EDITOR’S NOTE (4/26/23): Please note that Polymer Varnish has been discontinued and replaced with Gloss Waterborne Varnish. You can read more about it here.

As with any surface around the home, office, or especially, in a public place, paintings become a depository for airborne dust. They can also get touched occasionally, either inadvertently or purposefully, and may become soiled from the contact. Acrylic paintings have unique attributes that affect their propensity for attracting and retaining dirt and grime. One theory is that they are prone to carrying a static charge, which results in greater dust attraction and retention. Regardless of whether this characteristic substantially affects dust attraction, based on our observations of acrylic paint and conversations with conservators, we know that the thermoplastic nature of the paint film can result in significant adhesion of particles to the surface.

“Thermoplastic” means that the relative hardness and flexibility of the polymer are influenced by changes in temperature. As temperatures increase, acrylic becomes softer, more flexible and may become tacky. As this happens, any debris present can become adhered to the surface and will subsequently require relatively aggressive methods for removal. While the manufacturer of acrylic paint can choose harder polymers that are less prone to this problem, there are trade-offs associated with their use. The principal virtues of acrylic paints are their inherent film flexibility and lack of brittleness. Using harder acrylic polymers would result in a painting being more susceptible to cracking from impact or movement during shipping as the result of raising the glass transition temperature (GTT), the point at which the film will snap like glass instead of bending as plastic is expected to. A higher GTT increases the risk of permanent damage to a painting from mishandling. GOLDEN Acrylics are formulated to optimize flexibility of the paint film and to maintain a reasonably low GTT. However, this does mean that unprotected paintings are at greater risk of requiring more aggressive cleaning practices.

Characteristics of a painting’s construction also affect its tendency to retain foreign material and its subsequent ease of cleaning. These should be considered when choosing materials to execute a work and when deciding on display locations and conditions. For example, use of acrylic paint allows the artist to build incredible impasto surfaces that dry quickly, without deforming. The resulting terrain of this type of surface contains numerous horizontal planes which act as shelves for dust to land on and become embedded into over time. The surface may also contain concave areas and hollows in which debris can collect. Compounding this characteristic is that these areas can be extremely difficult to clean.

Characteristics of a painting’s construction also affect its tendency to retain foreign material and its subsequent ease of cleaning. These should be considered when choosing materials to execute a work and when deciding on display locations and conditions. For example, use of acrylic paint allows the artist to build incredible impasto surfaces that dry quickly, without deforming. The resulting terrain of this type of surface contains numerous horizontal planes which act as shelves for dust to land on and become embedded into over time. The surface may also contain concave areas and hollows in which debris can collect. Compounding this characteristic is that these areas can be extremely difficult to clean.

On a more microscopic level, the acrylic paint film is relatively porous, caused by tiny voids left as the water evaporates during the drying process and protrusion of solids near the surface of the film as it shrinks during drying. The subtle texture that results provides a surface that is both easier to soil and more difficult to clean, similar to the difference that might be noticed in gloss vs. satin interior house paints. This characteristic is accentuated with certain specialty products. For example, GOLDEN Pastel Ground is designed to abrade and retain soft materials that contact it, while GOLDEN Absorbent Ground is especially effective at drawing stains into the surface. Therefore, left unprotected, both are at higher risk of becoming soiled and would be more difficult to clean than regular GOLDEN Acrylic Gesso.

Another characteristic of acrylic paint that provides both a benefit and reason for caution is its ability to function as an adhesive, particularly during the final stages of drying. This property is effectively used by collage artists wanting an archival means of assembling a work because the acrylic does not become brittle with age, remain water resoluble or discolor like many traditional glues. However, this property may result in paintings becoming permanently marred if foreign material is allowed to touch the surface during the final stages of drying, as might happen if dust from sanding is in the air of a studio.

The ability of the binder to function as a stand alone medium for painting, as with GOLDEN Gels and Mediums, adds another dimension to the visual effect possible with acrylic. If the intent is to look through a layer of relatively clear media, a dirty surface is quite distracting. Too often, a clear acrylic dispersion media (i.e., GOLDEN Polymer Medium) is selected as a final topcoat in lieu of a removable varnish. Used as such, there is the risk that once dirty, there is no assurance that it can be effectively cleaned, especially without affecting light transmittance of the film due to potential physical abrasion from the cleaning process.

Overuse of additives to achieve performance variations in acrylic paints, such as GOLDEN Retarder to slow drying or Flow Release to enhance staining, can also affect dirt retention properties of the paint film. Retarder does increase the open time, but will also lengthen that period when the paint is no longer workable, yet is still not fully dry. During this time, the paint film is far more susceptible to retaining airborne contaminants that contact it. Similarly, Acrylic Flow Release used in excess can result in a paint film that remains extremely tacky for a long period of time.

Knowing why acrylic paintings may eventually require cleaning is helpful because this knowledge can be used to make choices that will aid in avoiding or postponing the cleaning process, which is the first level in the hierarchy of conservation practice, i.e., prevent the need for intervention.

Why Minimize the Need for Cleaning

Every time a painting is touched, it is at risk of being changed or damaged on some level. In taking the long view that art materials should be manufactured to be as archival or long lasting as possible, the advice offered herein for cleaning practices follows a similar theme. The fewer times a painting is cleaned, the less chance there is for permanent damage to occur. Sometimes these effects are almost microscopic, such as minute scratches that may occur if dust or an abrasive cloth is wiped across the surface or the concern that use of mild cleaning agents will remove small amounts of soluble components of the paint. At the other extreme is the possibility of permanent visual changes that could result from the wrong choice of cleaning method by an untrained individual, such as a “tide line” appearing on a stain-painted canvas because a wet cleaning method was used, or burnishing of a matte surface resulting from trying to wipe away dirt. Worse yet, for example, would be if a fragile paint film is aggressively cleaned and large, visible portions of paint are accidentally removed from the support.

Regardless of the amount of change, in the context of thinking that art should be capable of lasting forever, any change or potential for change to the piece through cleaning conflicts with this end. For this reason, cleaning of paintings by professionals in fine art conservation is the best approach to maximize longevity. They employ a tiered approach to cleaning that starts with the least intervention possible and progressively becomes more aggressive as needed. However, there are upper bounds of intervention dictated by the risk of the cleaning activity permanently affecting the painting, balanced against the anticipated incremental gain provided.

A General Approach to Cleaning Acrylic Paintings

In our conversations with people in the field of art conservation, we often ask “How do you clean acrylic paintings?” Although the most common answer is “with great difficulty,” we’re looking for something more concrete. From these conversations and the general lack of material on the subject in conservation publications and symposia, it is our impression that there remains room for further research in this area. However, there are commonalities in the approach to cleaning paintings that are worth describing. The following series of steps is a compilation of approaches of several conservators with whom we talked. Because of the lack of definitive research in this area, some of the ideas presented here should be considered experimental and may be debatable.

- At the first evaluation and at each subsequent step, the question must be asked, “Is the anticipated intervention necessary?” Current ethics in conservation prescribe a minimalist approach to the treatment of paintings. This is due to the recognition of irreversible changes that have occurred to works of art during the infancy and adolescence of the conservation profession. A simple treatment involving minimal risk and contact with the painting may be easily warranted, while an aggressive wet-cleaning method without assured outcome is cause for consideration.

- A careful evaluation of the surface is performed to determine if the piece can withstand whatever plan of treatment is designed. Is the surface stable? Are there areas of poor adhesion, weakly bound paints or fragile areas? What is the surface sheen and how will it be affected? Is the piece varnished, and if so, can the varnish be safely removed? It is extremely useful to know the materials used by the artist in the painting. For this reason it is helpful for the artist to provide documentation with the painting that details support preparation, type of media, isolation coat and varnish used. A copy of this record should also be retained by the artist.

- The nature of what is being removed is determined. Is it dirt or grime on the surface? Is it dirt embedded, or both?

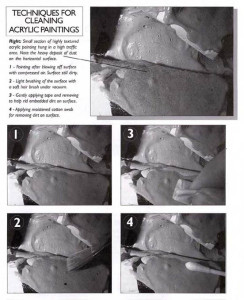

- Realize that any surface contact should be minimized, so initial cleaning attempts should be designed accordingly. One method is to use compressed air to blow away surface dust. Another technique involves using a soft sable brush to lightly brush the surface in order to dislodge dust while holding a vacuum source, off the surface, to capture and remove debris.

- If the dirt is embedded and vacuuming doesn’t remove all of it, the next level of intervention involves dry cleaning methods (not to be confused with solvent washing of clothing) with more aggressive surface contact. Materials described as hydrophobic sponges and molecular traps that are able to overcome the physical adhesion between the dirt and paint film, without imparting their own residue, are used. Erasers and similar materials that may fill in the pores of the paint should not be used. It may be possible to use tape to lift dirt from a painting, as long as there is assurance it will not leave a residue. Whenever a cleaning method is used involving surface contact, it is advised that paintings on flexible supports be suitably backed to minimize surface deflection and equalize working resistance.

- As a last resort, a cleaning method utilizing moisture may be required. Generally, this applies only to stable, undamaged surfaces. Potential dangers of such an approach are that liquid cleaning may actually drive dirt deeper and make matters worse or can create tide lines in the support, which result from solublized material concentrating at the wet edge. It is also theorized that wet cleaning at the surface will create rheological differences in the paint film.

An effective and time tested cleaning technique is euphemistically referred to as “enzymatic cleaning”. It involves moistening a clean cotton swab in the mouth and rolling it across the painting’s surface. Saliva is warm and contains enzymes which act upon both lipids and proteins, two common components of “dirt”. It is important to note that the correct procedure is to roll the swab across the surface, as opposed to rubbing it, which could cause abrasion. The process must be extremely gentle and it is important to keep the moisture on the surface to a minimum. The procedure is started by testing in a small area of the painting judged to be least noticeable. At each step of the treatment, the painting is carefully examined for changes in gloss and color pickup on the swab. Sometimes it is necessary to work through “Japanese Tissue”, which allows the dirt and moisture to wick away from the painting. Deionized water may also be an appropriate choice for moist cleaning.

As an aside to the procedure of working with a cotton swab in small areas, we have heard concerns that this may lead to the surface appearing mottled. Presumably, this would result from slight differences in factors such as the amount of moisture or pressure used, or the amount of dirt removed. - The final step (and the first step) is to evaluate the conditions which led to the need for treatment. Can a cleaner environment be found? Should a removable varnish be applied?

Recommendations

- If aesthetically appropriate, apply an isolation coat and varnish to acrylic paintings to facilitate ease of cleaning. Use a removable varnish such as GOLDEN Polymer Varnish or MSA Varnish. The removable varnish layer allows the painting’s surface to be cleaned at a much lower risk. If it becomes scratched or if dirt does become permanently embedded in this layer, the varnish layer can be sacrificed by removing it (consult GOLDEN Technical Data Sheets for Polymer Varnish and MSA Varnish for removal techniques), and a fresh layer of varnish can be applied to restore the painting to its original appearance.

- Practice proactive prevention. Display paintings in the cleanest, lowest traffic areas possible. Vacuum or mop these areas, rather than sweeping, to minimize airborne dusts.

- Minimize exposure of acrylics to elevated temperature, especially in combination with dusty conditions. Such areas may be near hot air inlets, in direct sunlight or attics.

- Minimize frequency of direct contact, such as dusting of unprotected acrylic surfaces. Instead, use compressed air.

- Seek out professional services as appropriate for the piece and conditions. By virtue of training, experience, tools and techniques, the risk of damage to the painting will be much less if it is cleaned by a reputable professional in the field of fine art conservation.

- Recognizing the need for specific techniques for protecting as well as cleaning acrylic paintings, we invite response from conservation professionals who wish to share their experiences.

The following people are thanked and acknowledged for independently sharing information for this article.

Leni Potoff,

Duane Chartier,

ConservArt Associates

Susan Blakney,

WestLake Conservators, Ltd.

Any errors or omissions are the sole responsibility of the author.

Ben Gavett,

GOLDEN Artist Colors, Inc.

About Golden Artist Colors, Inc.

View all posts by Golden Artist Colors, Inc. -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post