We all get tripped up and surprised sometimes. Even the simplest description can set in motion assumptions that lead us to expect one thing only to be sitting there, moments later, head slightly tilted, a quizzical glance showing equal parts frustration and fascination. Which is where we found ourselves a few years back when testing a variety of inks and how they perform on our various grounds, pastes, and mediums. Among the ones being tested was the tried and true India Ink – richly black, shellac-based, and solidly waterproof. At least as far as the label said. And one would certainly think describing something as waterproof is straightforward and plain enough to avoid confusion. If you look at the many examples we show in the Just Paint article, Make a Mark, you can clearly see that the ink holds its own through a range of finger rubs and water washes, only becoming smeared when using rubbing alcohol. Which, after all, is the common solvent for shellac, so not all that surprising.

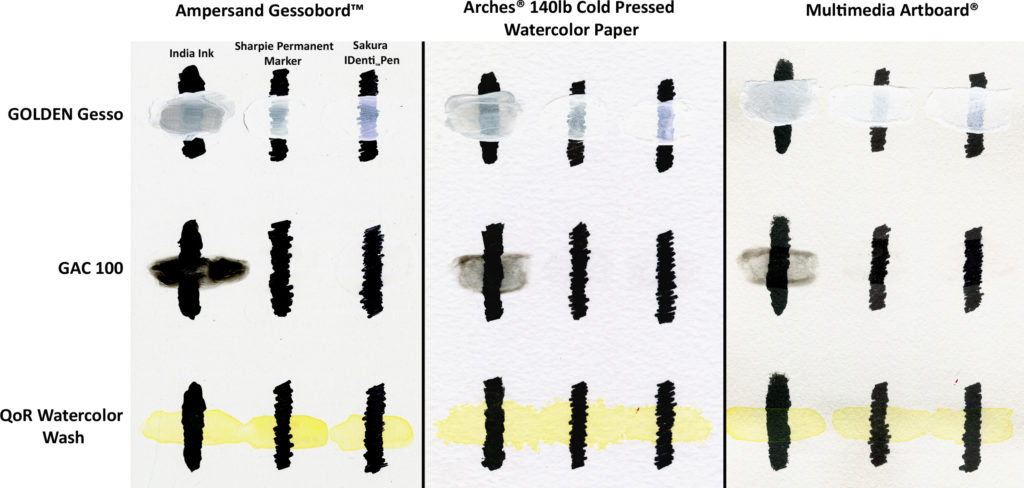

The curiosity comes when you attempt to brush over the India Ink with any of our mediums, gels, grounds, or paints. All of a sudden what was waterbased seems quite water soluble, the sharp edges of the wash or line becoming easily liquified with barely any effort. This is something you can easily see in Image 1 where we tested India Ink, Sharpie® Permanent Marker, and Sakura’s IDenti™ Pen by brushing over them with our GOLDEN Gesso, GAC 100, and a wash of QoR Watercolor. The surfaces we tried included Ampersand’s Gessobord™, Multimedia’s Artboard®, and Arches® 140lb cold pressed watercolor paper.

Click for larger image.

So, what is happening? As it turns out, while the India Ink is indeed ‘waterproof’ – in the sense that water alone will not cause it to run – it remains sensitive to the ammonia and other alkaline materials that can typically be found in acrylics, not to mention many household cleaners. Any surprise is simply caused by the fact that we think of acrylics so strongly as water based that other factors, like ammonia sensitivity, might go unnoticed. And in a case like this, if one imagines a drawing in India Ink being over painted with acrylics, the consequences could spell irreparable ruin. In terms of what one can do, there are a couple of options. Obviously using a different ink, as the tests above show, might be one solution, although each ink would need to be tested beforehand and the character of the drawing would likely need to change. Another route would be to first fix the India Ink with a couple coats of Archival Varnish, thereby locking it in and providing a barrier that protects it. As you can see in Image 2, after applying two coats of Archival Varnish Satin to India Ink swatches on all three substrates, they were able to be overpainted with GOLDEN Gesso and GAC 100 with no sign of being disturbed:

Further Explorations

While the above might provide a nice and clear case of discovering an unexpected ammonia sensitivity in an application, and a cautionary tale of needing to always test one’s process, there remains additional curiosities to share.

Some of the common primers for sealing wood in commercial applications, as well as substrate preparation for artist panels, are white pigmented shellac products such as Zinnser’s B-I-N®. These types of primers have a well deserved reputation and following because they are fast drying, an excellent blocker of tannins in wood, and able to seal off dye-based inks that can bleed into water-based latex paints. So the immediate question was whether B-I-N, as one widely available example, had a similar sensitivity as shellac-based inks? And would GOLDEN products cause the same issues that we saw earlier? The results of our testing showed some additional twists worth exploring.

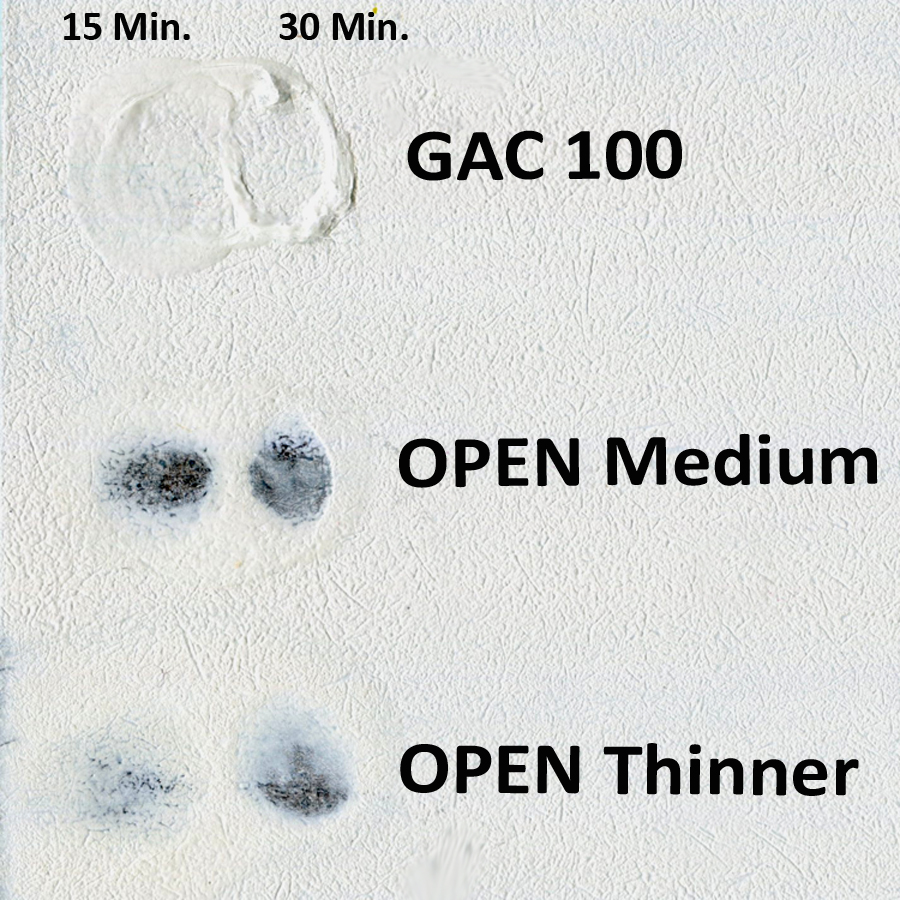

The main surprise is that B-I-N appears to hold up to regular GOLDEN products quite well, at least when applied at common brushed-on thicknesses, but fail quite readily when coated with OPEN Medium or Thinner. You can see this in Image 3, where we applied a small amount of GAC 100, OPEN Medium, and OPEN Thinner on top of two coats of B-I-N on a hardboard panel. After 15 minutes we rubbed an area using a cotton swab to see if the coating would dissolve or loosen, and then repeated the process after 30 minutes. Clearly the coating stayed intact under GAC 100 but readily came off under OPEN Medium and, while slightly less dramatically, also under OPEN Thinner.

As to why GAC 100 left B-I-N intact while easily dissolving the earlier India Ink, the most likely explanation is the strength of shellac in B-I-N versus the very slight amount found in India Ink which, like all inks, relies mostly on the pigments nestling down into the fibers of an absorbent surface rather than being locked down tightly by a binder. It is also important for inks to not cause nibs to become easily clogged, so keeping the binder levels to a minimum makes sense from that standpoint as well. In terms of OPEN, however, the ability to dissolve B-I-N seems clearly linked to its unique formulation which results in the amines being able to interact with the shellac binder in a much more aggressive fashion.

There is clearly more to explore here and the main takeaway is really about testing your materials and processes for these types of unexpected results. Waterproof, lightfast, non-yellowing, acid free, archival, permanent are all words that conjure up simple clear notions until we start to poke and prod them, asking how much, for how long, and under what conditions. Among many other things. And as we have seen, all too often, the answers you get might just surprise you.