Oil paints dry through oxidization, so access to air seems clearly important, but what about light? How much does exposure to different light levels impact the drying process? Surprisingly, for a question that seems so basic and fundamental, there is not a lot of information or test data that one can find. While a few scattered studies do turn up in the literature, they are focused almost solely on the oil alone and are not based on a range of typical light levels and a variety of common colors. What follows describes some of the preliminary testing we have done in this area, and although there were no clear and definitive conclusions, we did end up with some tantalizing curiosities and patterns that can help inform best practices and provide areas for further investigation.

Test Layout

The testing included 10 Williamsburg Oil Colors chosen from three different drying categories and including both reactive and inert pigments:

- Fast: Raw Umber, Phthalo Green

- Medium: Cadmium Red Medium, Cobalt Blue, Ultramarine Blue, Titanium White, Titanium-Zinc White, Flake White

- Slow: Quinacridone Magenta, Lamp Black

These were applied as 6 mil drawn downs, about the thickness of two sheets of common copy paper, onto uncoated polyester film.

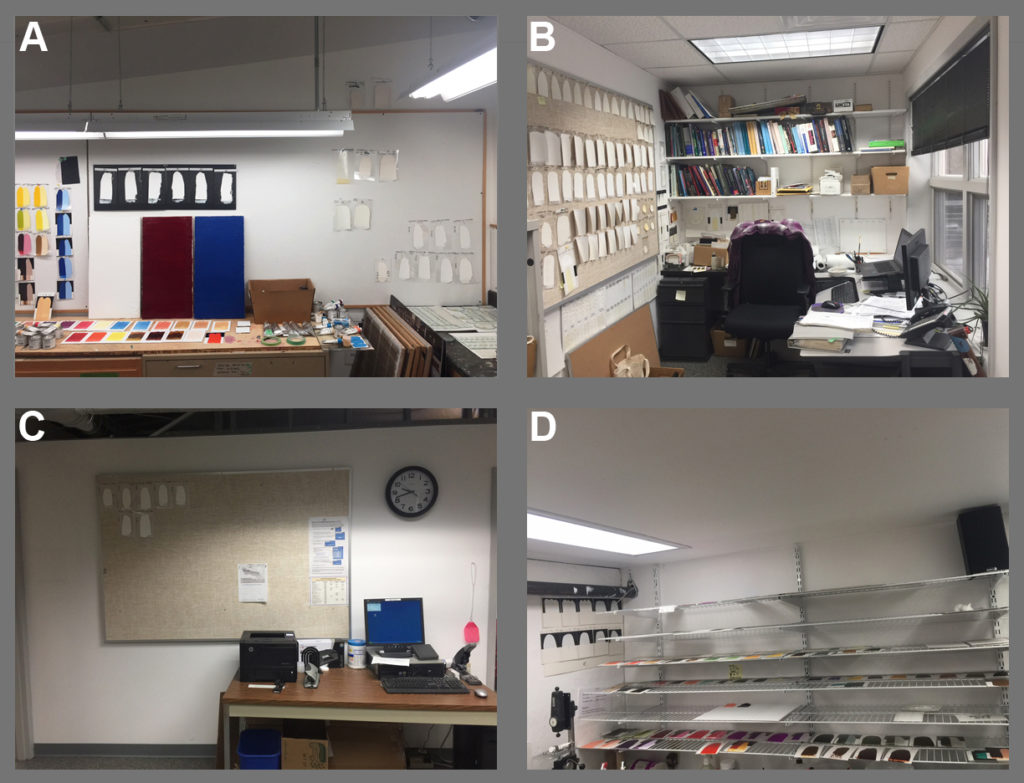

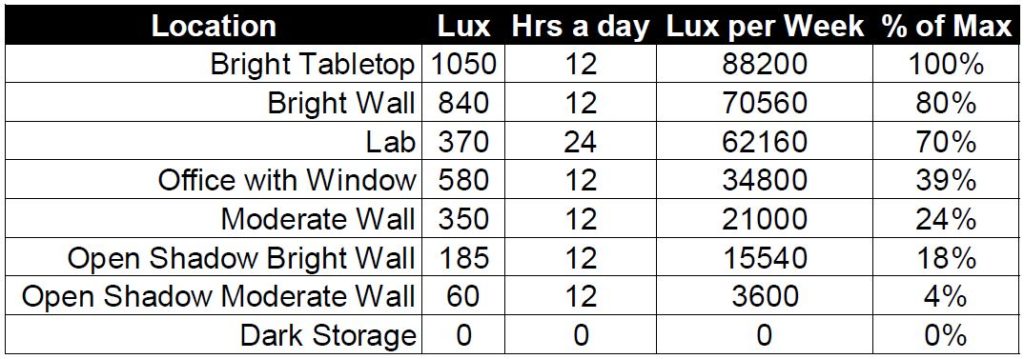

Samples were then placed in one of 8 different lighting situations. All lighting involved standard fluorescents, although the different types (daylight, cool, full=spectrum, etc.) were not controlled for. Lux levels, or the luminosity and brightness of the light, were measured using an Extech LED Light Meter.

Lighting situations and the corresponding lux levels:

- Brightly lit table directly under light fixture (1050 lux)

- Brightly lit wall adjacent to table (840 lux)

- Office wall facing window (580 lux)

- Drying shelf in Lab (370 lux)

- Moderately lit wall (350 lux)

- Open shadow on brightly lit wall (185 lux)

- Open shadow on moderately lit wall (60 lux)

- Completely dark room (0 lux)

Weekly totals were then estimated based on the number of hours those particular lights would be on during a normal week.

Temperature and humidity were not controlled for, so any differences at the various locations were not taken into account.

A separate parallel study involved 6 mil drawdowns of Titanium-Zinc, with one sample placed in the dark room and additional samples transferred there after being exposed to either direct daylight or hung on the brightly lit wall for various intervals. This was to see if initiating the drying of a sample in the light impacted the length of time it took to finish drying in the dark.

Test Results

The test results, as you will see, contained more than a few surprises. Some colors were unaffected by the amount of light, drying at the same rate regardless of location, others showed a very moderate increase, while for a few the differences were dramatic.

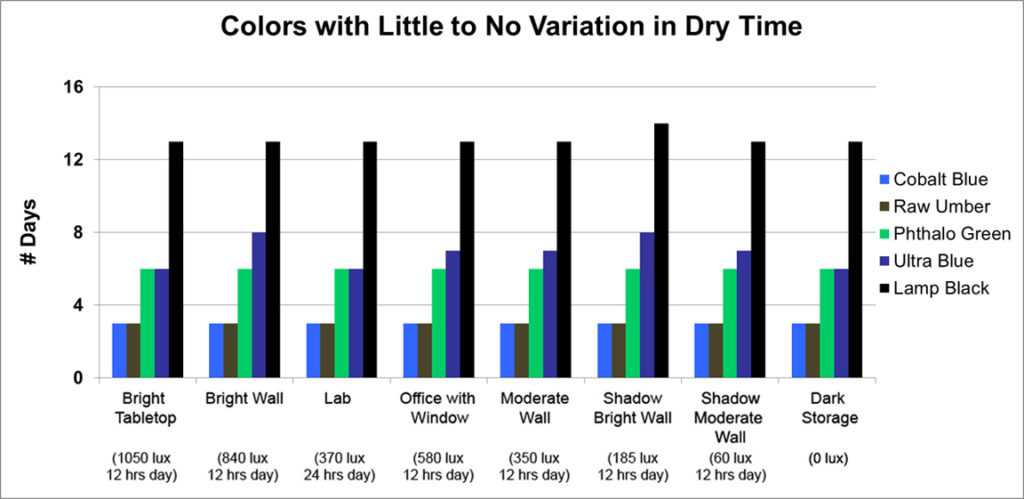

First up are the five colors that were, for the most part, invariable: Cobalt Blue, Raw Umber, Phthalo Green, Ultramarine Blue, and Lamp Black:

This is an unusual group by any measure. While the pigments in three of the colors (Cobalt Blue, Raw Umber, Phthalo Green) contain elements that can act as driers, such as cobalt, manganese and copper, making it is easy to think there might be an internal mechanism that allows them to kickstart the drying process on their own, this is not true of Ultramarine Blue or Lamp Black. Indeed Lamp Black is a notoriously slow drier and chemically inert, so one would assume it would be greatly impacted by light exposure, but it was amazingly consistent regardless of the amount of light.

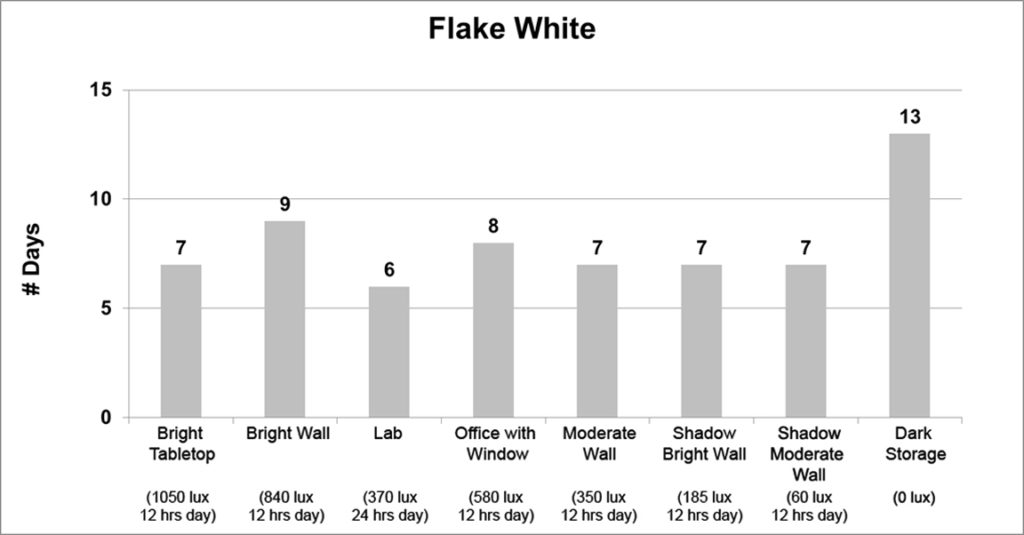

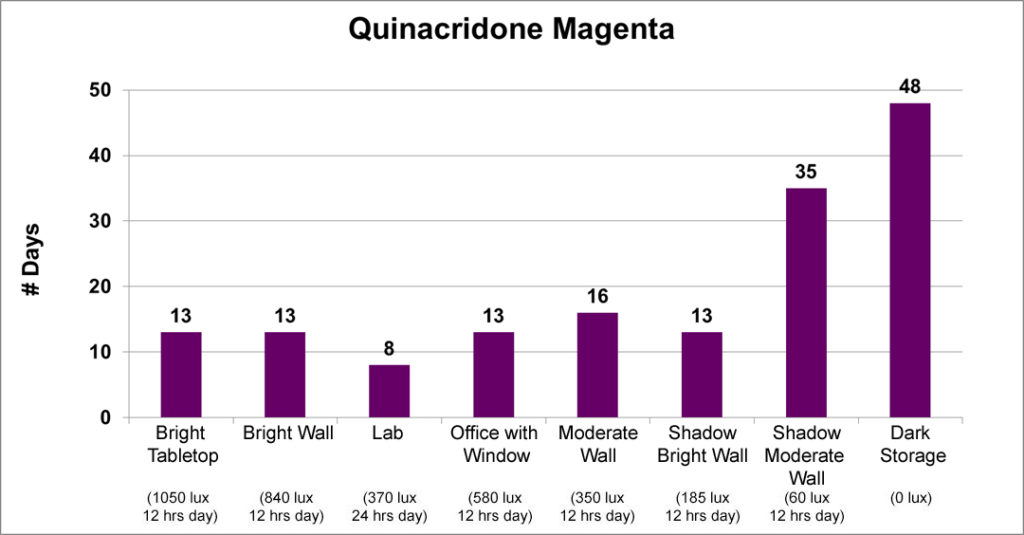

The second group is made up of just two colors, Flake White and Quinacridone Magenta. Under most circumstances, both these colors had fairly consistent dry-times, but showed a clear increase when placed in the dark or even in very subdued light, as in the case of Quinacridone Magenta. The variations in some of the data is most likely due to differences in sample preparation and where a particular sample was placed; although the sudden drop in drytime for the Quinacridone Magenta located in the Lab remains an unexplained anomaly.

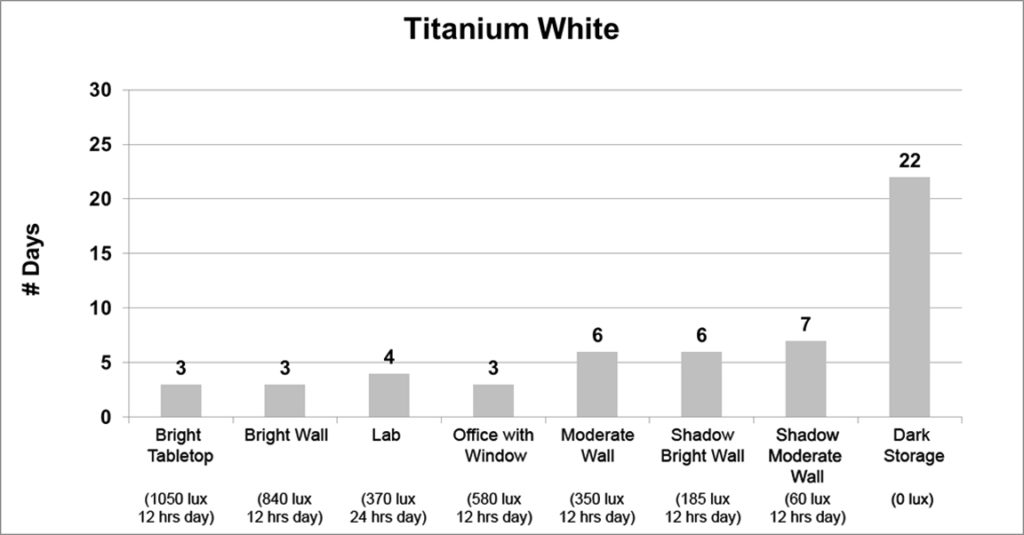

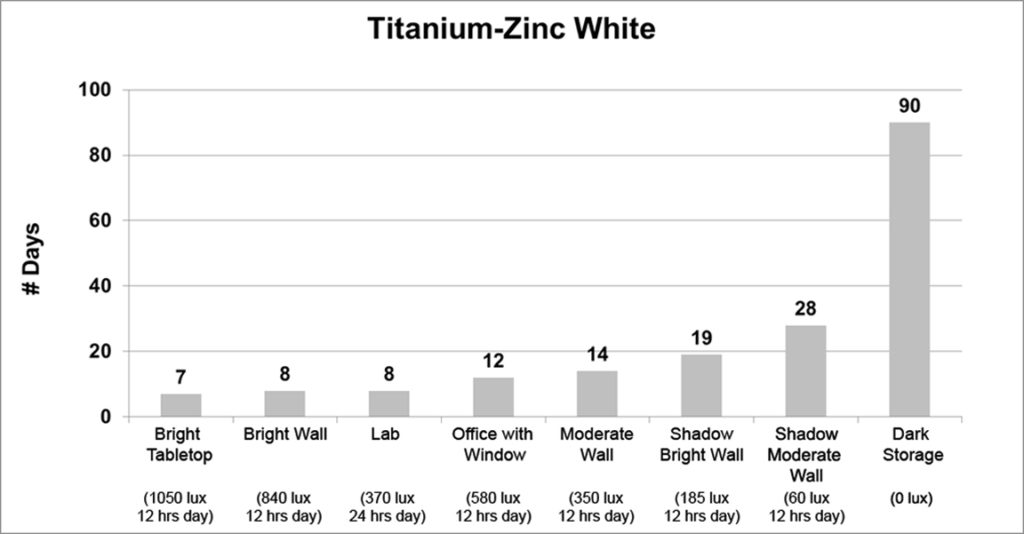

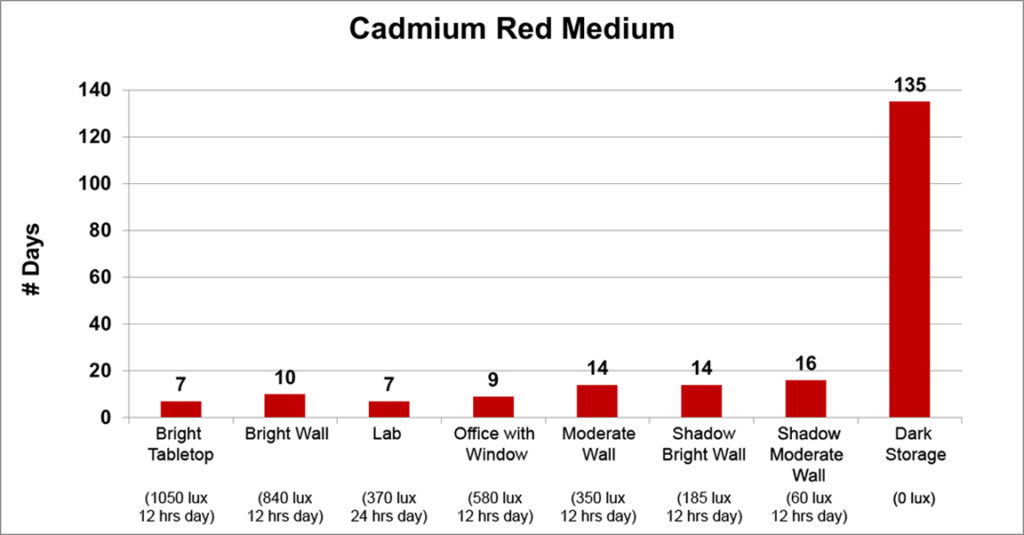

Finally, the last three colors (Titanium White, Titanium-Zinc White, and Cadmium Red Medium) exhibited a strong correlation between light levels and dry times. As the light levels grew lower, the drying times steadily increased in a gradual and logical manner, ending with a very sharp spike in dry time when placed in the dark:

While both Titanium White and Titanium-Zinc dried 3 times slower in dark storage than the open shadow of a moderately lit wall, jumping from 7 to 22 and 28 to 90 days respectively, Cadmium Red Medium displayed an extraordinary increase in dry time, going from 16 to 135 days, or about 4 1/2 months.

Implications and Next Steps

We undertook this testing with the common assumption that light levels would impact dry times in some regular, predictable way that would be easy to draw conclusions from. However, the results have ranged over a wide area, and given the small sample size, there is no clear, singular factor that explains why some colors are in one grouping or another. Also, what was most surprising was not the dramatic jumps in dry time when colors were placed in the dark, but those cases where light levels or even the absence of light appeared to make no difference whatsoever. While pigments appear to play the central role in these differences, much more testing will be needed to understand how. And naturally, we are left with other questions as well: How do mixtures of different colors behave? Does layering one color over another make a difference? Are all the results similar under different lights – fluorescent, halogen, incandescent and LED? Is the presence or absence of UV important? These are some of the areas we hope to explore in the future, in addition to expanding the number of colors and types of pigments being tested.

Best Practices

While it is hard to construct best practices based on limited testing, it still seems reasonable to assume a few things that can help your studio practice:

- Paintings placed in the dark or in subdued lighting might dry significantly slower. This includes when paintings are placed in drying racks or turned against the wall.

- Conversely, paintings exposed to ample amounts of light should dry more quickly, although which types of light are the most effective still needs to be tested.

However, because pigments appear to have a large impact on the results, the above points are at best broad, general guidelines. Individual paintings are invariably complex, with multiple pigments being blended together and mixed with various mediums. Exactly how all of that impacts the drying times is an area that is just now being explored for the first time.

About Sarah Sands

View all posts by Sarah Sands -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

Until you you can separate the effect of heat (temperature) on oxidation of oil paints, you will not really know the effect of light on oxidation. Your test results indicate the combined effect of heat and light.

Do you have any test results on the effect of temperature on oil paint drying (oxidation)?

Hi Charles –

Thanks for the comment. I agree temperature is a variable that needs to be accounted for to get a complete picture, and since heat accelerates all chemical processes, there is every reason to believe that it will speed the drying times across the board. But still important to understand to what degree and the amount of impact versus light exposure. As you can imagine, it is a little tricky to control for temperature in a test, while keeping other variables constant, but we are working on some test designs that will allow us to try to do some of this in future rounds. For now, as I stated in the article, the most surprising thing is not that light had an impact, but that a full half of the colors exhibited no or little change in drying time even in complete darkness, with temp at typical ambient conditions as might be found in most studios and homes. That more than anything is what needs to be explained and understood.

But more to come…..it will take a few rounds to really suss this out.

Dear Ms. Sands,

I applaud this line of inquiry. However, one issue in the experiment design stuck out to me: the method or interpretation of what constitutes a dry film, when it is present. You didn’t mention how the swatches were sampled or tested for evidence of dryness. Say, as opposed to “skinning”. Were the samples touched with some standardized probe or just the finger of a technician?

I am looking forward to hearing about future discoveries your and your team at Golden/Williamsburg might make.

Best wishes,

Mike Rothman

Illustrator

http://www.rothmanillustration.us and

http://www.michaelrothman.com

Hi Michael –

Thanks for the comment and great question as that is important and likely should have been noted. My oversight on that. Our dry time tests are pretty aggressive in that we take a toothpick and draw it across the surface with constant, reasonable pressure and consider it dry when it can go across the entire width without going through the paint or causing it to rip. This gets around the fact that paints will dry along the edge before the center, and gets one past the more ambiguous ‘touch dry’

I’m surprised there was no inclusion of sunlight in the testing format. I know of several oil painters who have constructed UV light boxes with special UV-emitting lights to speed the drying of their oil paints.

Hi Bev –

We did include some trials with sunlight, and got some interesting results, but wanted to expand that section more before writing anything up. So look for that to be discussed in a future article. For now we just wanted to share these initial results, which were meant to establish a baseline using a range of light levels that would be typical indoors. But by no means was this meant as definitive – just a first foray into a topic that has surprisingly remained unexplored in a controlled way.

Also, as I point out, what is surprising is not so much the fact that some paints dried faster with more exposure to light, but that a full half of the samples dried just as well in complete darkness with no light or UV exposure. That runs counter to most expectations and there is no easy common connection between the pigments that would explain this behavior. So a lot to look at. But definitely as part of future rounds, we will be including sunlight, along with various types of other light sources (LED, halogen, incandescent, and blacklight). So stay tuned!

Interesting. But no direct sun data? What else I’ve always wondered over is the effect of heat and forced air… perhaps you’ve already done those studies?

The effect of direct sunlight would be interesting to see. Also, the question of different drying times for different pigments, how does that affect the paint film strength, and does it lead to eventual cracking of the paint surface when parts of the painting are drying faster than others? Should our goal be an even drying time of all different colours rather than a faster drying time?

Hi Brent –

Thanks for the comment and great questions! Empirically we know there are far fewer problems with different drying times in alla prima painting, where everything is applied in one sitting and dries all of a piece, versus the complications when layering paints on top of each other. However, your questions definitely point to areas that need more testing. Unfortunately, as you likely know, it can take years for cracking and any meaningful differences in film strength to show up, which makes test design a bit challenging. But will definitely add these questions to our list of ones to explore.

As to sunlight, as I mentioned in another comment, we did do some very limited testing in this area, and got some interesting results, but wanted to expand the scope before writing anything up. So look for that to be discussed in a future article.

interesting.

indirect bright indirect sunlight (either art studio indirect light or direct but reflected light) on the slower driers would be very interesting in the next study

Hi Ralf –

More than any other request for future testing, adding sunlight as a variable is on the top of the list. So you are not alone! Look for that area to be explored in more depth in future rounds. In the meantime, keep in mind that at least one site in these tests had a window not far from the wall, so at least some of the data involved samples with indirect sunlight as a component, and those dry times were in line with the others. But more needs to be done in this area to really see the impact of direct and indirect sunlight exposure.

Thank you very much for the experiment and for sharing it. In my personal experience I know that the paint on the canvas and the palette in summer dries much faster than winter. I already know that in summer there is more light, but I am referring to a room with artificial light where natural light is only a complement. Here the ambient temperature and the low humidity surely help. On the other hand when I want to preserve a palette with colors that I have pre-mixed because I need to suspend the painting session or protect some color to make corrections in the next few days in the painting, I cover my palette with PVC film and store it in the fridge. This works by combining less air through the pvc cover, darkness, low humidity and cold. Greeting.

Hi Leonardo –

Thanks for the comments. Definitely temperature should have an impact since heat will generally speed up chemical processes. And of course cold will slow things down. As a factor humidity is less clear since oils are not drying through evaporation, so the level of saturation of water vapor in the surrounding air should not have an impact. But of course in the real world it is hard to separate humidity from other factors like temperature, so it is usually difficult to separate out all the factors. Finally, while we know that many people will store their paints and palettes in a frig or even freezer, this is not something we can recommend or endorse as it places paint alongside food items. If wanting to do this regularly it would be best to have a dedicated small fridge for purely this use.

Thanks Sarah, the drying time of oil paint is a thorn in our side. In today’s world, painters have to contend with deadlines – something that painters of old were exempt from. I dislike using Liquin or other dryers, but more than once I have been tempted to speed drying time by raising the temperature. I know of one painter who dries his paintings by using a ‘reptile pad’ (an incubator-type-thing that is meant for snake cages). Surely a paint film that has dried in this way will lack the integrity of a film that has dried naturally?

Drying times and despair over it actually goes back quite a ways and is not just an affliction of the modern painter – although likely aggravated by our faster pace. If interested in some of the more immediate background on drier use in the 19th century, when cobalt and manganese driers come on the market, see Leslie Carlyle’s Paint Driers Discussed in 19th Century British Oil Painting Manuals:

In terms of your immediate question about the use of heat, it is true that temperature plays a role and heat will accelerate chemical processes in general. However we would suggest keeping temperatures within the normal reasonable range one might expect to encounter in, say, a non air-conditioned studio. Perhaps low 80’s? Even then, understand that heat accelerates everything – meaning both good and bad. For example, it can accelerate yellowing and embrittlement. Ultimately there is a good reason that researchers are skeptical that you can accelerate age an oil paint film because all the processes are so complex and interlinked that there is no way to accelerate all of them simultaneously. Because of that we always think it is better to age films naturally in well lit but still moderate conditions.

Thanks Sarah – Jeepers, the article you mentioned above (by Leslie Carlyle) is pretty scary. One can only hope that the alkyds we use today will fair better than the dryers of old. It is interesting that even in the 1800’s they already knew to apply the slow-drying over fast-drying rule:

“Artists also were advised to paint their first layer of paint (called the dead coloring) with fast-drying pigments exclusively…”

As you know, it has become common practice to execute one’s underpainting in alkyds, and then apply regular oil on top of this. Most pundits suggest this is acceptable, but perhaps you would consider undertaking a study on the intricacies and complications of underpainting? Just a hint. Thanks again for the great work.

Hi Alex – thanks for the compliment, and yes, Leslie Carlyle’s research can often be both a cautionary tale as well as a wonderful source of historical knowledge. The issue of alkyds, and in particular alkyd mediums and paints when used with or blended into oil paints, all need more research. And while we have things going, unfortunately any reliable results will take some time as issues usually take year and more likely decades to develop. Until then, we think the real key is simply to use one’s sense of keeping the applications modest, in terms of thickness, and keep any additions to just the minimal amount you need to achieve an effect. But then, that is good advice even when painting with oils alone.

I use regular (non boiled) linseed oil to protect steel. Preheating the steel to around 300 degrees C makes the oil finish dry, otherwise it would never dry.

Certainly, raw linseed oil by itself can take a long time to form a film. So yes, the high heat will definitely cause the oil to polymerize. In fact, that is the temperature Stand Oil is processed at, which is linseed heated in the absence of oxygen. In your case, with oxygen present and the film applied so thinly, the process should be quite fast I would think.

Sarah, please recuse what may seem like a “left field” question, but in my searches, you seem to be an expert on drying oils, and as such, may be able to speculate on a different application of same. I have recently started fabric dyeing (fiber reactive dyes on cotton), and my “wet” results pale significantly after washing/drying. I am beginning to experiment with applying drying oils, misted lightly, to restore the depth of color with hopes of also making articles more colorfast to laundering. I’ve started with a high linoleic safflower oil, detect little odor, and generally see the visual benefits I seek immediately. So my first question is a general one: Does this seem a reasonable application? If yes, then what aspects of drying time should be of concern? I assume there is little oil thickness so surface to volume should be very high…autoxidation should proceed quickly. Using safflower, yellowing should be low. I want to give treated items sufficient time to cross-link before laundering, but I don’t know if that is in hours, days, or weeks. Could you offer a speculative opinion? Thanks…

Hi Bob – Happy to help as best I can. The change in color and saturation is caused by the change in the refractive index of the medium surrounding the color as the water evaporates and gets replaced by air. It is something you can also see with river stones and seashells – those richly colored objects quickly become drab when pulled out from the water. Or is similar to the deepening and richness in color you see with wood when you put a clear polyurethane on it. Anyway, that’s just background on the mechanism and a way to confirm that what you are seeing is a well-known issue. The only way to restore the saturation would be to apply a gloss topcoat or finish to the dyed areas. Unfortunately, using drying oils will not be helpful for a few reasons. One, drying oil do really poorly in holding up to any degree of launderability and will degrade quickly when exposed to the dirt and wear of handling. So we would strongly recommend not going down that route. Also, it is not clear from the above if you are trying to coat the entire fabric or just an area, as that might make a difference. In the meantime, if you wanted to experiment, you could try some of the products we recommend in our tech sheet on Fabric Applications. Keep in mind that we have not done extensive testing using all the various techniques and dyes, so what follows is just sharing some ideas that may or may not get you the results you want. The best possible application would be to use an airbrush, to allow you to apply just a very light misting of GAC 900 as a form of clear coat that will help lock in the color, provide a slight sheen and increase the launderability. But you will need to follow the heat setting directions in the tech sheet. If you need something glossier, then you could try mixing 2 parts GAC 500 to 1 part High Flow Medium, then mixing that 1:1 with GAC 900. By changing the ratio of the mediums to the 900 you can get a range of softness and sheen. Anyway, its a place to start and depending on how things go we can guide you further from there. For additional feedback or questions, please send those to our general email address,[email protected] and one of the Materials Specialist would always be able to respond.

Hello,

I have found this experiment quite interesting. I was wondering how you were able to find information regarding the drying times of the different colors as well as which ones were reactive and inert pigments? I’ve tried to research myself but only come across in-depth scientific papers.

Hi Jennifer – Thanks for the comment and question. You are right that there is no good easily accessible article that lays out which pigments are inert or reactive, and of course, there are different types of reactivity, so not all pigment-oil interactions will impact drying. Case in point, zinc oxide is highly reactive in the presence of drying oil, causing the formation of metallic soaps and creation of a brittle paint film, but it is also extremely slow drying. So if interested purely in drying, finding listings of which pigments are fast or slow driers by nature will give you a rough proxy for which are which. Ralph Mayer provides a listing of the main ones, and discusses reactive and inert properties of various pigments, in his The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques. Also Mark Gottsegen’s The Artists’ Handbook would be a good resource. Unfortunately the drying time charts and ratings provided by manufacturers reflect the specific formulations being used, and the potential addition of driers when needed, so they do not necessarily give you insight into the pigments in and of themselves. That said, you can find our most updated chart for Williamsburg Oils here, and the categories do give a decent sense of which pigments are intrinsically faster drying, and which slow:

Drying Times Chart

Plus take a look at our article, Weighing in on the Drying of Oils for general information on how drying happens:

Weighing In on the Drying of Oils

Speaking very generally, the pigments that will dry faster generally contain cobalt, manganese, iron or copper components, which act as siccatives and help catalyze the oxidization of the oils. So cobalt and cerulean blue, manganese‑based colors like manganese violet, or colors that contain manganese like raw and burnt umber, copper-containing colors like the phthalos, or iron-based ones like prussian blue, have all proven to be faster drying.

I hope that helps some. Also, take a look at the Ralph Mayer and Gottsegen books and see if they don’t help as well.

Hello,

Thnx for providing the wealth of information in this website! I’m a painter located in Holland, and am at the moment looking into evening out the drying time of my oil paints by adding some slow drying oils (eg poppy). I want to find out the exact amount I have to add to get equal drying times for the pigments I use. I did a ‘pilot’ experiment, adding drops of poppy oil to a sample of paint, painting a patch, and then measuring the weight, adding another drop, weighing again etc., so I can calculate the exact weight ratio of added oil to paint for each patch. I then observed how the patches dry. This is where I kind of run into trouble. The paint is dry to the touch at a certain time, but there are a lot of stages inbetween fresh and dry to the touch. It would be interesting to have some way of measuring until which time the paint still is workable. At a certain time it becomes too tacky or too much set up. But how can one measure this systematically? Maybe you can help out.? Thnx

Hi Jos –

Would be happy to share our thoughts. The best way to get a systematic read on the state of dryingy might be to conduct drytime testing, along the lines that we did in our article Weighing in On the Drying of Oils The problem with that though is the need to cast paint onto polyester film so any weight gain is purely in the paint and not absorbed humidity and the use of a very accurate gram scale. Doing that will get you graphs like this

where you can start to separate out the stages a bit more.

Short of that type of research, you could test for what is considered ‘hard dry’ – where you would not be able to leave a mark in the surface of the paint with your fingernail. That stage does speak to a fully cured film that should be safe to paint on top of. In our own drytime tests, we cast precise 6 mil drawdowns and use cotton swaps to see if you can move the paint along one edge, doing it daily until you can no longer disturb the paint. Along the way you will see that you move from wet, to thick, to tearing a skin, to finally solid. We have never done a systematic capturing of each of those stages for each of our paints, and doing so would be a big job to say the least. And then too, a lot would depend on the environmental conditions, and not sure if the data there would speak accurately to the drytimes you would get on a more absorbent ground.

So, not sure if any of the above is helpful, but glad to keep thinking it through with you.

What a fantastic article! Thank you for sharing your work. There are, as you have mentioned many many more experiments and variations on experiments that could add to a greater indepth understanding of the effect of light on oil paint drying times. I would however like to suggest an entirely different line of questioning. Have you considered running tests on Oxygen absorbtion rates and drying? An oxygen saturation tent could be constructed relatively cheaply and safely, possibly by adding a fill and exhaust valve to the side of an actual “safe.” Just a thought. More oxygen would assumebly help the oils oxidize more quickly, but without testing it’s just a guess. And of course then testing using different saturation levels combined with different lighting levels would be in order. In my imagination, a painting could be “oxygen baked” overnight and be completely dry even with heavy imposto. Cheers and good luck experimenting.

Hi Cory –

Thanks so much for the warm compliments!! It is always wonderful to know that this type of research is valued by our readers. I know there is some testing that has been done roughly along these lines – or at least looking at the impact of different atmospheric composition on drying. For example, while you can’t get to all of this article publicly, you can at least see the first page:

Drying of Linseed Oil Paint Effect of Atmospheric Impurities on Rate of Oxygen Absorption

but nothing I know of looking specifically at thicker paint films. My own guess is that you might get more rapid skinning over of the paint, since that is where you would get the immediate absorption of oxygen and resulting crosslinking. However that skin would quickly act as a diffusion barrier to thee penetration of oxygen deeper down within the paint. It is not unlike the issue of drier levels, and why high levels of drier can actually slow up the curing of paint rather than speed it along. See the following article of ours on that:

Weighing In on the Drying of Oils

But that is not to say it wouldn’t be interesting to take a look at the issue of oxygen, with and without different types of light and temperatures. So many things to test, it turns out, even after 600 years!

Thanks again – and let us know if there is anything else we can ever help with.

Hello Sarah

I had an idea much like Cory had about creating an oxygen tent for drying oil paintings. I was thinking of a way to get the entire paint layer to dry more uniformly. I was thinking about going a step further. What about using a laser to create microscopic holes in the paint layers. My guess that this would increase the surface area and maybe get around the problem with the skin formation keeping the interior wet.

I read about laser being used to remove layer of varnish, could it it be used to help dry oils faster?

Hello Ross,

Sarah is still on her sabbatical which is why I am chiming in. Your idea is interesting, although micro-holes in fresh oil paint would probably ‘heal’ or close quickly. It would also be extremely time consuming and lasers have also been shown to cause oxidation and discoloration in pigments. In principle calcium auxiliary drier does the same thing- it keeps the film matrix open which allows more oxygen into the film and more solvent to escape early in the drying process.

Here are two link to related articles:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26488029_Laser_Cleaning_of_Easel_Paintings_An_Overview

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288029008_Principles_of_laser_cleaning_in_conservation

Warm regards,

Mirjam

It likely depends on the pigments used in the paint color. As we found in our testing, some pigments will contribute to drying while others slow down the process. Many manufacturers use driers in the oil paints that encourage drying, which can make it difficult to cross reference pigment tendencies from brand to brand….Water miscible oils also dry through oxidation of the oil binder, so depend on reactions that are encouraged by light and warm temps. You may be able to check with the brand you are using to see if they have a dry time chart for their colors.

Take care,

Greg