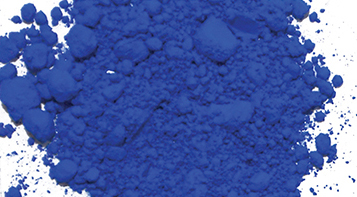

Ultramarine Blue stands, and has stood for a while, in fact for years, decades, centuries, as a pillar unbroken, unmovable, not fazed by its position or status. Ultramarine Blue has enjoyed a prominent position in palettes that span from sixth and seventh century A.D. into the contemporary palette of our new QoR® Watercolor line. Such ubiquity can go unnoticed and can feel commonplace when it exists in every palette although when eyes are cast upon its full watercolor tone the mind travels to deep seas, the sky before dawn and ancient tombs. Watercolor, due to its dry finish, delivers Ultramarine Blue in a way that keeps the color as lively as the dry pigment and does not darken or dull its brilliance. The first known use of Ultramarine Blue was in wall paintings in the cave temples at Bamiyan in Afghanistan and adorned the backgrounds of the painted buddhas. These paintings were geographically very close to Sar-e-sang, the area where the blue veins of the mineral, Lapis Lazuli, were extracted.

Ultramarine Blue stands, and has stood for a while, in fact for years, decades, centuries, as a pillar unbroken, unmovable, not fazed by its position or status. Ultramarine Blue has enjoyed a prominent position in palettes that span from sixth and seventh century A.D. into the contemporary palette of our new QoR® Watercolor line. Such ubiquity can go unnoticed and can feel commonplace when it exists in every palette although when eyes are cast upon its full watercolor tone the mind travels to deep seas, the sky before dawn and ancient tombs. Watercolor, due to its dry finish, delivers Ultramarine Blue in a way that keeps the color as lively as the dry pigment and does not darken or dull its brilliance. The first known use of Ultramarine Blue was in wall paintings in the cave temples at Bamiyan in Afghanistan and adorned the backgrounds of the painted buddhas. These paintings were geographically very close to Sar-e-sang, the area where the blue veins of the mineral, Lapis Lazuli, were extracted.

The color itself, its preciousness, rarity and brilliance directly assigned the rank of religious characters in religious themed paintings. During the Renaissance the colors that were most difficult to extract, obtain and the most expensive were at that particular time reserved for the most revered. It is for this reason that the Virgin Mary is always enrobed in sacré bleu. At the time, Ultramarine Blue was not simply part of the artists’ palette due to its price but was ordered by the patron when the painting was commissioned. This could account for Mary missing in some unfinished paintings. Ultramarine Blue has been found in Chinese paintings, Persian miniatures, Indian murals, Italian religious panels to illuminated manuscripts.

Once extracted from the earth, Lapis Lazuli was ground and mixed with molten wax, resins and oils, wrapped in a cloth and kneaded under lye which released blue particles that separated themselves from the rest of the mixture. Unfortunately, simply grinding the mineral yielded a pale, almost colorless pigment.

What we use today, what we call Ultramarine Blue is chemically similar to Lapis Lazuli. Initially discovered by Goethe as blue deposits on the walls of the lime kilns near Palermo, Italy and again years later by Tassert in the soda kilns of a glass factory in Saint Gobin, France, a chemical analysis revealed great similarities and spawned a contest for a synthetic and inexpensive Ultramarine Blue. In 1828 the monetary prize was awarded to Guimet who perfected making the pigment for 400 francs per pound as opposed to the 3,000-5,000 francs per pound that genuine Lapis Lazuli commanded.

Ultramarine Blue is a polysulfide of sodium-alumino-silicate. Its ingredients are sodium, aluminum, sulfur and silicon dioxide and the materials used for manufacture include anhydrous sodium sulfate or carbonate, china clay, fine sand and sulfur. The ingredients must be iron free and pure to facilitate the process and color. The ingredients are heated for hours in crucibles in an air free environment producing a green color. It is then ground, washed and reheated to reveal its blue color. Different processes for production exist that alter time and temperature to yield color with one heating. The ratios and grades of silica and sulfur directly affect the reactivity of Ultramarine Blue with acids.

Ultramarine Blue particles that are large in size will yield a deeper blue color, smaller particles will offer greater tinting strength. The pigment particles are a round, regular shape and size as opposed to natural Lapis Lazuli which is much larger, irregular and more transparent. Synthetic Ultramarine Blue particles appear opaque although the refractive index of the natural and synthetic do not differ greatly.

Ultramarine Blue has excellent lightfastness, although exposure to acids (especially sulfur dioxide and acidic fumes of urban areas) causes Ultramarine Blue to fade and therefore, its use in exterior murals should be avoided. Its transparency and matte sheen parade its depth of color and richness into palettes the world over. It has on countless occasions mixed beautifully with others to expand ones palette exponentially, becoming a necessity in its ubiquity under and within every sky.

About Amy McKinnon

View all posts by Amy McKinnon -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

Although I paint with acrylics, not watercolour I can say that Golden’s ultramarine blue is the best. I tried other brands and they were not the right colour. I specialize in underwater paintings.