If a single color embodies the dividing line between pigments considered suitable for permanent works of art, and those that are suspect and poor in lightfastness, Alizarin Crimson (PR 83) would be it. And yet it is still used by many artists who are drawn to it in spite of its many problems. Some of that is driven by tradition, habit, and a sense of something special and unique about its color; a feeling that it exudes a natural earthiness and that more permanent substitutes can often appear too ‘clean’, or too high chroma, to be a perfect replacement. All of that is partly true and are among the reasons we still offer it in our line of Williamsburg Handmade Oil Colors. But the truth also persists that it has a marginal Lightfastness rating of ASTM III, or Fair, and that using it – especially in tints or glazes – runs a real risk of fading. Just how dramatic that can appear, and what might be done to help, is the topic we want to look at briefly.

If you are not familiar with how Lightfastness is measured, we would encourage you to first read our short Just Paint article on “Delta E: A Key to Understanding Lightfastness Readings”. However, while that explains how changes are measured and how those line up with ASTM Lightfastness categories, a few additional points will help make the test results clearer. The first and more surprising for many people is that lightfastness for artist colors are always based on how a pigment performs as a tint, in the case of oils or acrylics, or as a light wash for watercolors. The performance of a full-strength mass tone is never taken into account when following the various ASTM Standards for artist materials, such as D4302 for Oils, D5098 for Acrylics, and D5067 for Watercolors. However, it is something we always choose to include as it can offer additional insights about a color’s durability.

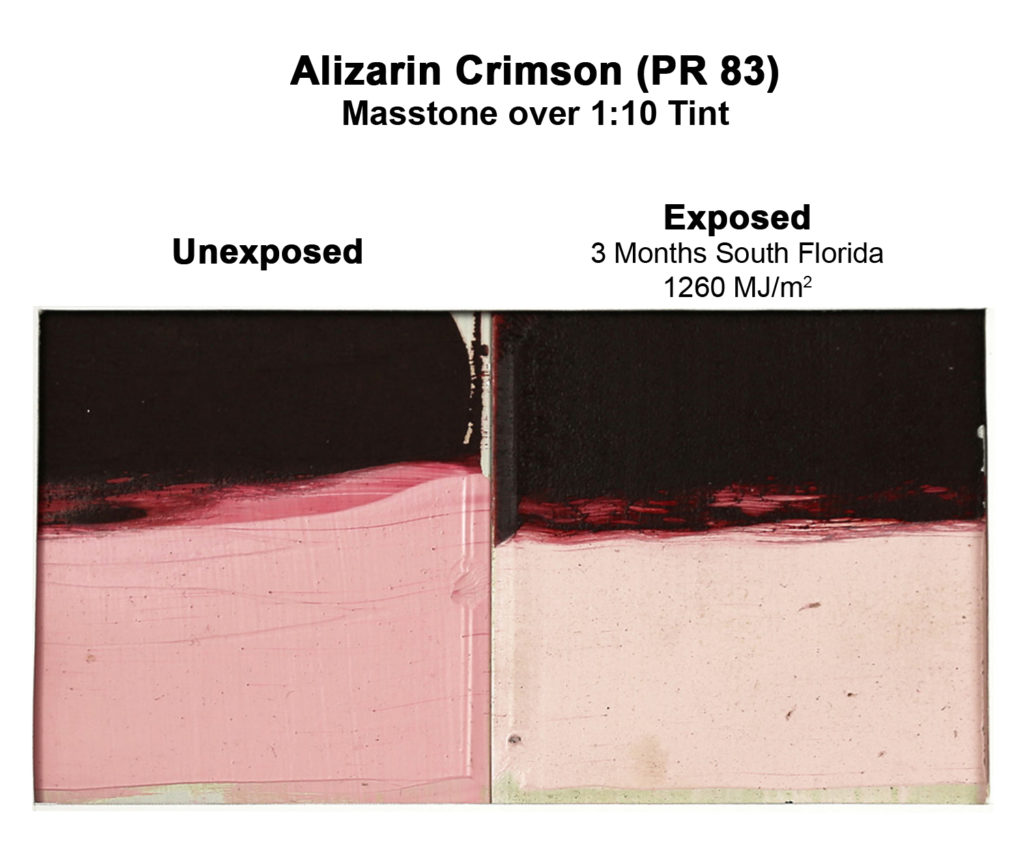

For example, in Image 1, you can see the results for Alizarin Crimson in oils, in both mass tone and 1:10 tint, after three months of outdoor exposure in South Florida, which approximates the amount of fading you can expect in roughly 100 years of museum-lit conditions. While the tint exhibits major fading, with a Delta E of 13.72 (well within ASTM III range), the mass tone actually does quite well. This goes to show that Alizarin Crimson, at least within oils, can actually perform in a very acceptable way when used full-strength, with test results showing a Delta E of 5.72, or the equivalence of a strong ASTM II Lightfastness rating.

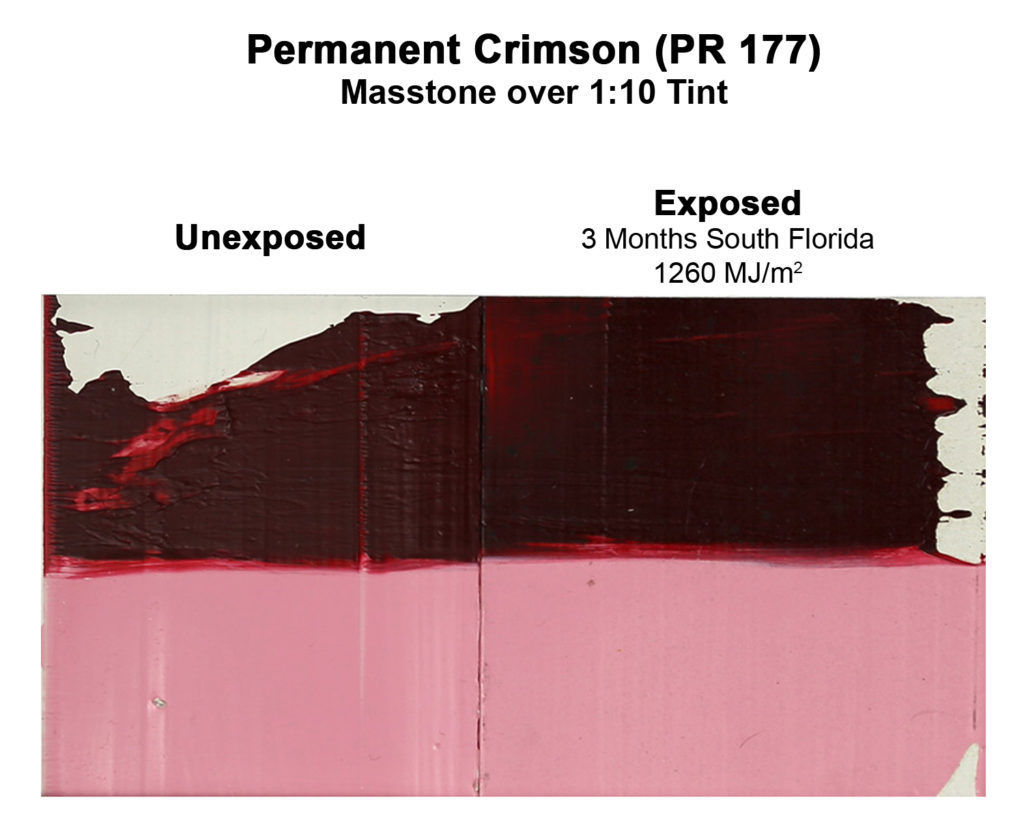

However, if needing to use the color in tints, glazes, or as a small component in a blend, or if simply wanting to work with the most lightfast choices, it may be better to use our Permanent Crimson (PR 177), seen in Image 2. A modern synthetic anthraquinone pigment, it creates richer, cleaner pinks and purples, while being rock solid in lightfastness, with the tint displaying a change of just 1.31 Delta E – the equivalent to a very solid rating of ASTM Lightfastness I, or Excellent. If needing to tone down the resulting color to more closely match the traditional Alizarin Crimson, adding a whisper of Phthalo Green can be helpful.

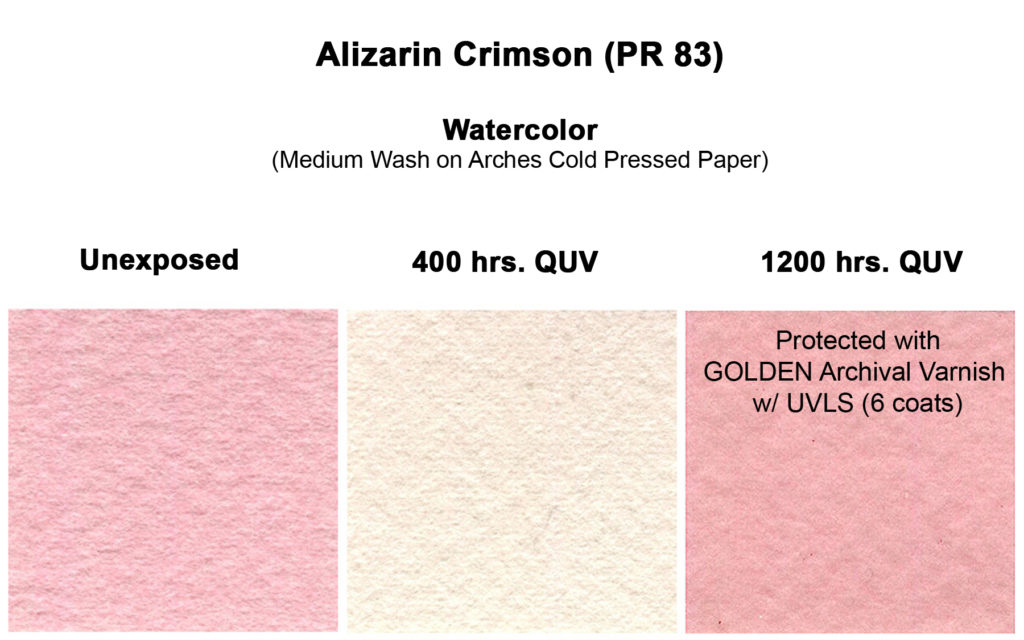

In watercolors Alizarin Crimson is even more vulnerable since the pigments are not encased in a binder and lay scattered over the surface of the paper, leaving them more exposed to UV and light in general, not to mention environmental conditions. To show just how dramatic the fading can be, we have chosen to display the results of a moderate wash, which is deeper and more pigmented than the much lighter wash called for in the lightfastness section of ASTM’s D5067. As you can see in Image 3, even this more substantial wash turned nearly completely white after just 400 hrs in a QUV Chamber, which roughly simulates the amount of fading one would expect after 33 yrs of museum-lit exposure. But there is also some good news. The third swatch shows results when the wash of Alizarin Crimson was protected by 6 sprayed coats of our Archival Varnish with UVLS, to see just how effective the protection might be, and we were pleased to see that after 1200 hrs of exposure – or the rough equivalent of 100 years of museum-lit conditions – the color held up fairly well, with a Delta E of just around 2.0, or the equivalence of ASTM I, Excellent. However, this degree of protection also comes at a cost, as the sense of the uncoated, delicate paper surface was lost and the color was clearly altered in the process.

So where does this leave us? More testing is definitely needed to fully understand how effective UV filtering varnishes might be for lighter tints and glazes of Alizarin Crimson in oils and other media, and we should remember that accelerated testing is never a guarantee that these will be the actual results in the real world since the variables are simply too vast to duplicate. Until then, this venerable and historic color should be used with great caution and with the full understanding that it is vulnerable to fading and is considered by nearly every expert in art materials and conservation as having poor lightfastness, and could even be considered highly fugitive depending on how it is used. If you do use this color, keep it as strong in tone as possible, limit its use in glazes and tints, and by all means when possible either varnish the piece with a UV filtering varnish or mount it behind a museum-grade UV filtering glass or acrylic sheet.