The Material Specialists here at Golden Artist Colors are often requested by artists to diagnose the reasoning for problems occurring in their paintings based solely upon their words used to guide us. One of the most common emails or calls require the understanding of whether the artist is discussing a crack versus a craze in the paint film, and exactly what shape the crack or craze is. Both of these conditions are caused by a similar mechanism of reducing stress in the paint layer. Often these stresses are built up during the drying process yet some cracks may only appear with some other mechanical and / or environmental stress in the future. Understanding the causes of these fractures in the paint film will both allow for corrective action or point the artist in a way to take advantage of what might be to others, a paint defect.

What the Heck is a “Craze”?

A craze is typically considered a surface defect, developing most often in acrylic paints or mediums that when applied, begin to form a skin while the material underneath is still fluid and wet. The very flexible acrylic film can usually stretch quite easily as the edges of the skin begin to dry, requiring the center of the film to continue to stretch as water evaporates and the film shrinks. In some cases, the center areas of the drying film can no longer take the stress of shrinking and a tear in the upper part of the film occurs. This then leads to a phenomenon where water and other volatiles are more able to be released from this area of the tear. It’s sort of like lifting the cover off a boiling pot to one side; all of the evaporative pressure is now targeted at this area of the film. Sometimes this tear can reach all the way down to the paint layers below, but even more often the surface film repairs itself, yet left with the scar of the original tear and still noticeable on the surface. Although a craze is a physical surface depression, it does not pose any long-term stability issues to the painting. The film formation process has not been compromised.

At times the crazing phenomena can occur in very thin films. More often than not, this sort of crazed surface is the result of the lack of a coating being able to wet out the layer below. So as the stresses caused by the evaporation of water continue, areas where the cohesive force of the acrylic film is greater than it’s attraction to the substrate or paint layer below, you begin to see these same crevices in the film. In extreme circumstances this crazing can actually leave breaks in the film.

Products which do not relax or flow after being applied to a surface do not have the same issue of crazing when applied. For example, Soft Gel, Heavy Body Acrylics, and Molding Paste are artist materials that are highly unlikely to craze even when applied generously to a canvas. The shrinking product’s structure remains stable during drying. One can overcome this by adding a generous amount of water to these products. The additional water simply increases the amount of shrinking that will occur in the drying process and therefore increase the stresses in the film.

When is the Defect Defined as a “Crack”?

Cracks are also the material’s way to relieve stress. They can be identified by their crisp breaks. The sharp-edged individual pieces are defined as “platelets”. Some cracks occur when a hard, rigid paint layer is flexed further than it is physically capable of bending. These cracks run deeply throughout the entire painting. When decades-old oil paintings on linen are carelessly removed from their stretchers and rolled up tightly they are probably going to crack severely. Even acrylic paints, primers and gel mediums can crack. Acrylics are thermoplastic and when they are in cold climates they become increasingly stiffer. When they are rolled or unrolled in the wrong temperature they can crack, even if they exhibit no issues in warmer room temperatures.

Another reason paint layers may crack is because the underlying materials are swelling up, pushing against the less elastic layer. At some point the stiffer paint has to give, and it creates a cracked surface. Exterior grade housepaints are formulated with a high degree of elasticity in order to reduce the cracking that occurs when the underlying wood swells from moisture.

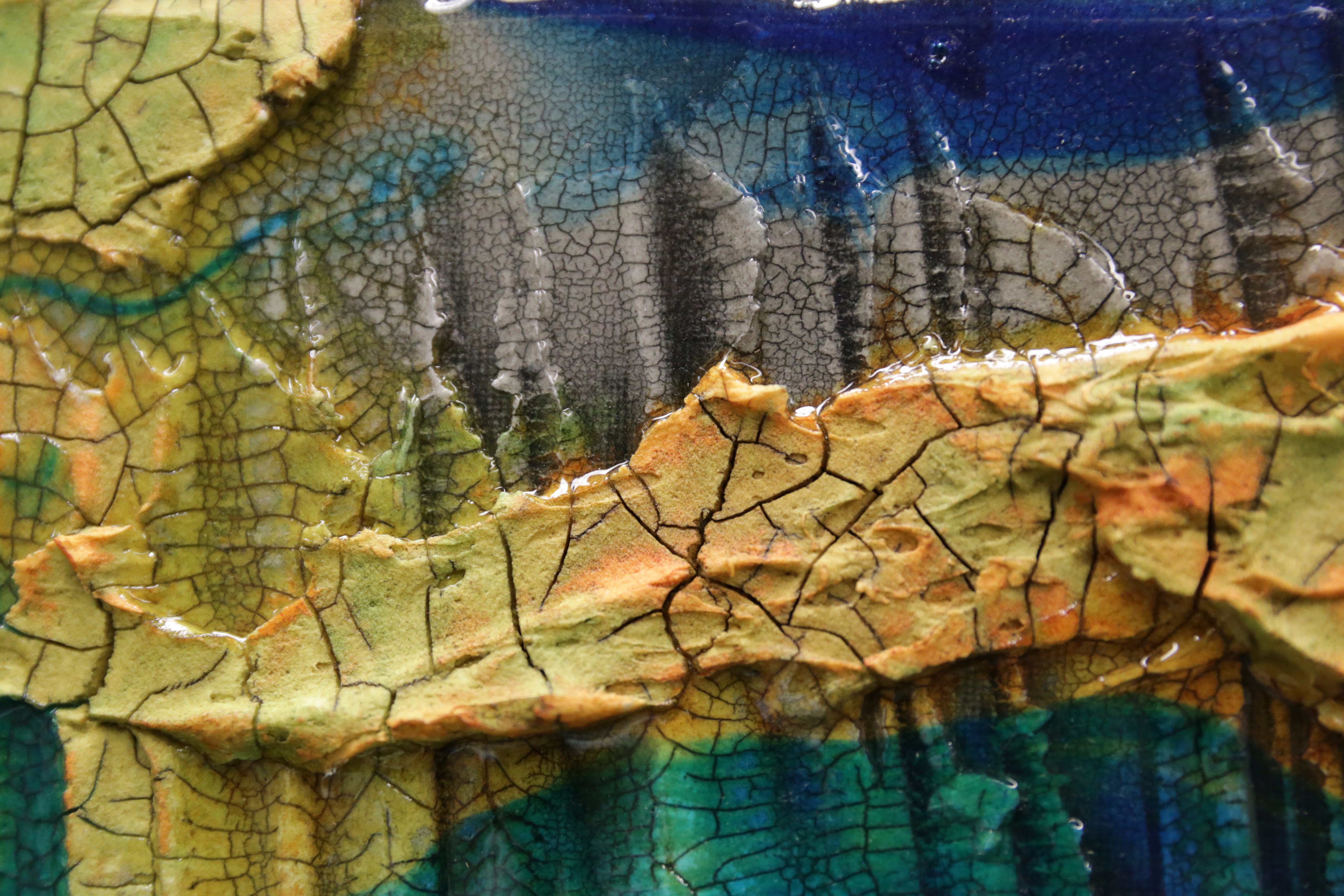

Some artist materials crack due to their formulation. When a product is overloaded with “solids” such as marble dust, it becomes more than the binder system can handle. The shrinking film tries to stay intact, but must yield at some point, and again, cracks are a result. This cracking resulting from a material being under-bound is observed in nature when a riverbed or lakebed dries up. The mud cracks, forming deep fissures. This phenomenon is the reason our Crackle Paste works. It relies on being under-bound just enough to develop a cracked (also known as crackle) layer. Of course, we have to be very careful as to modify the solids to binder level just enough to cause the pattern to develop, and still be stable enough for use within artwork. Proper surface preparation and sealing the surface after the cracks are done developing are paramount to long term stability.

In the Ceramics Industry crazes and crackles are both defects and decorative. They often are the result of the glaze recipe or the speed of the cooling off cycle after firing the pottery. The pattern develops as a means to reduce stress or tension within the coating. Craquelure is used to define a large or complete area of fine line patterns.

Unintentional cracking or crazing often happen during the painting process when the artist least expects it. Some are the result of applying a paint, gel or medium a bit too generously, and others happen because external factors such as temperature, humidity and air flow are not taken into account. Even if an artist has used a product successfully for years, defects can occur. When troubleshooting, consider the impact of the immediate environment and changes in the weather. What worked perfect in the summer may not work at all during the winter months.

Crazes can be minimized through careful planning and control of the product application and studio environment. While it’s near impossible to completely eliminate crazes from developing, one can greatly reduce their occurrence by:

• Working in a room temperature environment with little air movement, especially during the initial drying phase.

• Applying products thinly and avoiding thick puddles or dammed sections.

• Working on a flat, level surface.

• Avoiding movement of the work until it has cured, ideally leaving it alone for 3 or more days.

• Allowing underlying paints and primers to fully cure.

• Sealing the absorbency of the surface before applying a poured layer.

• Suspending a lightweight board such as Gatorfoam® just above the surface of the freshly applied medium to create a terrarium-like environment that slows the drying time down.

Take note of when crazes or cracks develop in your own work. Look at all of the factors present and narrow down the most likely factors that resulted in the defects and conduct tests to see if you can mitigate their development. The product you applied may be the wrong product for your desired application. If you are not able to figure out what’s going on, contact us so we can help you identify the problem.