While the practice of pouring artist paints is certainly not a new way to apply paint, achieving consistent results can be frustrating and costly. However, it is vital to the process to conduct experiments to gain the knowledge of what are the most critical controlling factors which preside over paint pours.

Studio Preparation

One sure way to improve the odds for successful pouring is to start with a clean studio. Acrylic pours are relatively slow drying paint layers and dust can easily become imbedded into the film. Take some time to free the immediate workspace, sweeping the floor and wiping down surfaces around the studio. Next, be sure the table top or floor you are working on is also clean and level. Even slight angles can cause issues with pours. Put down fresh poly plastic sheeting on the surface which will protect the surface and help later on by preventing your artwork from becoming glued to the work surface, as pouring products creates puddles and drips that can travel off of the canvas or panel. Finally, control the temperature and humidity level in the studio as much as possible. Dry climates increase the chance of crazes developing – fissures resulting from liquid acrylic products skinning over during initial drying while the underlying liquid paint is still very fresh. The skin shrinks and tears apart resulting in unwanted physical textures known as a “craze” (see Image 1).

Painting Substrates

The most predictable painting surface for pours is a sealed panel. This surface is less affected by the weight of the wet product compared to stretched canvas. Of course, the panel needs to be resistant to warping from water, thus sealing the surface with one or more coats of acrylic medium (or paint) is helpful. Conversely, this advice may be counter-productive if your technique relies upon the surface absorbency and/or the ability to curve the substrate in order to control the paint movement. This is why testing is such a critical factor even when using products that other artists find successful. If working on stretched canvas is vital to your process, you may be able to eliminate the sagging by stretching over a wooden panel or using a cardboard block between the stretcher bars.

Paints and Mediums used for Pouring Applications

Free-flowing liquid paints and mediums are at the heart of the pouring process. Adjusting the viscosity and flow rate to work in tandem with how you want the paints to interact with each other is key. Obviously, products like GOLDEN Fluid Acrylics and High Flow Acrylics are more practical when doing pours than thicker Heavy Body Acrylics. This is not to say you cannot use Heavy Body paints, but they will first require thinning with water, acrylic medium, or both. A great approach for thinning Heavy Body paints without a loss of film strength is to first mix a thin acrylic medium such as GAC 100 with water (1 part medium to 1.5 parts water, and then use this mixture to thin the paints as much as desired). This mixture assures quick thinning but contains enough acrylic binder so that you still end up with a pourable paint instead of a color stain mixture. Since Fluids and High Flow Acrylics are already pourable, this step isn’t required to work with them, but sometimes it is necessary to adjust these paints as well. GOLDEN Airbrush Transparent Extender is also a valuable medium for adjusting paints. This product is a similar consistency to High Flow Acrylics, containing flow improvers and leveling additives.

Although most acrylic mediums are inherently pourable, some are better suited for pouring than others. GAC 800 is a medium specifically produced to modify paints for pouring, such as when pouring a puddle onto a paint surface. The GAC 800 mixes readily with the Fluid Acrylics and this combination is the least likely to craze during drying. It’s still possible GAC 800 may craze, but this is usually the result of too much paint being added and in turn, countering the acrylic solids level or the pour has been applied in too thick of a layer. A great starting point is to mix 1 part paint into 10 parts GAC 800 and limit the thickness to how far the product will spread. In other words, pour the product into a pancake puddle, and let it seek its own thickness without impeding its flow by use of a taped off or dammed edge. Once these tests are done you may want to try other paint amounts and use edges to control the flow, but be wary of too thick of a pour to start. The biggest negative attribute of GAC 800 is “dry state clarity”. This medium retains a slight cloudy quality making it a poor choice as a clear topcoat or even transparent color layer.

Other mediums to experiment with include GAC 500, Polymer Medium (Gloss), Fluid Matte Medium, Self-Leveling Clear Gel and Clear Tar Gel. One important note worth mentioning is that these products were not developed with defect-free pouring in mind, and although smooth thin layers are possible when using them, they are not free of issues and limitations. For example, a common misconception is that Self-Leveling Clear Gel can be poured liberally and spread around with palette knives, trowels and squeegees and level perfectly upon drying. This is not the case, and some tool marks, however slight, will likely remain in the dried layer. Tool shape and application technique are critical to their success, and artists who have mastered their use have spent many frustrating nights in their studio figuring out the best application method that provides the desired results. As a place to start, use clean, large tools with smooth edges and carefully spread the product in multiple thin coats until the desired effect is attained. Allow one to three days drying between coats to reduce the chance of crazing and don’t be put off if every layer isn’t a perfect epoxy like surface, as perfection is nearly impossible to attain in layers of air drying products.

Pouring Application Techniques

There are as many methods as there are product combinations to try. First, appreciate each paint color as its own unique formula and pigments vary in their density and ability to move and spread. The same is true for the many acrylic mediums produced. Now factor in the addition of water, Retarder, or diluted Acrylic Flow Release. Toss in the impact of the painting substrate and studio environment and suddenly, predictable pouring seems unattainable. The way to best describe the approach to pouring applications is the concept of setting the stage to allow the products to do what they want to do; in other words, controlled chaos. And if you don’t take good studio notes to identify how each painting is created then you’ll never be able to reproduce a great effect when they happen. That said, here are some common methods and beginning mixtures to try out:

- Thinned Color Washes – High Flow Acrylics are ready to use for this application. The colors will readily move and interact. Try them neat, mixed with mediums like Airbrush Transparent Extender or GAC 500 and let gravity move them around. Fluid Acrylics will require at least 10% additions with water to allow them to freely move about. Note: high additions of water increase surface tension, which can be countered by adding in 2 or 3% Acrylic Flow Release into the water prior to using it to thin paints. Do not over-add Acrylic Flow Release as it does not help improve flow, it’s intended to reduce surface tension which happens quickly.

- Solid Color Pours – As mentioned previously, GAC 800 is a great medium to use with Fluid Acrylics for making colored pours (see Image 2). Ideally start around 10 parts GAC 800 to 1 part Fluid Acrylic, mix and store the paint overnight in a sealed container. This allows the bubbles incurred during mixing to rise and pop, resulting in clean pours with sharp edges. These mixtures produce clear color edges. Solid color pours can be used over an entire canvas, but avoid damming up the edges during drying.

- Adding Isopropyl Alcohol into Acrylic Paint – Alcohol is less dense than water, and evaporates quickly once it hits the surface of a pour. Unlike other applications, the alcohol amount for this technique is relatively low because once the effect happens and it escapes the fresh pour, there needs to be sufficient time for the normal acrylic paint curing process to

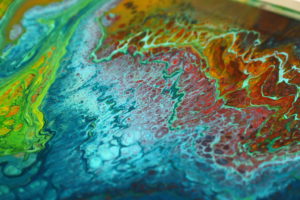

Image 3: Pours of GAC 800, GOLDEN High Flow Acrylic & Isopropyl Alcohol create cellular patterns as the alcohol tries to escape the paint during drying. occur to avoid film formation issues. An effective starting recipe is 2 parts GAC 800, 1 part High Flow Acrylic, and 1 part 70% isopropyl alcohol. Create 3 or more paint mixtures in containers which can be shaken without spilling and carefully pour one color on top of another. Dense pigments like Titanium White should be used as the final layers so that the more aggressive colors below will push up through and create the cellular effects (see Image 3).

Conclusion

As with any new painting technique, do not be discouraged if the desired results don’t happen immediately. Good note taking is critical for successful pours of acrylic paints and mediums. If you find yourself at the crossroads and need additional guidance, please contact the Materials Specialists with your questions!

About Michael Townsend

View all posts by Michael Townsend -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

Great article with useful information! I was wondering how artists were achieving the cellular look. Going to give this technique and the others mentioned a try. Thanks so much!

Hi Christine!

I’m sure you’ll have a great time. Take notes and expect a learning curve!

– Mike

Mike when using liquitex pouring medium with fluid acrylics how much exact should be used? it seems it gets to thin. Can you use this with regular tube acrylics? What is best to seal the gesso befor pourings?

Hi Ginny,

We have tested Liquitex Pouring Medium with Fluid Acrylic and Heavy Body Acrylics, so they are compatible with one another. Using Heavy Body Acrylics should result in a thicker pouring mixture, assuming enough paint is added to factor in the overall thickness.

Sealing the Gesso surface can be accomplished with many kinds of mediums, gels and even pastes. I would use a gloss product, such as Polymer Medium Gloss, but keep the layer very thin to avoid crazing.

– Mike

Thanks Michael, lots of great info!

Diane

Hi! Thanks for the great post. I’m trying very hard to get large cells to form when I do pours. I’ve watched many tutorials and tried many paint:Flietrol ratios, paint:silicone ratios and am finally getting teeny tiny cells. But I want large ones. I live in a very arid, high altitude desert and my studio has been experiencing sub freezing temperatures. I can’t control those things. Any suggestions? I’m totally at a loss.

You are very welcome, Kathleen.

It sounds like you are in a very dry area with low temperatures. One of the things you may not have tried is to add some water into the paint mixtures to help make them a bit thinner, which can help the development of the cell patterns. Do some testing, where you add 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% water to the paints you are currently mixing up, and see if you notice any improvement of cell development. If you still don’t see any positive changes, repeat, but use a medium with retarder in it, such as GOLDEN Airbrush Medium and see how that does. IF that still doesn’t work, then you may need to switch the paint brand and mediums being used. – Mike Townsend

What does a “retarder” do?

Hello Cathy.

Thanks for the question. A “retarder” is a paint additive that “retards” the evaporation of the water in the paint, effectively slowing down the paint’s drying speed. In artist acrylic paints, this provides extra blending and painting time. It is important to be careful with using retarders in thick paint layers, because it is harder for the retarder to evaporate out, which keeps the paint sticky or tacky until most of it has gone.

– Mike Townsend

Rain X + floetrol + Liquitex pouring medium + paint = cells cells cells

that rain x is a game changer, trust. 😉

Hello Cara.

Thank you for commenting.

You may very well achieve some cells with this combination, but the question is whether the RainX will also create issues for the artwork long term?

It is unknown without scientific testing confirming if adding these non-painting products will create failure for the artwork in the future.

– Mike Townsend

Hello Cara

Can you kindly give ratios of the above recipe? Thanks

If you mix the silicone in the paint very little & gently, you should get larger cells. If you mix the silicone a lot & briskly, you will get smaller cells.

OR you can leave out the silicone and after you pour your paint, take a toothpick or or a wide-toothed comb, dip it in silicone and then dip it in your paint. You should get large growing cells. You can also tilt your canvas down and as the paint is flowing down, tilt your canvas side to side to kind of keep the cells from stretching too much in one direction & keeping the cells round.

You could also add a humidifier to your work area to help with the drying. Adding silicone directly to the paint, THEN mix with the rest of your recipe. That helped me when I wanted cells. I had cells on top of cells which I didn’t like. There were just too many and they were big to small. I was using a 30″x48″ canvas and I had nightmares of circles that night in bed with how many cells were on that big piece. I had to start over and gesso, sand and do something different after that try.

Thanks Daryl.

I found that it was easier to control cells with very light spritzing of dimethicone onto the surface of paints (using a small brush) rather than adding into the colors and hoping for the best. Slowing drying time with humidity is a great thought to allow for more cells to form before the paint starts skinning over. – Mike

iF YOU HAVEN’T WORKED IT OUT YET YOU NEED SILICON OIL, LOADS ON UYOUTUBE

Hi Katie,

At this point in time we do not endorse the use of silicone oil in painting mixtures that are expected to last. There are many reasons for this stance. Most silicone oils do not evaporate out of the paint, therefore they stay within the matrix of the paint and could potentially cause film formation issues. At the very least, the silicone oil will impede the intercoat adhesion between the surface of the pour and subsequent product layers, such as mediums and varnish. As an artist, you are free to do what you want to to make your artwork, but until we gather enough evidence that there isn’t any long term issues, we won’t suggest artists add silicone into paint. – Mike Townsend

The automotive silicone works beautifully! I made my own pouring medium with Elmer’s Glue All. Would love to try alcohol but concerned it might not work with my everyday craft paints.

Hello LAC,

Thank you for your comments. Artists are free to combine materials as desired for their artwork. Our job is to try and identify any potential permanency issues likely to occur when using products never intended to be added into paint films. Silicone oil is a non-drying, non-evaporating oil. Other non-drying oils like Mineral Oil, Olive Oil, and Motor Oil are all things best left out of paint mixtures. The use of Elmer’s Glue All as your base medium, poured thickly, is likely to result in adhesion issues and noticeable yellowing.

– Mike

I tried some pours wi elders & didn’t get any cells. Do you know at I could have done wrong? And you

Hello Shelly.

Please re-submit your questions as I’d prefer not to guess what you are asking.

Thanks

-Mike Townsend

Nice to know! I was thinking of stopping at the parts store to check for some since silicone oil for painting is not available in the town I live in neither is flood.

Hi, I have been using silicone in my mixes and in Reading this I am concerned…. The silicone tends to rise during curing and then gets washed off whien acrylic is dry. Would it still affect the film formation?

Hello, Emmanuelle. Thank you for your question. While some of the silicone rises out during drying, no one knows if ALL of it comes out and reaches the surface. I believe wiping down the surface is a good idea but it may require repeating several times as the films more fully cure. We have seen this happen with overloads of surfactants, which tend to rise and collect on the surface of the paint film. So to summarize, what is truly going on with the silicone during film formation and afterward still needs to be studied, but overall try to minimize the amounts until it’s shown to be either acceptable or not.

– Mike Townsend

You don’t need silicone for cells anyway once you learn about the different densities of the different paints and how they react with other colors. #stopusingsiliconeforcells

Agreed!

Thanks, Ryan.

– Mike Townsend

Michael and Ryan,

Totally agree with you both but I am having a heck of a time learning this information. I know that Golden has a chart of their densities but do either of you know of any resources that can teach me more in depth about this? Thank you in advance!

Hello Alana.

Yes, there’s a learning curve with this painting technique and the more you try to pinpoint a specific pouring method, the more testing you need to do. Work small, take notes, and don’t be afraid to fail! I will say that density is important for this level of control, and if you make a set of paint mixtures, use a little to create 2″ puddles of one color, and then drizzle a few lines of a second color across it. You’ll be able to use this as a guide to better predict how individual colors will behave based on the sequence of the order in which they are applied.

– Mike Townsend

I would be worried about toxicity, after reading the labels on silicone lube products. Did my first pour with WD40, which worked, but was very smelly. Now I use rubbing alcohol, acrylic gloss varnish and paint conditioner.

Also torching silicone products releases hazardous fumes.

I get my cellar patterns by mixing liquid silacone also known as a lubricant such as coconut oil in to one or more paint color then once finished I use a chefs torch in a circular motion to achieve cells.

Thank you for replying to Christine, Max. Just realize that we do not endorse the use of silicone oils, commercial lubricants, or other non-drying oils with acrylics, as we do not know what it does to the film formation process or long term stability of the paint layers. This also goes for the use of a torch. The high temperature may not adversely affect the silicones but may cause film formation issues of the acrylics.

– Mike

Michael,

I have been doing experimental silicone pours and there have been a few issues but the GAC 800 finally stopped crazing issues for me. What I’ve discovered is that the oil will continue to come out of the painting for a couple of weeks and during those couple of weeks while you essentially cure the painting, you keep wiping it thoroughly in circular motions and it continues to create a nice shine. If you want to epoxy one, wait 3 weeks, you don’t want any moisture at all in the painting.

I do one coat varnish when I feel it’s cured enough. The torch stabilizes the cells you are trying to preserve in the initial pour and it helps create texture, giving an organic look, and it works better than a heat gun or blow dryer which moves the paint to much.

Thank you Kim for your insight. There is much testing to do to learn how the silicone oils are affecting the paint layer, and if enough of the oil can be removed to allow for sufficient intercoat adhesion between the paint and the varnish or topcoat layers. In the silicone testing I have done, which isn’t very much to qualify me as an expert, the surface seems very slick and not likely to allow for proper adhesion. We follow the “ASTM Cross-hatch Adhesion Test” which is one we use for many kinds of adhesion testing between substrates and primers, primers and paints, paints and topcoats.

– Mike

have you ever tried this with Acrylic glazing liquid (gloss) by Golden

Great article!! The chemistry geek in me loves getting into what’s going on behind the scenes so to speak…how & why the paint is doing what it’s doing!! Thanks for the informative article!!

One question…I mix my paints ahead of time as I love having a collection of colors available…I mix large batches of white too…my white was getting low so I mixed up a new batch & I’ve been battling the white ever since. It is rising to the top. I tried making it a bit thicker still it is overpowering…any ideas why this might be happening? I’m wondering if I got my ratio wrong…your note taking advice seems relevant here LoL!! I thought I had it memorized but as I write this I’m having some doubts…any suggestions would be great!!

Thanks so much!

Interesting, Amber.

My experience has been that the Titanium White wants to dive downward in a pour, not rise. However, if the white mixture was thinner than the other paints it would likely stay afloat or rise upwards, trying to equalize. Try using the same amount of medium to paint, and see if this helps!

Regards, Mike Townsend

I do not want cells. Is there a way to avoid when using heavy body, regular, or liquid acrylics with GAC 800?

Should water be avoided during mixture? Can you pour color combinations in a cup or can the colors be directly poured onto substrate.

Great article and replies to questions. Thanks.

Hello Michelle.

Thank you for your questions. The Fluids and GAC 800 can produce smooth color fields without the creation of cells. The 10:1 ratio in the article helps to minimize the impact of the various paint formulas, which in turn reduces the differences of the color mixtures for pouring. It can also be helpful to keep the pigment density range close together. Density differences will cause some colors to sink and others to rise. The easiest way to do this would be to work with organic pigments (modern pigments such as Phthalo, Quinacridone, Benzimidazolone, etc.) and avoid most of the inorganic pigments(metal and natural earth pigments. At least try to use one type in a painting.

Please let us know if you have any other questions!

– Mike Townsend

Can one apply acrylic paint on top of the poured surface once dried?

Hello Natalie,

Yes, once you have allowed the poured layers to become solid (typically 3 days or so) then you may hand-paint over them as desired. It’s possible you may be able to paint sooner, but the timing changes based upon environment, poured paint thickness and what you’d like to do next. Multiple pours often take the most time to reduce the chance of cracks and other unwanted surface defects occurring.

– Mike

Michael Townsend is there a chance you could send me a paint density print out like you sent to Danny Clark?

Patricia

Hi Patricia,

Yes, we’d be happy to send you the Pigment Density Chart. Here’s a link to it GOLDEN Pigment Density Chart .

I will also send you an email with this link as well, in case you don’t return to these comments. – Mike Townsend

Please send me the paint density chart

Hi Linda, here is the link to the Pigment Density CHart PDF file. https://goldenhub.goldenpaints.com/storage/uploads/pigment-density-of-golden-artist-colors.pdf

– Mike

Hello Patrica,

Yes, we would be happy to send you an email with the link. I’ll also provide it here: Pigment Density Chart

Michael

One more question, okay three questions…☺️

In order to get large cells in a pour what is the recommended ratio and/or recipe?

Doing a resin/paint combined pour would you still need silicone or alcohol?

I see many on YouTube using a torch but wouldn’t a hair dryer with a diffuser on warm/low be effective and less dangerous?

Hello again Patricia,

1- Larger cell patterns are produced by blending low density-pigmented paints with low density additives (Isopropyl Alcohol) in the lower layers, which in turn push through paints with a higher density, forcing them apart. Alcohol wants to readily escape the paint mixture and it takes the paints it is mixed with for a ride to the pour surface. This is of course assuming the paints are thin enough to allow for the rapid movement but not so thin that the developing patterns break down before the paint is able to dry. While there are other forces at play here, this is the idea behind the process.

2- I would assume that you would need the low density additive in any mixture in order for this cellular pattern to develop.

3- There are concerns that the use of silicone oil in a paint mixture can cause poor film-formation in the acrylics, and also poor intercoat adhesion for any paints, mediums or topcoats/varnishes applied over them. Therefore, we cannot endorse the use of silicone in artwork that you hope will last the test of time. Maybe it will be okay, maybe not. We just don’t know. The same reasoning goes with the use of a torch to coax the patterns to develop. We don’t know what it being released into the air, or if the heat is great enough to alter the film formation process. Heat and/or flame with highly flammable isopropyl alcohol is a very dangerous combination, please do not do this. – Mike Townsend

So you therefore do not put alcohol in the paint that is to be poured last or do you put it in all of the paints?

Hi Mike,

You mentioned patterns breaking down during drying. I’ve been using Liquitex pouring medium with Floetrol and isopropyl alcohol and a bit of water, and have varying densities in my paint. I’ve been finding that while my paintings are gorgeous prior to drying, the patterns resulting the next day are not nearly so pretty. How can I ensure my patterns stay put overnight?

Thank you!

Hello Daniel.

I find that the key to retaining the patterns in a pour are to, first, mix the paints where they are pourable but not so thin that they stay put. This includes the amount of alcohol and floetrol used. The more aggressive solvent is use, the greater the amount is evaporating, creating the changes. Second, make sure you work on a VERY level table surface, and reduce any air flow until the paint layer is solid. Do not move the artwork at all if you can. Ideally, where you pour is exactly where you leave it to dry.

– Mike Townsend

Hello Michael,

When adding alcohol to acrylic with the intention of creating cells, do you suggest stirring the alcohol in or simply add a few drops? Thank you in advance for your help.

-Tina

Hello Tina.

I’ve done both. Each gives a different look. Adding alcohol also helps to thin the paint mixture, which in turn produces more cells depending on what colors you add it to, and how the paint colors are sequenced. If I’m at the tail end of the pour and it doesn’t seem like there’s going to be enough cells, then I’ll spritz the alcohol onto the surface. Apply sparingly but in a way that creates some decent sized droplets, otherwise you’ll get more of a fine lace effect.

– Mike Townsend

Great article! Can I ask, would you put the lighter colours down first, or the darker? Wondering if the lighter blues (for example) would have enough opacity to sit on the darker blues. What generally happens here?

Hi Laura, If you are referring to the alcohol pours, colors with more opacity seem to develop more pronounced patterns. Transparent colors are darker and it’s harder to see the effect. Contrast is important, so that light layers give way to darker colors rising up through them.

This article is everything, ESPECIALLY the end part about getting the cell effect with rubbing alcohol. Is 91% alcohol okay? Thank you for writing this, and sharing information that most artists consider a “secret”!!

Thank you Kailey. We’ve always been of the opinion that giving information about techniques is a two way street; you get back as much as you give. I found both 70% and 91% alcohol works for this process. 91% might be better in terms of not having to add as much into the mixture. The alcohol should be mostly evaporated first in order to allow the acrylics to properly cure.

How long do fluid acrylics take to dry when used neat for pouring? I tired using these and they do not seem to dry……..

Any help will the appreciated

Regards, Joanna

Hello Joanna,

Acrylic paints applied heavy handedly can take several days to become solid and stable paints, and may require an additional several months to become fully dry. Much of this depends on the many factors about the drying of acrylics which we have an article about here: https://justpaint.org/investigating-the-drying-process-of-acrylic-color-and-gel-medium/

Interesting read, thank you for sharing this info.

I use equally challenging technique in terms of how to achive consistent results and the paint going down the drain (literarly). With this technique I create foam-like texture by applying narrow stream of water from a water sprayer on heavy body acrylic paint that’s been distributed onto a canvas.

I’m thinking if I should use mixture of water and acrylic medium instead of just water. Which medium would you recommend?

Hello Silvija,

There are probably many mediums which you can try for this technique. The GAC 100 or GAC 500 are the most likely candidates as they are thin, pure acrylic mediums. Rather than replace all of the water you use, you may be better served by blending water and medium (1:1 as a starting point) so that the technique produces the desired effects. However, if you do find adding medium for this part of the process not practical, you should then move to applying an “isolation coat” and then varnish to protect the work. Please let us know if you have any other comments. – Mike

Thank you for sharing the information.

I have the following question concerning the thickness of the poured layer, and the time between pouring the next layer.

Is the thickness of influence of the process letting the paint underneath rise ? In my experiment i poured a white layer directly on top of an black/blue layer, the white completely disappeared even with alcohol.

Hello Claudia. You are most welcome for the information. Poured painting layers are often quite thick, so you should allow ample time for the paint to coalesce before you apply the next layer. Usually, this can take between 3 and 7 days, depending on the overall factors such as temperature, humidity, air flow, product thickness and surface absorbency. I’m not sure what happened with your painting, not knowing all the details. It’s possible the density of the white caused it all to drop to the bottom of the blue/black, but the most dramatic effects would be to pour these layers immediately on top of one another. Hope that helps! If not, please contact me directly via email and we can figure out what’s going on.

Claudia why not try something I got great results from. I mixed pouring medium with fluid acrylics making a white a black and 2 other colors – no alcohol. I poured the white with my board at an angle then the black then the other colors. I then took a light weight paper color swats from Home Depot and lightly swiped a ross the paint. Then I let it sit and do its thing. I got some cells and spider webbing. Try it and hope you get great results like I did.

Great topic and excellent advise! Question : can I use my normal acrylic paint (brush and pallet knife) as I see you advise high flow acrylic. Can I turn my heavy body paint into high flow somehow ?

Thanks

Thank you Peter. In regards to modifying a thicker acrylic paint to be used in this process, it’s possible, but I have not tested it. You would want to first thin the paint down with a blend of water and medium (for example 3 parts water to 2 parts GAC 100). Add small amounts of this acrylic-water mixture into the paint until the paint becomes pourable, then it can be modified with the GAC 800 and isopropyl. As stated in the article there are many variables which influence the patterns developing, so you may need to adjust the ratios of products until you find the combination that provides the right movement of paint.

Yes, heavy body acrylics can definitely be thinned down for pouring and liquid painting. I have used it many times.

Thanks for your comment. What would ratio be since I expect you have to use more fluid additives (water, medium…).

Is your GAC 800 the equivalent of Liquitex pouring medium?

Hi Christine,

Thanks for your question. The GAC 800 can be used as an alternative for pouring when paints are added with it. The GAC 800 lacks the level of clarity of Liquitex Pouring Medium, so we do not suggest to use it as a topcoat or 2-part epoxy alternative. As you can see, when used with color, the GAC 800 allows you to pour with minimal concerns of “crazes”. – Mike Townsend

Is GAC100, GAC400 or GAC500 closer to the Liquitex pouring medium? What are the differences in all of these and GAC800?

Not really. They interact differently with the paints. Pouring medium tends to spread the colors a bit, GAC 800 does not. They both are quite good for pouring; you’ll just get some different effects. Each has its uses, and yes, they can be mixed. I would recommend, if using Liquitex Pouring medium, that you add something like a tiny bit of flow release, otherwise it can easily skin over. VERY easily skin over in the mixing cups. GAC 800 is a staple for my liquid paint/pouring mixtures. Both are excellent! As Mike says, you will have to experiment.

Plus a helpful money saving tip you can mix elmers glue and water into the paint plus silicon or oil until satisfyed with the consistency I found that it works even better than liqutex pouring medium if you have any questions or concerns please contact me.

Max, the use of Elmer’s Glue (a PVA material) can also have an impact on the durability of the paint film. As PVA ages, it becomes very stiff to the point of being brittle. This may not be an issue on panels but on canvas the movement could create cracking of the entire film. Artists are certainly free to do as they please with various additions of non-archival, untested paint mixtures, and achieve interesting effects, but there are no guarantees the resulting paint layers will hold up over time.

– Mike

Hi Michael, Question, what if I add a coat of resin over my pouring where I added Elmers glue? Do you think that could prevent my painting to create crazing over time?

Thannk you for this article!

Hello Ninozka.

You are very welcome for the article. I know there are artists using the Elmer’s Glue (PVA binder) and then using epoxy resin on top to finish, but since we do not make either of them, it would be critical to test them out on a non-important painting panel and see how they fare. Epoxy should not craze because it’s a two-component system that cures from chemical reaction and not water or solvent evaporation.

– Mike

Great help here with alcohol pours!!! but wondering if they could be made up & stored for a time? I am assuming the alcohol will evaporate if not kept in airtight containers.. Also does each color including the titanium contain the alcohol??

Thanks.

Hello Maureen,

I have made mixtures and kept them in a sealed jar, and they have worked. The alcohol as you mention does flash off very quickly, so if the container has a lot of head space it would fill with the alcohol, lessening the amount in the liquid paint mixture. Overall though we’d suggest creating these mixtures and using them fresh, as there isn’t any trials where we studied the affect of alcohol mixed with the paint long term, so it may end up wasting product. We just don’t know for sure. In the image from the article showing this effect, all of the colors were mixed approximately similar in regards to the ratios of paint, medium and isopropyl.

Hi Michael

This is a great article, it’s very difficult to find information on mixtures for the alcohol pouring technique. Do you have recommendations for the substrate to use, I’ve tried gesso covered canvas boards and the paints sink in and you see the canvas texture in certain areas. I also tried gesso covered wooden boxes and I had severe cracking.

I really want to achieve a smooth glass like finish, I realize I can pour epoxy resin to give it it’s final coat but I’m struggling to get the desired finish prior to this.

Thanks

Hi David,

Thank you for comments. If you seal the surface of the gesso with acrylic medium before doing the pours they will be much smoother. For example, the Soft Gel Gloss thinned 2:1 with water (isolation coat recipe used prior to applying varnish). Smoothing canvas with Molding Paste works really well also. The same thing is true with the wooden substrates, as gesso on wood is highly absorbent. I should note also that with all of alcohol evaporating from the paint layers the surface isn’t as smooth as it is when using just GAC 800 and paint. You could also apply pure GAC 800 as a thin coat but as the article mentions, it’s slightly hazy, so you have to make sure it’s not going to be an issue for your artwork.

Hi Michael, I really appreciated this article about pouring. Very clean and clear and understandable. There is also the pouring technique where you start by putting your canvas in water and you pour the colors directly on the canvas in the water and when you pour it out it makes beautiful effects and less messy. Did you try that method?

thank you very much.

Hello Linda,

Thank you for the kind words about my article. There are certainly many kinds of pourable paint applications we were not able to cover within this article. We refer to the technique you describe as “stain-painting”.

Here is a video that supports this painting approach: . Perhaps in another article we could speak to this technique! – Mike

I want to thank you so much for this article! I searched for hours and hours for this exact information! I have been trying over and over to achieve the “cellular pattern” look. I tried last night and it didn’t quite work the way it does in that picture but I took notes and I’m sure I just need to keep trying as you mentioned, “As with any new painting technique, do not be discouraged if the desired results don’t happen immediately.”

The way I did it was that I poured the paint, then dripped the alcohol onto it, but as i re-read the article, maybe I was supposed to mix it in with the paint?

Thank you again! This is so helpful 🙂

Hello Jennifer!

I’m very glad you found the article so useful. You are correct that you want to mix the alcohol in with the paint and medium, because it’s the action of the alcohol rising to the surface, pulling paint along with it, that causes the patterns to emerge. Keep at it! – Mike

I had tried with the golden high flow and fluid acrylic with rubbing alcohol but did not get the cellular effect. What went wrong ? Should the paints be mixed thoroughly with the alcohol before tilting the canvas. Any sequence on the pouring ?

Hello Jackson,

The way I have been mixing the paints up has been by mixing them in a tight sealing jar and shaking the mixture up. The air bubbles seem to help create the cellular patterns. The key though is to have one color flowing over others, wet into wet. So, mix the paints with the alcohol, pour one or more colors out and then tilt the canvas so that one color can roll over the other. – Mike

Thank you. Will try that again

how can I get the cells effect of Arthur Brouthers? Which medium can I use? Thank you

Hello Moni,

Thank you for your questions. I can only speak to what has been working for me, which is the isopropyl alcohol and GAC 800 with High Flow and Fluid Acrylics. How Arthur Brouthers specifically accomplishes his work is unknown to me.

Thank you for your information. Will try the alcohol and gac 800 combo with the fluid acrylics.

Probably some kind of silicone, judging from my experience. However, I am not Arthur Brouthers whose pours are fantastic!!!!…so maybe you can contact him? Or contact Annemarie Ridderhof. She knows a lot about acrylic pours too.

Moni, did you ever get any further in your research of Arthur Brouthers type mixture/technique? I am also on the hunt for finding out this information. If I do find out, I can post here. If you find out anything, or if anyone who sees this message knows the secrets to creating works like Arthur Brouthers, PLEASE 🙂 reply/post. Thank you.

Hello Dani,

I don’t know of the Arthur Brouthers specific techniques but I believe they use epoxy resin as their base.

There’s also some interesting reading about whom I believe is the originator of using hydrodynamic instability to create patterns: David Alfaro Siqueiros, who described the result as “accidental painting”.

– Mike

What a great article. Answered so many of my questions. Now I can proceed with confidence that my paintings will remain intact. Thank you

You are most welcome, Linda.

Hey Michael….i did a large canvas last night….it was perfect when i went to bed, but i woke to something completely different this morning! The paints moved SO much overnight and i really don’t like it anymore. Parts are now very think and tacky. Once it’s completely dry, can i re-pour/layer over the top?

Really need to salvage it!!

Hello Jenna. With the great patterns resulting from alcohol, it is important to not overdo the alcohol additions. They make the paint mixtures very thin and very volatile. Try reducing the amount you are adding so that the majority of alcohol has left the paint film before the film formation process begins. Also realize that dense pigments such as ultramarine blue will readily sink in a liquid paint layer, and if you are adding the levels of GAC 800 I did when crafting this article, the mixture becomes less milky and more transparent after it dries.

I love this techniques, always surprised by the results!

I’m interested in putting a second layer on top of the dry first layer. I’m hoping to lightly lift off the dry second layer to reveal the color underneath. Instead, both layers come off together. How can I get the result I want?

Thank you.

Hi Judy. Without seeing the work it’s difficult to understand what you are experiencing. However, it sounds as though the first layer was not completely dry, or it was perhaps overloaded with alcohol and that might make it more sensitive to a second application. You may need to apply an isolation coat of acrylic medium before you attempt another layer with alcohol in it.

hi! just wondering, when you mix alcohol into paints to get more cells, is this when you pour the paint on the canvas in a water bath/dip the paints into a water bath or do you only mix alcohol into the paint when you are doing a dry fluid paint? not sure if i’m describing it correctly–im entirely new and only started researching this yesterday and i watched alot of youtube where canvases were either in water or dipped in water. thanks!! I love the cell look.

Hi Elizabeth. Thanks for commenting. No, you are describing a marbling technique, which is quite different. That technique involves hydrophobic paints (usually enamels or oils) that readily float on water, and an object is pushed through which imprints a pattern onto the surface. It can be done with acrylics although thickened water is best for waterbased paints.

This article was super helpful. Thank you.

You are very welcome!

Do you have/will you make a demo video of this technique?

Hello Li,

No video just yet showing the application just yet. What would you like to see in the video that would be most helpful for you?

I guess just watching the amounts of each to use in the timing …

Did you ever get around to making that video about creating cells in poured painting?

Hello Suni,

Thanks for your question.

I don’t have a timetable for when videos on pouring will be release but we are currently filming.

– Mike

Hello, Michael.

Thank you so much for this informative article. I have been practicing the acrylic pouring technique for a few months, and my biggest obstacle has been little to not-so-little craters created by air bubbles that popped while the paint was drying. Is there anything you could suggest that would prevent this besides sitting in front of your piece for hours popping every single bubble you see? You mentioned in the article to let your paint mixture sit overnight in a container before pouring. Is that the best method to prevent air bubbles? Would mixing the alcohol into mixture prevent this as well? Thanks so much in advance!

Hi Sarah,

You are most welcome for the article. When I started out doing pouring my impatience to work definitely led to many unwanted bubbles and craters. It is nearly impossible to mix paints and mediums together without developing air bubbles, but as you cited, the best approach to removing them is to simply allow the mixtures to sit overnight. Pre-mixing batches allows you to dial in the color and have it ready to use for the near future. Some mixtures may have the denser pigments settling a bit while in storage, but often just a gentle stirring returns the mixture to a uniform color. While adding some alcohol might help the mixing bubbles rise and pop faster, it’s not a great substitute for time.

Hi Sarah, try torching your painting once you have poured the paint. I use a creme bruille torch that chefs use to caramelize sugar on top of deserts. Lightly wave the flame over the painting fairly quickly at a distance of approximately 5 or 6 inches above your painting. This will pop the bubbles and enable the alcohol to form cells more quickly. This is a technique also used in resin pours. Hope this is if some help to you.

This technique could be dangerous with alcohol. Very flammable. The torch is normally used on silicon/paint mixtures to create cells.

Thanks Susan. That’s a great point. – Mike

Thank you Michael

I use a product called Flowtrol there are several companies that make it but the one I have is made by Flood and is purchased from a paint supply store.

Hello Deborah,

Flood’s Floetrol is the only one I have seen. Floetrol is a paint modifier, designed to improve spraying, rolling and brushing out of housepaints. In testing, I have noted that it greatly lowers the gloss of the paint mixture. Flood suggests adding no more than 25% into any mixture, but only “approximately 8 oz. (237 mL) per gallon (3.78 Liters) of paint. If paint is thick, or in extremetemperatures, more FLOETROL may be gradually added, up to 16 oz. (473 mL) per gallon (3.78 Liters)”.

– Mike

This is great info thank you so much! Just one question how many layers do you suggest be poured before rolling the canvas around to completely cover it with paint?

Hello Serena,

Thank you for your feedback. I think that the number of layers depends on how complicated of a design you want to have. I could see this effect work with just two colors. You could pour a color on half of the canvas and then cover the other half with the next color, or you could completely cover the surface with one color and then add the next over it. In this case, I like to have a light pigment color applied first, and then a denser color over top. For example, Quinacridone Red as the base and then Titanium White on top.

Michael Townsend

Hello is there a French translation please. I would like to try this. Thanks for your answer. Nicole

Hello Nicole, This article has not been translated, but you can copy the text and run it through a translator program, such as Babblefish.

Like This: Bonjour Nicole, Cet article n’a pas été traduit, mais vous pouvez copier le texte et le lancer à travers un programme de traducteur, comme Babblefish.

Please let us know if something does not translate well for you.

Michael Townsend

Thank you, Michael for this article! Is it absolutely necessary that the canvas be gessoed or can you use a “raw” canvas to create a nice piece using GAC800, alcohol, and acrylic. Thanks again.

Thank you for the information Michael. One question please, have you experimented with both a gessoed and raw canvas? Is it absolutely necessary to prime the canvas before you pour? Thank you!

Hello Adelina.

You are most welcome for the article. You do not need to gesso the canvas necessarily, however, in my experience you will likely lose a great deal of the detail due to the canvas weave.

Hi,

Ive recently started doing pours however I’m really struggling with it drying evenly. I level out my canvas at the beginning and then once in finished I come back in about an hours time and then for some reason there is a thick layer of paint that hasnt reached an edge causing it to clump. Is there any possible way to fix this?

Hello Veronica.

I’m having difficulty understanding what you are experiencing. Please contact me directly, with images if possible of what the issue is, and what products and ratios you have tried thus far. [email protected]

– Mike Townsend

Hi. Is it possible to use normal craft paint from Walmart for this method? If I just properly thin it out with water and Liquitex Medium?

Hello R. It may be possible, but we have not tested using other brands of products.

You can use cheap paint and also house paint.

Deborah,

Yes, you can use cheap paint and housepaint, but realize these products are made with lower quality colorants and binders, both of which can result in long term permanency issues.

– Mike

Hello! Thank you for this article 🙂 I’m having problems with the finished edges of my pour paintings. I’m wiping them but generally as it dries I get more drips which creates ridges or lumps, sometimes a bubble….and then i get some parts that didn’t get any paint. I’m using a pouring medium with different types of paints in it and I LOVE the results I’m getting I just can’t get the sides looking well enough. Any suggestions? The pouring medium makes it dry with a plasticy type of feel so unless I sanded them down I can’t really get rid of the drips, maybe just paint over them with a neutral color?

Thank you!

Hello Dawn,

Thank you for contacting us with your questions. Pre-painting the canvas and edges is a good idea before doing the actual pours. Then tape off the edges well. If the pours flowing over the edge are thin enough they should pull away fairly cleanly, although it’s not uncommon you will also need to slice some of the thicker areas with a razor knife. You can also apply a second tape along the edges using a less adhesive tape (for example masking tape is used for the initial tape and painters blue tape is used for the second). Once you are done with the pouring, allow the paint to level and stop flowing, then while wet, pull the low adhesive tape off but leave the underlying tape in place until everything is completely dry.

– Mike

Hello Michael.

Thank you for sharing such great tips for pouring paint. I have been wanting to try this for very long but never had the right information about the ratios in which to mix the paint.

Just a quick question. Do I need to seal the painting after it has dries completely? If yes, then what do you suggest I do it with?

Thank you so much.

You are most welcome, Veda.

Heavy-handed applications like these pours will take some time to really dry. My suggestion would be to wait for at least a week if you can before moving onto any additional layers, including varnishing. Acrylics are quite durable and do not necessarily require a varnish, but it can adjust the sheen and add some depth (especially gloss coats). Overall though, varnish is intended for the long haul and may be applied at any point in time. The GOLDEN Polymer Varnish, MSA Varnish and Archival Varnish are compatible with acrylic paintings.

Michael

Hi Michael! I was curious with example #2 if there needed to be a drying period between different colors or if you could pour one after another!

Thank you so much for this article, it cleared up a lot of questions for me that I’ve been researching for a long time.

Hello Jenna,

You are most welcome for the information. I’m glad it helps with your own artwork. For the image #2 work, the paints were premixed and allowed to sit in a sealed container. After at least overnight, the paints were then poured onto one central spot and the liquid mixture flows outward. There was a box on top of the panel that the paint flowed over and that resulted in the line between the rings.

Michael

Great article! I have been like a mad scientist in my painting room for hours experimenting! I have had some amazing results with the water and alcohol mix. In order to get the look I want, I mix each paint at different dilutions. The problem I’m having is, because some colors are much thinner, it’s moving too much. I get an awesome image and then it keeps moving and turns to mud. This may be a crazy question but is there anything at all to add to the paint, or spray on the paint once the look is achieved to stop the movement?? If I thicken the paints, I just don’t get the effect I want. Thank you!

Thank you Tracy. There’s no magical spray to freeze a pattern, but overadding alcohol causes more movement and change until it’s evaporated from the paint layer. Thicker mixtures with just enough alcohol to create the cellular patterning seem to be the most stable.

great article.. was in doubt if we can also use Medium1 which is used for transperency and water colour effect instead of the poring medim?

I’m sure there are many types of paints and mediums that can be used for this effect, but we have not currently tested them. I will say that thinner mixtures will create patterns but they usually change rapidly until they are dry. Thicker products tend to “settle down” faster, especially if the alcohol isn’t over-added.

– Mike

Hi Michael,

I have been experimenting with the densities of paint for some time. You state that the opaque high flow colors are better than transparent ones. You also said that using Titanium White ( a dense paint) on top allows the most aggressive colors to pop through.

Are there any charts on the densities of the various High Flow colors? What makes a color, like Ultramarine Blue, more aggressive?

Thanks for any help you can give me!!

Julie Underriner

Hello Julie,

Thanks for contacting us with your questions. Very recently we published a listing of the density of the pigments used in our paints, available here: http://www.goldenpaints.com/pdf_viewer?file=http://goldenhub.goldenpaints.com/storage/uploads/pigment-density-of-golden-artist-colors.pdf. Titanium White usually gives good patterning, and when used over lighter colors that contain alcohol, the cellular patterns push through the white and rise, while the white is displaced and begins to sink. Less dense pigments should rise more readily than denser ones, and the difference helps interesting effects develop. Pigment is only part of the equation, as every paint color, every paint line will influence the way the patterns develop. Unfortunately, these differences fall under our trade secrecy and I am not at liberty to disclose them. I would as always encourage to conduct testing, as similar paints should have similar formulas, such as the Phthalo or Quinacridone families.

Mike

Hi Mike–Ive read this entire thread (!!), and am awed by your kindness at replying to EVERY.SINGLE.COMMENT!

Is there a way to test the density of paints, that aren’t Golden? I LOVE the pigment density chart you have, and use it readily, and sort of approximate pigments with other brands. I didn’t know if there was a better way to try and figure that out?

Thanks so much!

Dawn

Thanks Dawn! I greatly appreciate the comments. The paint pigment density list is universal, so any brand of paint that uses that specific pigment should have similar density levels. When paints are made from blended pigments that is when it becomes complex. Most companies are less willing to provide specific ratios and some do not list the pigments they use.

I hope that helps out!

– Mike

Hi Michael,

When I click on the link to the density chart, I get this message:

PDF.js v1.2.109 (build: 875588d)

Message: Unexpected server response (0) while retrieving PDF “http://goldenhub.goldenpaints.com/storage/uploads/pigment-density-of-golden-artist-colors.pdf”.

I also can’t find it looking through all of the articles on the website. Can you send me a link to the density chart?

Thanks,

Kelly

Kelly _ I had the same problem . When I went to the Golden site I typed “density of Pigments” into the search box and got the PDF to download to my computer. All the information was there when I opened it. Hope that will work for you too.

I get Sorry page not found of that link.

Hello, Kristin. Which link are you referring to? – Mike

Hi Michael:

I have a different project in mind. Most of your responders seek a mirror-like surface. I, on the other hand, wish to achieve a rippled surface. I am a model-railroader and have been preparing a dry river bed. I have applied earth colored paints to my medium surface and now wish to apply acrylic to achieve a rippled, glossy surface indicating the movement of water along the river-bed. Can you suggest a technique that would help create the idea of flow around boulders and islands in my river channel? Would use of a thin knife blade or a needle to create lines suggesting flow be possible just before the surface begins to skin over or would the time-line be too brief to accomplish the pour and the subsequent rippling effect? My river surface averages about ten inches wide and extends approximately five feet.

Hello Don,

There are some ways you can try out to create textural crazing in acrylic products and some others that can allow you to have a control in how to adjust the width of the craze. First, as mentioned in the article, crazes develop when the surface skins before the underlying materials have begun to dry. This seeds the surface and starts the patterning. Our experience with products containing fillers and aggregates that also craze are somewhat limited but it does happen. Products like Coarse Pumice Gel, Molding Paste, and various earth colors (ochres, umbers, oxides, etc.) can be blended and reduced with some water. You may also find that using dry solids in the mixture will help as well. The amount of acrylic binder needs to be low to help encourage the “failure”. The mixtures can be applied heavy handed, and then you would want to use heat lamps and fans to get the surface to become touch dry. You might find it better to then leave the lamp and fans on, or you might find that once the surface is dry it helps to then turn them off so they can dry slowly and maximize the effect.

In terms of being able to control the width of the craze, that can be even more unpredictable, but if you apply the products onto a polyethylene plastic sheeting (4 mil poly plastic sheeting from the hardware store secured well to a wooden surface) you can allow it all to dry first, and then peel the acrylics from the surface of the plastic and use gel to attach them to the model surface.

Modelers in the past have used thick gels to create the ripples of the moving water using a palette knife to model the ripples and waves. You may want to start with a shallow overall layer of gel (Soft Gel Gloss or Regular Gel Gloss) and after that dries, use Regular Gel or Heavy Gel to selectively create the ripples. You can mix a little Titanium White into the gel for white water effects. Others have used products like our Clear Granular Gel and Glass Bead Gel to simulate air bubbles, or simply frothed up the thicker gels first, then applied them.

I hope this helps out. Please contact the Material Specialists directly at [email protected] if you require any more information about these applications.

– Mike

I currently shaped my own surfboard this past summer and have been dying to try something like this on my board. Do you think the foam would absorb the paint too much and the effect would not work? Thanks!

Hello Maddisen,

You may want to apply a sealer coat of medium or paint onto the board foam first, then do the poured techniques after the initial layers have had time to dry well. We would also suggest testing the foam to see if any of the ingredients (such as the isopropyl alcohol if used) will interact negatively with the foam.

– Mike

Hello, I see artists using oil (silicon) to create cells in their acrylic pours. Would any others oils have a similar or better even, a different effect ?

Hello Peter,

Thank you for your questions. The use of silicone oils has become a popular trend for producing cellular patters in poured acrylics. The concerns we have for doing this stem from what the ramifications of these oils remaining in the paint film. Some of the oils never dry, others leave residue behind, and some evaporate completely. Applying several drops of the oil onto a sheet of clean smooth glass and observing their drying is very important, as these products were not created with the intent to mix with acrylics. They may be just fine, but if they don’t dry or leave a residue, can they be varnished or otherwise topcoated with other acrylics? We just do not have the testing to support this. With isopropyl alcohol, at least we know it completely leaves the paint film early on, and therefore creates patterns without lingering additives being left behind. Experiments and repeating successful applications before incorporating them into your actual artwork is highly suggested!

– Mike

Mike,

Thanks for your quick reply! Does IPA create cells as well or only the webbing in the paint ?

Would you put it in all colours used or just pick some out ?

If I see the result some pro’s have I ask myself if this can be achieve in one pour. Do you have any experience in ‘multilayer’ pouring ? If so how does that go ?

Thx

The range of patterns with the alcohol allow for cells to form. I just posted a link for a density chart which should help to offer a bit more control for colors patterning.

Thank you so much for this college crash course in acrylic pouring. Per your reference listing of paints, are the paints with a lower specific gravity the ones that form the nicest large cells when using alcohol and layering?

Thank you in advance.

Joyce

You are most welcome Joyce.

The use of the pigment density chart is to create contrasts of both the pigment density of paints used. For example, a low density pigment like Diarylide Yellow mixed with some isopropyl alcohol and GAC 800 will naturally want to rise out and push open a higher density pigment such as Titanium White. As the white opens up to allow the alcohol to escape, the yellow is revealed. As this happens, you’ll see many You Tube artists tilting the paintings to stretch the cells open even more.

– Mike

IF you want to use an oil type product to produce cells and take your chances, silicone is the best choice, IMO. Mineral oils do not have the same effects and I would trust any drying oils way less than either silicone and/or dimethicone.

NOTE: We recently published a list of our pigment densities. It should prove very handy for artists who pour: Here’s the Article.

Very handy. Thanks a lot! Is this top science or could I also determine this as well for all the paints and brands I have lying around my studio ? Is their a DIY method ?

You are most welcome Peter.

As far as I know, the isopropyl alcohol additions should work with various products, although I can only directly speak to the materials I have tried. The mixtures need to be thin enough to flow and move and in turn allow the alcohol to rise and spread the paint into the patterns. Start with small 1 ounce mixtures and keep track of the general percentages of each component. Also, try using a couple of paints with different pigments. In other words, don’t use paints that all have Titanium White in them, but some organics and inorganics, with tinted white paints.

– Mike

Mike,

Great article, thanks much! I was curious as to how I may keep the vibrancy of the colors while pouring. I had an amazing piece (5 or 6 colors) that looked amazing…until it dried. This left the piece looking very dark, grim, and muddy. It still looks neat, but I was curious if there is something I could be doing to keep that color popping and the colors from blending so much.. rather than darken/muddy? Thanks again!! Cheers.

Hello Michael,

You’re welcome for the information. There are a couple of things I believe you are referring to which I can help with. The best approach for me is to add just enough isopropyl alcohol to achieve the effect and then leave the paint film. If there is a lot of alcohol added it looks amazing when wet and moving but the mixture is so thin that the paints keep moving and blending which contributes to the muddiness.

Another key factor is that there is considerable color shift from wet to dry. The wet acrylic binder is milky and the colors tend to be tinted as if white was added. As the acrylic dries and clears, the colors can return to become much darker. Over a white and black stripe, pour a little of the mixture and let it dry. This will tell you what to expect. Try using more opaque colors and even a little Titanium White to improve opacity as needed.

I hope that helps!

– Mike

There is a sweet spot for dirty pours regarding paint consistency. Too thin, colors blend, too thick, virtually no blending at all, and very small cells whatever method is being used. Brilliant pours CAN be done. You just have to find that sweet spot. And, as Mike says, add a bit of white to the more transparent colors. It will help a LOT.

Thank you for all the great information! I love the colors in the last image, specifically on the right side, the turquois with the red and rust over the top. Could you tell me what paints were used to make the image?

Also the pigment densities list is very helpful but missing some colors, specifically turquois (phthalo), bronze, and sepia. I know these are multiple pigments, and I’m wondering how to predict the density of these colors.

Hello Victoria, you are most welcome!

Colors used in Image 3’s pour would be: Quin Burnt Orange, Teal, Phthalo Blue, Napthol Red Dark, Hansa Yellow Light and Phthalo Green Blue Yellow Shade.

The pigment density list is about the individual pigments not the actual paints. The paint density delves into trade secrecy information. However, for paints that are mixtures I would use the main pigment’s density as the one to test around. For example the Teal is comprised of Titanium White, Phthalo Blue and Phthalo Green with Titanium White being the main color used it seems to also be the main contributor to the patterning.

I have taken my Golden liquid acrylics and marked their density number with a sharpie on the lid. That really helps me when I’m choosing my colors. Just a trick to make it easier!!

Hello Shelly. That’s a great idea and should make it easier when you are mixing products!

– Mike

Hi Michael. Thank you for this excellent article!

What would you recommend as an archival way of varnishing poured acrylic while minimizing brushstrokes?

Right now, I’m using gamvar, which is archival and clear, but the surface film remains quite delicate and vulnerable to damage (ferrotyping, dents, etc.) when the art is stored or shipped.

Hi Kirsten,

You are very welcome! Spraying the varnish is the best way to apply and not have brush strokes or trapped bubbles. If your artwork is under 3’x3′ you can use the GOLDEN Archival Spray Varnish. Apply one or more coats until you achieve a uniform surface. contact us if you have any questions at [email protected]. – Mike

Hi , thanks for the awesome article , it’s very informative and found it very useful . I recently started painting with high flow acrylics and attempting to do fluid painting – at the moment I just use acrylic paint, high flow acrylics and a pouring medium – I get cells but not too many .

Just wondering if to add alcohol to all colours or just 1 or 2?

Thank you !

Hi Romy,

You are welcome! You don’t have to mix the alcohol into every color, but it might help as you are learning. If you don’t get enough cells after you pour the mixtures out, use a palette knife to nudge the product a bit, and fold a color over another and see if that helps to encourage the pattern. – Mike

Ok So I’ve done pouring but want to try the alcohol step. I understand the mixing but do I add this mixture “as a pour” or do I do it such as like droplets onto the already poured painting?

I have had the most success from mixing the alcohol with the paints, not onto the surface. I have seen spraying onto the surface create some interesting effects but the best cell patterns have come from mixing with the paint. – Mike

Hi Michael,

There is a lot of activity on YOUTUBE mixing a few drops of Silicone Oil into Fluid Acrylics, then heating the surface with a Culinary Torch to create ‘cells’. I’m thinking that this has got to be toxic! Any thoughts on health impact. Not much of any info online. I’m teaching a course on Acrylic Pours and I know there will be interest from the students because of the popularity of this approach on social media.

Thanks in advance,

Tina

Hello Tina,

Thank you for you comments. Although silicone is used with high temperatures in baking (think of silicone impregnated parchment papers, for example) the heat could in fact be causing outgassing of the acrylic resins and paint additives, and these materials are not FDA approved. In most of the videos, the torch is used to coax out the silicone to create patterns, but artists should be taking the proper precautions when trying applications like this. Good ventilation, organic vapor respirators and use of personal protective gear is highly encouraged. – Mike Townsend

Is the ventilation / respirator necessary if one is not torching (i.e., using pouring medium, silicone, maybe alcohol), but hot heating)? And I guess–if the rest is safe–then if one did want to torch, the precautions would apply not only during, but for some length of time thereafter; any idea how long? (Please let me know if I should address my question directly to Golden.) Thank you! (Sorry if this is duplicate; I got error message re the Captcha code.)

Hello Grace.

For larger works, it’s always a good idea to think about ventilation. Air exchange can be as simple as leaving interior doors to the studio open, or using box fans exhausting out of a window. Acrylic gives off ammonia which should be limited. Isopropyl alcohol is not great to inhale in large amounts either. I do not know any concerns of silicone as it escapes a paint film but there are many forms of silicone oils and solvents, so check with the kind you are working with, such as dimethicone. Torching acrylics and other painting products come with a lot of unknowns. Being plastic, if they are heated excessively they will begin to give off toxic fumes.

– Mike Townsend

Hi, I am a visual artist and I REALLY want to attempt this. Do you put the acrylic down first or put the alcohol first.

Hi Renee,

Thank you for your questions. Please read the article in detail to understand how I have been successful. Each artist needs to experiment to discover the techniques and product mixtures that work best for their needs. – Mike Townsend

Hello Michael

Just wanted to say thank you for such an informative article and your attentiveness to answering questions and comments. I have not yet taken the leap into pours but I have been fascinated watching the process and have been relishing the day I begin to commit to the many ideas swirling in my head.

You are most welcome Carmela. The best approach is to just get some small test surfaces, paints and mediums and give it a try. Take notes on what works and what doesn’t. Let us know if you have any questions.

Mike

I have also learned that I can thin down titanium white with floetrol and rubbing alcohol…you can add alcohol ink white snow to the mix for better effects.. Really thin spread over painting with a tounge depressor and spread it out. It laces nice over problem areas

Hi Shelly,

Thanks for your comments.

I have not tried mixing alcohol inks with the acrylic products, but it’s worth trying out and see what happens in a couple of experiments!

– Mike

Love the advice. Have you ever tried pouring onto rusty metal versus a canvas or panel? Just curious.

Thanks,

Mike

Hi Mike,

I have not tried pours on a rusty metal surface, but you might want to seal the rusty surface with a clear primer/sealer so that it doesn’t change when you apply waterborne products over it. Unless of course you want to encourage the rust to migrate into the wet layers.

– Mike

Is it possible to do this technique on a ceramic tile?

Hi Kelly,

Thanks for your question. There are commercially available “bonding primers” designed for use on tile and glass. XIM is one brand of such products. Just be sure the primer is suitable for “latex based paints” and it should also work for acrylic paints and mediums.

– Mike

Thanks for your insight Mr. Towsend…

Could you please tell us exactly how were the paints poured into the substrate to get that beautiful effect in image #2 ?

Thanks in advance,

Romano

Hello Romano,

Thank you for your comments and question. Image #2 is made using a mixture of GAC 800 and GOLDEN Fluid Acrylics, approximately at a 10 parts GAC 800 to 1 part paint ratio. Mix them together and allow them to sit in a sealed container overnight so that the air bubbles generated during mixing are able to rise up and pop. Then you can use them as desired. This image is made by pouring several colors in one location, until you create a bullseye series of rings. The pour may then be manipulated by slowly running a skinny stick or similar stylus through the rings.

– Mike

Hi Michael!

Thank you so much for posting this, it’s been incredibly helpful! Lately my colors have been getting supper muddled when I pour them, as in the colors become too mixed together and extremely dull when they dry, which leaves me with a really unappealing end product. I use pouring medium and a single cup for all my colors when I pour, but I’m not sure why the colors are turning out so poorly! Do you have any ideas? Thank you so much!

Hi Sarah!

You are welcome for the information. Without knowing the colors you are using and the paint line, it’s hard to say for certain what is causing the muddiness, but perhaps you might want to stick to an analogous set of colors (such as yellow, orange, red) and do not overmix the colors in the cup before you pour. The dull surface could be from the kinds of paints used. Pouring mediums tend to be glossy, so perhaps add less paint or switch to paints that do not have matting additives. GOLDEN Fluid Acrylics with GAC 800 should dry in the gloss to semigloss range.

– Mike

Outstanding article, and incredible patience to answer everyone’s questions and address each comment, thank you Michael! I definitely fall into the, “spent many frustrating nights in their studio figuring out the best application method that provides the desired results” category…I thought I nailed it, just last night. Gorgeous crisp separation, rich vibrancy, beautiful cell formation,-only to wake up to a muddy uninteresting mess this morning. (Level surface, tight canvas. PVA with water, paint, and added silicone.) Rats. Weeks now, after gathering a culmination of techniques and experimenting with a slew of different pouring mediums, paints, surfaces, ratios, and ‘cell coaxers’ I’m going to get it right eventually. Fine tune variables.Thank you for letting us know that silicones in pours may not stand the test of time-it didn’t occur to me until you explained why. Now I’m going to try isopropyl alcohol and get ‘sciency’ with specific gravities/densities of paints and see what results I can get. I appreciate all of the tips, and trouble shooting. Back to the lab, Erica.

Great to hear the information was useful, Erica!

– Mike

What formula do you use with fluid acrylics (you gave a formula for high flow, GAC 800 and isopropyl alcohol). Is it the same formula?

Hello Pat,

Yes, you can interchange the High FLow Acrylics and Fluid Acrylics as needed. Fluids and GAC 800 result in a thicker pour which seems to have more control. The thinner the pour the more dynamic the cell patterns can be, but they need to also be applied thinly or they will keep changing and morphing past what you wanted (or at least where you stopped with pouring and manipulation).

– Mike

Thank you Michael!

Thank you so much for this wonderful article. I’d just like to double-check my understanding of the recipe using fluid acrylics + GAC 800 + alcohol. Is it really the same ratio as for the high flow acrylics? That is, 2 parts GAC 800, to 1 part Fluid Acrylic paint, to 1 part 70% alcohol? I’m just hesitant, because when not adding alcohol, the ratio is 10 parts GAC 800 to 1 part Fluid Acrylics. Also, I’m weighing things (e.g., 20g GAC 800 + 10g Fluid Acrylic paint + 10g alcohol). It seems way more runny than expected. Do you have any input on that? How much alcohol is really needed to create cells? Thanks!

Hello Lee.

Thank you for your kind words and your questions. The starting ratio I currently prefer to use is 10 parts (not 2 parts) GAC 800, then 1 part GOLDEN Fluid Acrylics or High Flow Acrylics, and 1 part 91% isopropyl alcohol. I think your mixture would be much to thin for my taste, and sounds like that’s true for you also. By the way, you can also wait until the end of the pouring process and mist on droplets of alcohol instead of actually mixing them in with the paints.

– Mike Townsend

Hello Lee.

Thank you for your kind words and questions. The starting recipe should be more in line with 10:1:1, not 2:1:1. You can also leave out the alcohol in the paint mixture and spritz some on towards the end of the process.

– Mike Townsend