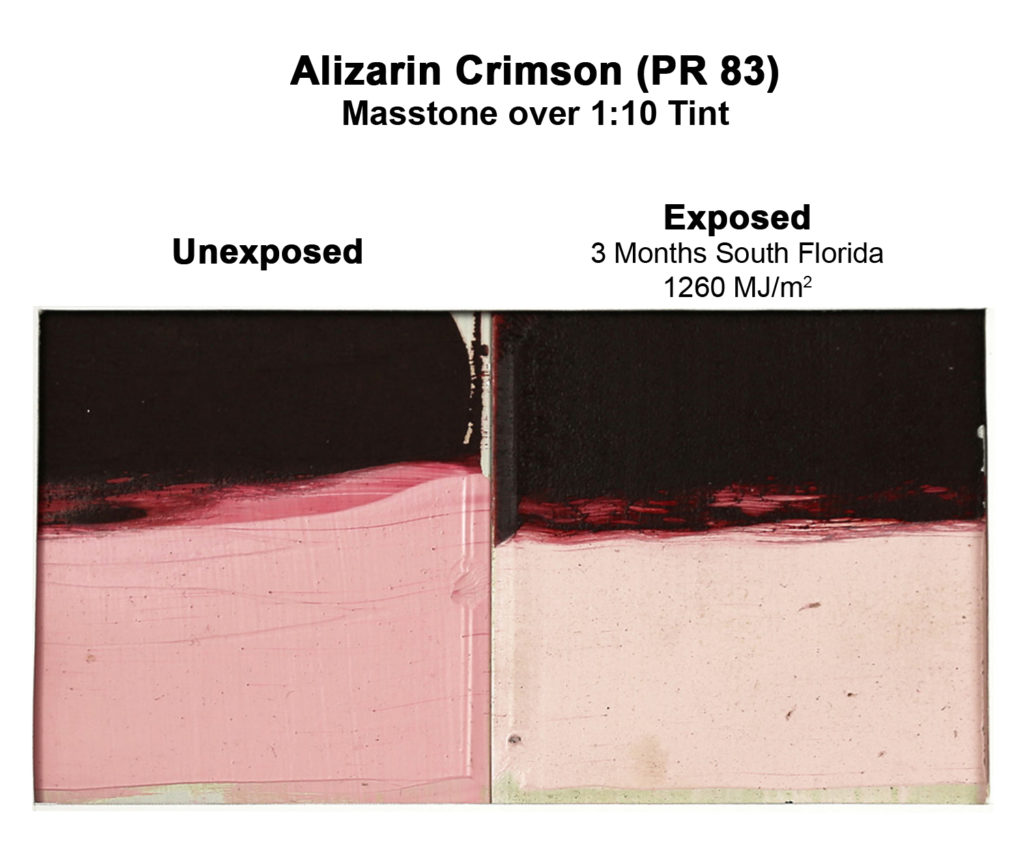

For example, in Image 1, you can see the results for Alizarin Crimson in oils, in both mass tone and 1:10 tint, after three months of outdoor exposure in South Florida, which approximates the amount of fading you can expect in roughly 100 years of museum-lit conditions. While the tint exhibits major fading, with a Delta E of 13.72 (well within ASTM III range), the mass tone actually does quite well. This goes to show that Alizarin Crimson, at least within oils, can actually perform in a very acceptable way when used full-strength, with test results showing a Delta E of 5.72, or the equivalence of a strong ASTM II Lightfastness rating.

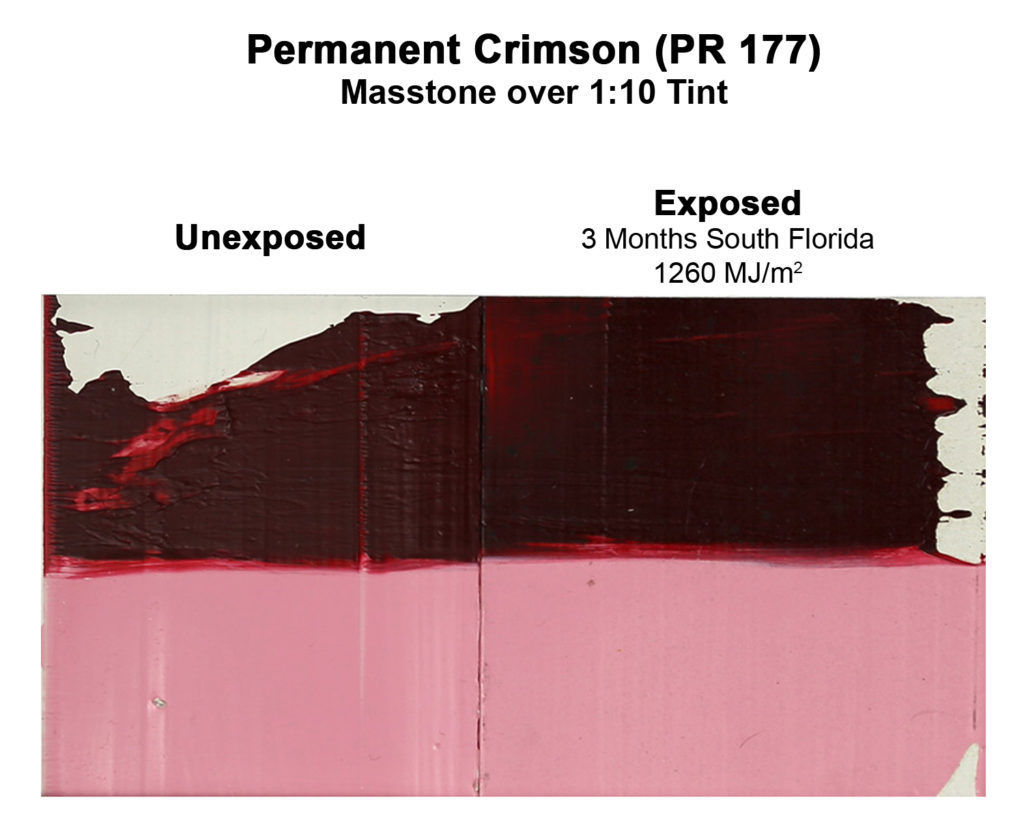

However, if needing to use the color in tints, glazes, or as a small component in a blend, or if simply wanting to work with the most lightfast choices, it may be better to use our Permanent Crimson (PR 177), seen in Image 2. A modern synthetic anthraquinone pigment, it creates richer, cleaner pinks and purples, while being rock solid in lightfastness, with the tint displaying a change of just 1.31 Delta E – the equivalent to a very solid rating of ASTM Lightfastness I, or Excellent. If needing to tone down the resulting color to more closely match the traditional Alizarin Crimson, adding a whisper of Phthalo Green can be helpful.

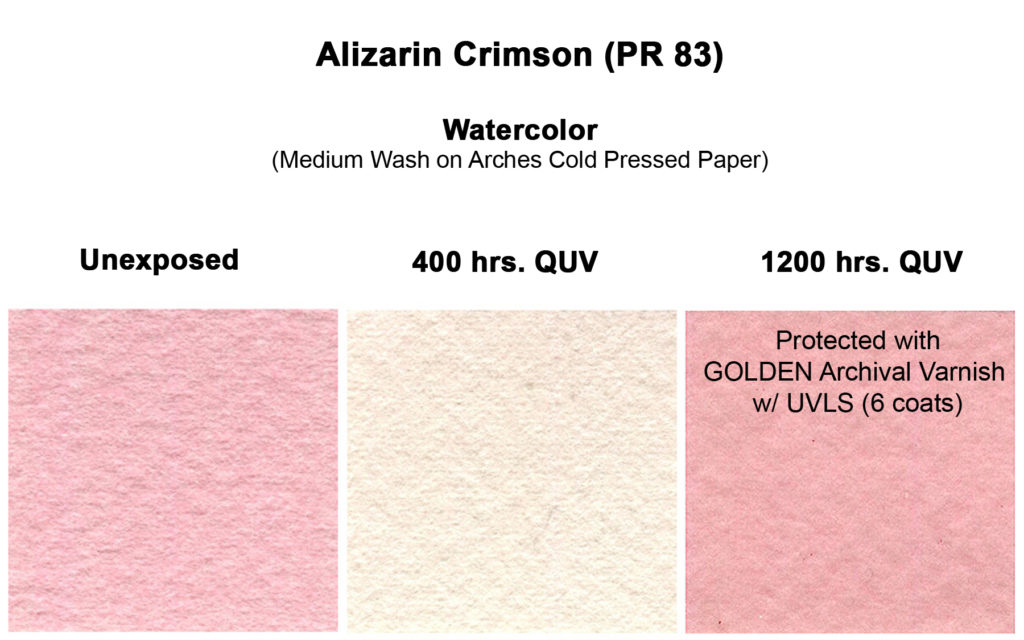

In watercolors Alizarin Crimson is even more vulnerable since the pigments are not encased in a binder and lay scattered over the surface of the paper, leaving them more exposed to UV and light in general, not to mention environmental conditions. To show just how dramatic the fading can be, we have chosen to display the results of a moderate wash, which is deeper and more pigmented than the much lighter wash called for in the lightfastness section of ASTM’s D5067. As you can see in Image 3, even this more substantial wash turned nearly completely white after just 400 hrs in a QUV Chamber, which roughly simulates the amount of fading one would expect after 33 yrs of museum-lit exposure. But there is also some good news. The third swatch shows results when the wash of Alizarin Crimson was protected by 6 sprayed coats of our Archival Varnish with UVLS, to see just how effective the protection might be, and we were pleased to see that after 1200 hrs of exposure – or the rough equivalent of 100 years of museum-lit conditions – the color held up fairly well, with a Delta E of just around 2.0, or the equivalence of ASTM I, Excellent. However, this degree of protection also comes at a cost, as the sense of the uncoated, delicate paper surface was lost and the color was clearly altered in the process.

So where does this leave us? More testing is definitely needed to fully understand how effective UV filtering varnishes might be for lighter tints and glazes of Alizarin Crimson in oils and other media, and we should remember that accelerated testing is never a guarantee that these will be the actual results in the real world since the variables are simply too vast to duplicate. Until then, this venerable and historic color should be used with great caution and with the full understanding that it is vulnerable to fading and is considered by nearly every expert in art materials and conservation as having poor lightfastness, and could even be considered highly fugitive depending on how it is used. If you do use this color, keep it as strong in tone as possible, limit its use in glazes and tints, and by all means when possible either varnish the piece with a UV filtering varnish or mount it behind a museum-grade UV filtering glass or acrylic sheet.

This is fascinating, and I feel crucial information to watercolourists in particular. The scientific perspective of painting is not high on the list of priorities when teaching or learning, for the most part, I believe. All related information I have discovered over time on my own.

My comment is about the watercolour paints tested. A binder or brand was not given. I was wondering if older, gum arabic binders existed in the samples here, or whether the QoR Watercolours by Golden were used. I have switched to using QoR Watercolours exclusively. I have often wondered at how one would finish a watercolour with some protection against the elements, mainly moisture. I was hoping that you could name the type of watercolour used, if only by the binder. Also, how would QoR (permanent) Alizaron Crimson, which is included in one of the sets, fair in this test.

I may have answered my own question. It is labeled Permanent,…Alizaron Crimson. I would still love your feed back on QoR’s lightfastness in general.

I plan to share this article with all the watercolourists at the studio (:

Thank you Golden!

Hi Teresa –

Thank you SO much for the words of appreciation! We truly appreciate it and of course plan to publish many more articles relevant to watercolorists and about the lightfastness of pigments in the months and years to come. So stay tuned and definitely subscribe!

The Alizarin Crimson we show was a special batch we made using the same Aquazol binder in our QoR watercolors. However we did test a well known gum arabic version alongside it, just to make sure the binder did not make a difference, and the dramatic fading was the same. As too the amount of protection afforded by our Archival Varnish. So we are confident the binder plays no role, in this instance at least.

As for QoR’s Permanent Alizarin Crimson, that uses the same PR 177 pigment we showed in the oil color example, and when we tested it in QoR the results were similarly impressive, so we have full confidence in recommending its use as an alternative.

Hope that helps and if you have any other questions, just ask! And again, thank you for your enthusiastic response. It means the world to us!

Hello Sarah, I enjoyed your post on Alizarin Crimson. It’s problem has been known since the 1990’s but there are many artist that are still not aware. I recommend the Permanent Alizarin or a Quinacridone Magenta as a substitute. Thank you for sharing this post and the visuals of the result of exposure to UV. I was particularly interested in the result of the watercolor sprayed with the Golden Archival Varnish. Do you have any VisiCalc results of an Alizarin Crimson tint with an application of the same varnish? That would be interesting especially for those artist that are not aware and still use the color in their oil paintings. Regards, Ed S Brickler. PS: Mark, Patty and Bill Hartman know me.

Hi Ed – Always a pleasure to hear from you and will definitely pass along hellos to Mark, Patty and Bill. When you say VisCalc do you mean spectrophotometer results? I know ViswCalc mainly as a reference to spreadsheets so any light you can shed on that would be great. As for results with an oil-based Alizarin Crimson with varnish, I do not have anything official that I could share but will try to generate a few examples and put them through the same exposures and see if we cannot share those results as a follow-up in a few months. So definitely stay tuned. And if there is anything else we can do, just ask!

I was an user of Liquitex and a wonderful teacher (Melanie Mattews) gave a workshop with your products. I was very impressed with the easy versatile and the good results of your products! Now with Golden I can work and have the same result of a technic time after time. I give you the best note A+++ at your research team and stay the best.

with pleasure

Sylvain

Hi Sylvain – Thank you SO much for the wonderful feedback. And yes, Melanie Matthews is definitely one of the best, so you are not alone in having been introduced to our paints through her incredible workshops and demos. Thanks again for taking the time to share your warm words and feedback, and if there is anything else we can ever do to help, just ask!

Good presentation. There are other colors that change with time and different tempatures.

Hi Ricardo – Thank you for taking the time to comment. And yes, pigments definitely change in many different ways.

Hello Sarah,

This is a huge fan of Golden paints since 1997.

Somewhat recently I have tried to branch off some of my work towards oil painting. Did I understand you to say you have a line of oil paint? If so, I need information on how to protect a fairly recent painting I finished last winter. I want to finish or rather finalize my work correctly before I frame it.

Please email me a response privately.

Thank you for you continued support with my painting adventures!

Sincerely, Agnes

Hi Agnes – Thank you for the comments. I will email you privately with the information you need.

Sarah, thank you for this information. I am an absolute beginner to painting and this information is very helpful as I know absolutely nothing about paints and how they work or last. Again, thank you.

Hi Linda – You are SO welcome and thank you for taking the time to let us know that this type of information is helpful. And as always, if theree is anything else we can ever help with, just let us know!

Hope you don’t mind if I use some of this information and maybe an image in a seminar I will be doing at The Studios of Key West in late January. The subject is Care of Artwork in a Tropical Environment and one of the areas I will be covering the effects of light on paintings. I am handing out information on suppliers also and you will be included. Carl Plansky ( of Williamsburg) was a good friend of mine and I was his framer for many years also. Remember his basement where he began well!

Hi Judith –

How wonderful to hear from someone so connected to Carl Plansky! I worked alongside him through the mid 90s to early 00s and have many fond memories of that time. In terms of using images or information from this posting, let me forward your request to the person who handles that here, Jodi O’Dell. She should be in touch with you sometime early next week. In the meantime thank you so much for taking the time to comment and let us know that this information is of value.

Thank you Sarah! I do like to recommend products that will aid the artists in giving their works longevity so will carefully go thru your products and would be delighted if your company would make recommendations. Look forward to hearing from Jodi and appreciate your time.

I think this is interesting. Because I see many people use Alizarin to lower the saturation of a phthalo green yellow, or a permanent green light….I always wondered what would happen if the Alizarin faded…

Especially now that we have industrial strength greens like phthalo. Isn’t the green just going to revert back to full strength saturation prior to the mixture once the Alizaron faded?

I wonder, since I use black and white to modifie saturation and value instead of complements, if I am more protected from these problems (also in terms of drying shifts)…

Hi Olivia –

So glad that you found the article useful! In terms of your question, yes, as the Alizarin Crimson fades the Phthalo Green or other color will become more dominant. How much the Alizarin will fade, or at least how fast it does, will largely depend on its percentage in the mix, as well as how thinly it is applied. And so yes, you are more protected by using black and white instead of Alizarin Crimson to modify saturation and value of a green, for example, however Alizarin is not your only option if wanting to explore how compliments can modify each other. Instead of Alizarin Crimson simply use our Permanent Crimson and you will get similar results that are much more permanent.

Hope that helps!

Hi Sarah,

First of all, thank you so much for all your articles on lifghtfastness (and the other ones as well). They have been a great source of information for me in my job as a conservator.

I question, I am currently working in a project testing lightfastness of artist’s fabric paints. We’re using an old Atlas Ci35 Fade Ometer with a Xenon-Arc lamp running at 420 nm at aprox 0.9 W/m2.

I’m having some difficulty converting the numbers and units to make them make sense to me and applying them to the Blue Wool Scale.

Do you know of any good ways or a table to convert for example (kJ/m2)/hr to lux/hr?

Kindly, Ann-Sofie

Hi Ann-Sofie –

Thanks so much for your patience! I appreciate it. Unfortunately, as you have already sensed, there is nothing easy about converting from irradiance (kj/m2) to lux, or even lining up Blue Wool results, where exposure is generally based on lux, to something like the ASTM Lightfastness Standards (D4303) which are tied to a total solar irradiance of 1260 MJ/m2 for outdoors, or for xenon, 1330 KJ/m2 measured at 420nm at .90 W/m2 (see Table X-1.2 on p. 9 of ASTM D4303). The core problem is one of moving from radiometric to photometric, or roughly from a measure of the total energy falling on a surface and the level of illumination provided by a light source. The reason this is problematic is that illumination is based on our eye’s response to particular wavelengths and how that is translated into a sense of a particular level of brightness. Thus it is concerned only with the band of wavelengths that we can see. One dramatic consequence of this is that lux ignores any measure of UV, although UV more than anything else greatly impacts fading. Thus two identical light sources, one with and one without UV, could ostensibly be measured as having the same level of lux because they would appear equally bright to our eyes. Or there is the more subtle fact that our eyes are most sensitive to 550nm (light green) and so is biased towards seeing light rich in that area as brighter – thus more luminous – than a different composition of light that might nonetheless have more overall energy.

For an example of how that complicates things, see Figure 5 on page 4 in this paper put out by Q-Lab

The conundrum is also nicely summarized on page 2 of Radiometry and Photometry: Units and Conversion Factors (http://www.randfoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Radiometry-and-Photometry-Units-and-Conversion-Factors.pdf):

Where this eventually leads one? Basically, you end up having to multiply the spectral curve of your light source by the photopic response curve, or as stated in “Converting From Radiometric Units to Photometric Units” (http://sanken-opto.com/Products/FAQ-LEDs/converting-from-radiometric-units-to-photometric-units.html):

Or see the bottom of this page:

You can also find tables where conversion factors are provided for each 10nm of wavelengths from 380-770nm, in the following documents:

What there isn’t, however, is any simple single formula or, as best as I could see, some easy app or online calculator that can do the work for you. Although one would think by now there would.

Finally, while not helping with a mathematically precise conversion, Stefan Michalski does a decent job of lining up Blue Wool results with accumulated lux exposure and correlating that, albeit broadly, with ASTM Lightfastness Ratings:

I hope the above is helpful in some way. It doesn’t solve your problem, I know, but it’s my own weird way of at least commiserating with you and acknowledging that its a problem I have not solved myself.

Wow, an enormous Thank you Sarah!

You have no idea how much this helps me. Even though it might not fully solve my dilemma it gives me confirmation that I haven’t been completely fatuous in my struggle to wrap my head around this little problem.

I haven’t fully digested all the information yet but I have already learned so much.

I don’t know how to thank you enough.

Kindly

Ann-Sofie

The pleasure is ours – and if we can help further don’t hesitate to ask. Always happy to share what we know.

The simple answer to your question is just that true Alizarin Crimson is a unique and beautiful color. And really, this is the answer we would give if this question was asked about almost any pigment and color we choose for our paint lines. It fills in a color space within that group of dusky reddish, maroon like colors, with its own unique versatility. On our Williamsburg Oil color chart, we say that this very concentrated Alizarin Crimson is versatile because it can go “sweet ( pink ) and sour ( orange ) depending on how it’s used.” There are modern organic pigments we use to make more lightfast colors remininscent of Alizarin Crimson, but it’s hard to nail the exact color qualities of true Alizarin.