Working with the conservation community we undertook research in conservation issues of acrylic paints and paintings, desiring a formal understanding of something most acrylic painters might take for granted: That if an acrylic painting gets dirty, it can simply be washed off with a damp rag. Just to be clear, we are not currently recommending this practice. Just Paint 5 took a look at conservation cleaning methods currently recommended for acrylic paint surfaces. These remain quite conservative and appropriate for conservators. We have tried to examine more aggressive cleaning techniques that might be practiced by artists and to simply characterize the sort of changes that might occur. Our results showed that under certain conditions and with certain pigments, washing did not show any visible damage. Future research will investigate more precise conditions, the level of changes that may occur in certain colors or mediums and if, in fact, washing may improve the surface by removing surfactants from the paint surface.

Working with the conservation community we undertook research in conservation issues of acrylic paints and paintings, desiring a formal understanding of something most acrylic painters might take for granted: That if an acrylic painting gets dirty, it can simply be washed off with a damp rag. Just to be clear, we are not currently recommending this practice. Just Paint 5 took a look at conservation cleaning methods currently recommended for acrylic paint surfaces. These remain quite conservative and appropriate for conservators. We have tried to examine more aggressive cleaning techniques that might be practiced by artists and to simply characterize the sort of changes that might occur. Our results showed that under certain conditions and with certain pigments, washing did not show any visible damage. Future research will investigate more precise conditions, the level of changes that may occur in certain colors or mediums and if, in fact, washing may improve the surface by removing surfactants from the paint surface.

Historical Review

To secure their rightful position in the historical pantheon of art materials, acrylics must undergo the rigor of research and academic study to ensure our understanding of how to protect and conserve acrylic paintings.

Acrylic Emulsion Paints were introduced during the later part of the 1950’s. These materials offered extraordinary promise as a revolutionary new artists’ medium because of their great clarity, ultraviolet light stability, incredible flexibility, quick drying and of course, water dispersibility. Acrylic still remains one of the most durable resin systems available for artists. Now that acrylic paintings have achieved a place within the canon of world collections, issues of conservation must be addressed.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970’s that any conservation articles actively examined acrylic paints. “The Cleaning of Colorfield Paintings,” a study published in 1974 by Margaret Watherston, looked at colorfield paintings, that were created by flooding areas of the cotton or linen canvas with extremely diluted mixtures of acrylic paint and water or solvent. In some places, very low levels of binder were present to hold the pigments in place, leaving the surfaces susceptible to abrasion. Large areas of these oversize paintings were left unprimed leaving vast expanses of raw canvas, prone to yellowing and embrittlement. This delicate construction made the paintings susceptible to changes in appearance with age, prone to attracting dirt and dust, and difficult to clean safely. It is reasonable to expect that these paintings, produced largely with water (or solvent), would be “underbound.” Diluting the binder with water makes a more fragile, discontinuous layer, even though the stain will still adhere to the substrate.

Information regarding acrylic conservation techniques was minimal and artists generally assumed acrylic to be simply indestructible. It wasn’t until 1990 that new concerns surfaced. Conservators were undoubtedly dealing with the issues of conserving acrylic paintings much earlier, but because it was so new, very few in the field were able to come forth and publish results.

Information regarding acrylic conservation techniques was minimal and artists generally assumed acrylic to be simply indestructible. It wasn’t until 1990 that new concerns surfaced. Conservators were undoubtedly dealing with the issues of conserving acrylic paintings much earlier, but because it was so new, very few in the field were able to come forth and publish results.

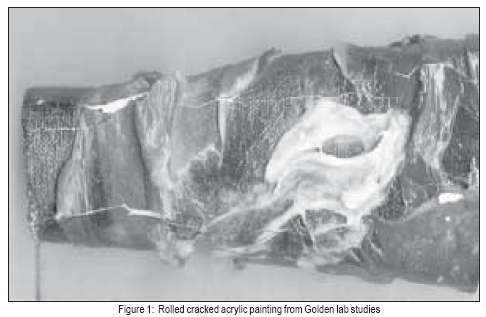

The problems surround two central issues: the sensitivity of acrylics to water and other organic solvents, and their thermoplastic nature. The sensitivity to water and solvents has raised questions surrounding cleaning, repairing and varnish removal from the acrylic. The thermoplastic qualities, (meaning the general softening of the acrylic in high temperatures and the hardening of the acrylic below 45 degrees F) have made storage and moving of acrylic paintings challenging. Even at room temperature, acrylic paintings can remain tacky, causing dirt and airborne pollutants to become bound to the dried acrylic film. In addition, acrylic film remains quite porous, enabling the retention of dirt and any solvents that may come into contact with the surface.

Conservators have recommended a few approaches to cleaning acrylic paintings, namely: mechanically cleaning the surface (which we discussed in Just Paint 5), encouraging preventative conservation, such as framing and putting the work behind glass, or accepting a degree of deterioration without action. These are very limited solutions given the considerable importance of acrylic paintings in recent art history.

In 1992, several articles appeared in the popular press which dismissed all modern materials, including acrylic artist paints. They were written for impact and sensationalism, with little attention to detail or substance. They simply perpetuated myths surrounding acrylic paints and all modern materials. In fact, some very positive information about the materials provided by scientists in the field was purposely left out of the articles.

A systematic and learned response to these assertions has been discussed, promised, and advocated through several conferences in which Golden Artist Colors has participated but few projects have been undertaken thus far. Conservators have found the limited existing works extremely helpful including studies by Marion Mecklenburg from the Smithsonian Center for Material Research and Education (SCMRE), studies of acrylic mediums by Dr. Paul Whitmore of the Center on the Materials of the Artist and Conservation Scientist, and Dr. Thomas Learner of the Tate Galleries in London. These studies looked at the effects of temperature and relative humidity on acrylics, changes in solubility of acrylics over cycles of both natural and accelerated aging exposure, and finally, the movement of additives through acrylic films.

For years, acrylics have been conserved using some of the same methods developed over the last 500 years for oil paints. Golden Artist Colors recognized an opportunity to contribute significantly to the advancement of understanding about acrylics. If acrylics were to be dealt with on their own terms, two things needed to happen. First a review had to be compiled that considered all the critical studies of acrylic paints. This included information from the conservation field and the paint and coatings field in general. We could then offer opportunities for additional studies which we hoped would lead to real options for the conservation community working on acrylic paintings. But more particularly, we felt confident we could develop some best practices for artists working in acrylic.

Developing the Tests

Our comprehensive review of the field included existing data on raw acrylic polymers, the polymerization process, additives and paint formulation, and properties of drying and dried acrylic films. It allowed us to come to some very interesting hypotheses to test. So, beginning in January 2000, we started pulling together the testing protocol for short term and long term testing with the intent of either developing with some possible approaches for acrylic conservation or at a minimum simply characterizing the changes that happen in the acrylic paint during aging, cleaning or conservation. We knew that we would at least be able to start to quantify the changes that occur when artists or conservators begin to clean acrylic paintings.

The hypothesis that followed from our review was: As we (and others) have shown that water soluble additives from the paint are exuding to the surface of the painting, we can improve the properties of the acrylic film if we remove these materials. Although seemingly a very easy idea to test, we are, after well over a year, still at the beginning of this research because of the many variables that need to be controlled.

The hypothesis that followed from our review was: As we (and others) have shown that water soluble additives from the paint are exuding to the surface of the painting, we can improve the properties of the acrylic film if we remove these materials. Although seemingly a very easy idea to test, we are, after well over a year, still at the beginning of this research because of the many variables that need to be controlled.

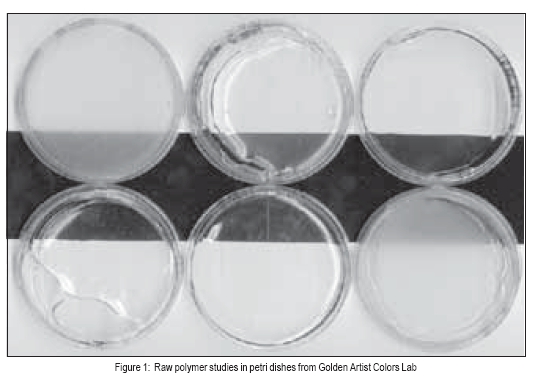

The first thing we needed to accomplish was to begin to understand the basis for the differences and commonalities in these materials. It is probably obvious to most artists that all acrylics are not alike. Acrylic artist paints are made up of a range of different raw acrylic binders. These different acrylics may contain different building blocks (monomers) used to create these large polymers. These building blocks may be used in different ratios, creating significantly harder or softer polymers, or possibly altering the lightfastness of the resulting polymer. The process for building these polymers will also alter the characteristics of the resulting acrylic. Some acrylics are smaller, some much larger, with related differences in characteristics such as gloss and adhesion. And finally just in the raw acrylic itself, there are many different constituents that are used to begin the polymerization process, as well as the addition of other additives. These materials are necessary to change the flow and leveling characteristics of the acrylic, its compatibility with different surfaces, and to add specific attributes, such as advanced adhesion onto leather or plastic substrates.

The type of monomer, the method, and the additives required for polymerization all affect the properties of the final polymer and, thus, the paint. Some are hazier than others, some are more yellow. They have different properties and viscosities and accept pigments and other additives in different ways. The paint formulator must accommodate for these differences.

Pigments, the second most important additive, are dispersed into the polymer and have their own sensitivity to water, as well as to other ingredients in the paint formula and other solvents. They also affect the dried paint film through their volume, concentration and their size and shape.

The volatile additives (those that evaporate) contribute essential qualities to the formulation and drying process and, for the most part, leave the paint during drying, though residual amounts may still be present in the dried film. These include the coalescing agents, ammonia and freeze-thaw agents. The nonvolatile additives, (those that don’t evaporate) equally necessary to achieve the desired properties of the paint, will remain in the dried film-surfactant, thickeners, defoamers and preservatives. Their presence in the dried film may affect conservation and will need to be addressed in future research.

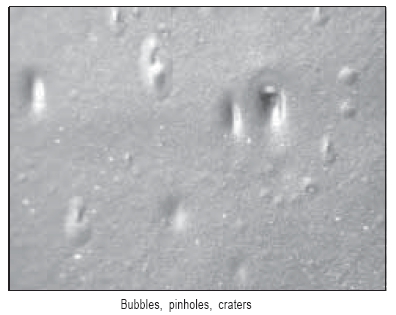

Finally, the dried film is extremely varied depending upon the application method, the substrate on which the work was painted, as well as all the other variables mentioned above. Bubbles, pinholes, craters, pigments sitting up on the surface, underbound paints all serve to create an incredibly diverse paint film. At the least, even the most perfectly applied film will contain pores or microvoids. In fact, the porosity of acrylics is acknowledged as positive in some applications for allowing water vapor to pass through the paint film, reducing the risk of delamination. The porosity of the acrylic also provides for the exceptional mechanical adhesion of acrylic paint layers to one another. Of course, a porous paint film in artwork has many implications for painters and conservators. A porous coating may trap air pollution, dirt and foreign matter, encouraging biological growth. This porous film may trap conservation cleaning agents via capillary action, leaving highly concentrated pockets of solvent that can interact with the painting film on a long-term basis, potentially causing weakening of the film

Considering these variables, we mapped out an approach to begin short term studies to characterize the paint surfaces resulting from altering the conditions of drying, the cleaning process and the substrates utilized. We also embarked on the longer term study to look at the changes which may occur when we remove additives from the surface and how this might effect the aging, mechanical properties, dirt pickup, and visual characterization including color and gloss changes in the paint film.

Current Research

Our current research focused on investigating the role of surfactants. Surfactants are added to the raw polymer to initiate polymerization and they are added to the paint formula to help disperse pigments into the polymer, ease coalescence and help the paint wet-out the substrate upon application. A series of studies in the coatings industry and two of our own studies suggest that surfactants are present at the surface of the dried paint film, rather than (or in addition to) being locked away within the film. The housepaint industry acknowledges that surfactants will be washed away by the rain when the paint is young and that this is desirable because it will reduce dirt pickup and staining and will even-out the surface gloss.

We have chosen to look at the observable effects of washing on the acrylic film under natural and accelerated aging conditions. In our attempt to look at practical solutions we looked at cleaning acrylic painted surfaces with a 100 percent woven cotton cloth.

We used weights to duplicate the pressure that might be used by an adult hand washing off a dusty surface. We used both warm and cold water as well as solvents including ethyl alcohol and mineral spirits. The ethyl alcohol created significant changes in the acrylic film in each test. It clearly smoothed out the acrylic and created traction lines throughout the film. The most surprising results however, were that 20 passes with cold or hot water over the surface, as well as the mineral spirit solvent showed no observable change under magnification. We did detect changes in gloss in the films, with most tests showing an increase in gloss. This would have been expected based on one of two possibilities; we are burnishing the surfaces, or we are removing some of the water miscible additives that find their way to the surface of the acrylic. We did detect under magnification some very random scratches, spaced very far apart. These scratches were on the order of 3-10 microns in width. They occurred no more frequently then the scratches under tests where we dry rubbed the acrylic surfaces with the cotton cloth. The other significant finding was that certain colors under the water washing left a visible residue of pigment on the wet cloth, specifically the raw umber samples.

Our next step, using the same paint films, was to create conditions that caused an observable change with water. In one series we maintained the same amount of pressure, with 80 passes of the cotton cloth. In another series of tests we doubled the amount of pressure with 40 additional passes. Under these conditions we were able to see changes in the sample with the additional weight. These changes included burnishing of the surface and surface scratches. We were also able to detect water spotting in some of the samples.

We have repeated the washing of these surfaces to continue to look at changes over time and with repeated washing. Of special note is that by the third washing, no residue of pigment was noticeable on the cotton cloth when washing the raw umber. We also saw that the warm water created a significant increase in gloss in the raw umber sample compared to the cold water. Finally, the mineral spirits created a significant burnishing of the surface in both the test with additional passes and those with additional weight.

Our next series of tests looked at the effects of water on the acrylic film. Even a short exposure of just a few seconds will visibly alter the surface of the acrylic. We wanted to examine if these changes were reversible. By placing drops of water on the surface we examined the amount of time required to produce the maximal change in color and swelling of the surface. We determined that 15 minutes was sufficient given the colors we were working with. This created a profound localized swelling and increase in tint of the paint film. Once the water droplet was blotted from the surface, both observable swelling and color change were reversed within minutes.

Our ongoing series of studies that we hope to report on in the future include dust build up of paint films, blocking (stickiness) before and after aging and washing, gloss and color changes, changes in flexibility and any changes in the film’s ability to be affected by water.

Current Observations:

Although our work is still at the preliminary stages we are quite excited to see the reversibility of the effects of water on the surface of the acrylic films. The most startling result was that there seem to be some conditions of washing the acrylic film that may reduce the possibility of damaging the surface of the painting. We continue to look at the differences in hot and cold water washing. Several studies suggest that warm water is more effective at removing additives from the surface, but work done by Marion Mecklenburg looking at the effects of temperature on the acrylic film suggest that the acrylic becomes much harder in colder temperatures so colder water may reduce potential burnishing of the film. In our tests with raw umber this does seem to be the case. Of special importance to us was seeing that the mineral spirits could be used under certain conditions on the surface without showing changes to the films. This coincides with our assessments of paintings in which the MSA varnish was removed and certainly provides some additional confidence to these empirical results.

Tests need to be conducted on the complete range of acrylic colors to determine which may be more sensitive to washing than others, and what those particular effects are. Photomicrographs showed the wide range of textures within each acrylic color. Tests will continue to look at cleaning dusty surfaces. It is our strong belief that dusty surfaces need to be cleaned by dry methods as outlined in our Just Paint #5 article “Techniques for Cleaning Acrylic Paintings” before attempting to wash even the most stable surface. It is likely that dust particles will act as sand paper if they are not sufficiently removed from the surface.

It still remains to be studied if this washing will have an even more positive effect on the painting surface. So before taking your painting in the shower with you, a good deal of additional work needs to be completed before we can make wide sweeping recommendations on cleaning these surfaces, but we are slowly opening up some very promising options to be able to continue to study. Artists are looking for practical solutions for conservation that offer the best results. We have started our own research in an attempt to look for practical solutions for artists. And when we can’t create solutions, at least we will have documented what may happen should you clean or otherwise conserve your own paintings. If we could prove that removing these additives improved the properties of the film, then we could begin to create potential best practices for artists to consider when cleaning. Even if we couldn’t show improvement, but only characterized the effects of cleaning, we would still have a tool so that an artist could make their own judgment as to how to proceed on their paintings.

Artists will often call their local museums or art conservator to try to get advice on the best practices for taking care of their work. This advice is generally informed and on target. But we would suggest that sometimes conservators respond to an artist’s request with treatments that are well beyond the scope of most artist’s abilities and resources. Obviously, this gets more complicated when the painting is purchased, becomes part of a permanent collection, or is otherwise no longer owned by the artist. We hope that our research will prove useful for artists and the conservation community in an ongoing effort to understand the effects of time on our relatively new medium.

About Golden Artist Colors, Inc.

View all posts by Golden Artist Colors, Inc. -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post