By Michael Townsend

Over the last few years we at Golden Artist Colors have been hearing from more and more photographers who are experimenting with fine art materials. Through our conversations we began to learn about some new trends in photography. We were fortunate that three professional artists, that we have been working with, were willing to share their very different take on these trends. Tim O’Neill, publisher for Digital Paint Magazine and portrait photographer/artist; Marc Joseph Berg, artist and core faculty at the School of Visual Arts in New York; and Stephanie Farr, a Los Angeles-based fine artist and commercial photographer.

“…fashion photography was me trying to be practical and make a living and fashion is what I fell into because it seemed to have the most leeway as far as creativity was concerned.” Photographer/artist Stephanie Farr’s career as a fashion photographer was successful, but not satisfying. She wanted more, she wanted to explore her processes her way and she’s been doing just that for the last several years.

“I see myself as an artist. It just so happens that photography is my most highly developed tool. We live in an era where the world is shrinking and boundaries are dissolving. It’s not just painting or just drawing or just ceramics or just photography anymore. It can be everything at once. I feel the more tools I have at my disposal, the more poignantly I can explore the layers of meaning in the subject matter of a piece.”

Artist and core faculty at the School of Visual Arts, Marc Joseph Berg has also been seeking to push against the boundaries of traditional methods of photography. “I’m based in New York City where there’s an awful lot of art to look at so I’m constantly inspired by what I see going on around me. And I sort of felt like I was reaching a bit of a saturation point with the materials I had been working with.” As he began searching for new areas of exploration, he became intrigued with the idea of incorporating acrylics, as it required wrestling with different issues during the process. “… quite simply, the idea of getting my hands dirty and sort of seeing where that goes.”

For photographer/artist Tim O’Neill, mixing the mediums of photography and fine art has been a part of his working style as a portrait artist. His process relies upon post-manipulation. “Once we print the piece, that becomes the underpainting and then we do one more step or a few more steps after that.” The desire to push the boundaries further stemmed from the “need to separate myself from not only the new folks coming in, but other professionals that have been around for a while as well.”

For photographers attempting to achieve that individual distinction, the chemically infused darkroom was the development tool of the past. Today the digital studio is the photographer’s primary tool for customization, once the image has been captured in the camera. Images can be manipulated in the digital darkroom in so many ways. In fact these days it would be hard pressed to find a professional image that hasn’t been digitally altered and tweaked in some form or another. Yet even with all the creative options offered by software programs such as Adobe® Photoshop®, the reality is that the image is still — for the most part — printed on commercially-prepared papers and canvases designed for printing. The substrates currently available for the photographer are typically ones developed from decades of refinement.

“Photography materials traditionally are somewhat industrial and prefabricated,” Marc Joseph Berg explains. “Of course I don’t mean that disparagingly, it’s just that there are certain limitations to those surfaces.” Tim O’Neill had been feeling the same limitations, “I always wanted to be able to print on handmade paper or rag paper — anything that you could put through the printer.”

For Stephanie Farr the concern with digital photography and printing was that the ‘the hand’ was becoming too far removed from the process. “This is one of the reasons I began exploring alternative processes in the first place. I wanted to be more invested in the final product. The click of the shutter was merely the genesis of a dialog I desperately wanted to last longer than 1/30th of a second.”

For all three photographers, the discovery of GOLDEN Digital Grounds has allowed them to explore new areas, as well as resolve issues with processes attempted in the past. As with other photographers who have begun using the Digital Grounds, the ability to get back involved in the process is intriguing.

From Tim O’Neill’s perspective, “An artist can now find their own materials, anything that can be run through the printer — and put their hand to it. There are times when you want a very specific paper or substrate in order to create a specific effect and you can’t get it. … Now if I go to the art store and I see something that catches my eye, I go ahead and buy it. Before I was like, ‘Oh, that’s really cool but there’s no way I can ever print on it.’ Now I can go ahead and get it because I know one way or the other I can make a print on a new surface.”

A photograph can now be paired up with a substrate to better convey the meaning of the image. Even acrylic paints and gel mediums are potential substrates to print upon. Stephanie Farr worked through several processes before deciding to use GOLDEN Digital Grounds.

“When I first began experimenting with alternative photographic processes, developing a way to create transparent image layers was a priority. I’d worked in the past with the Polaroid® transfer process, which does result in a transparent image that is able to be manipulated, but they are small, very fragile, and expensive. (The average size of her work is four foot by six foot). After seeing a demo where a collage artist had used GOLDEN Acrylic Gel (using an indirect transfer technique) to lift the ink off a small black and white photocopy, I knew I had found the answer. The image gels that I now create can be applied to almost any surface. They allow me control over size, they are fairly durable, and it also allows me to incorporate color. The only drawback to the way I was doing it before, lifting the ink with the gels was that the ink was always on the bottom, underneath several layers of gel, which restricts my ability to control the clarity of the image. I was immediately drawn to Digital Ground because it works better than any other liquid emulsion I’ve tried — I have experimented quite a bit — because it brings the image up to the surface.”

Whether photographer or fine artist, anyone embarking on this area of exploration is going to encounter a learning curve. The photographer not familiar with artist products in particular, has even more to learn about working with ink-receptive grounds, creating substrates, and using artist materials.

Marc Joseph Berg puts it in wonderful perspective. “For me this is still very much in its infancy in terms of my practice. It’s super interesting, extremely exciting, but also terrifying in some ways. But, you know, I sort of see all that as being part of the process. I mean, you sort of go where you’re going and there’s not really much that I can do about where my interests are taking me sometimes.”

Tim O’Neill adds, “There are so many different avenues to approach and go down that maybe someone hasn’t gone down before. That’s one of the really interesting things about the technology that’s available to us today is the combination of various things, there are so many combinations out there that you have a really good shot of getting into something new. Go down a path that no one has been before and you may end up being a market leader in that. Having said that, there are probably 100 of those paths you’ll go down and they don’t produce the results you’re looking for. However, eventually you will find one where you’ll say, ‘Oh, okay, I think we have something here.’ The point is, there’s a whole new wide open playing field that absolutely did not exist before and it’s open for anybody. Furthermore, it’s a lot less expensive to play and to experiment than it was even just two or three years ago.”

Using the Digital Grounds allows these photographers to break into new territory. There have been ways to add images into paintings, and paint onto images, but now the lines are beginning to blur and past rules are being broken. At a minimum, the use of unique substrates can give the photographer the sense of having their hand back into the process. “Now we can go in, we can paint it, we can tweak things around that way and we can print it on a rice paper or we can print it on papyrus or we can print it on bark if we want,” said Tim O’Neill.

As shared by Stephanie Farr, “the novelty of the photograph itself has begun to wear off, allowing those of us who are inexplicably drawn to the viewfinder, to reach beyond. As an artist, you dedicate your life to exploring the work of those who have gone before you, and with that knowledge, you then strive to move art forward. I have merely tried to learn from what the masters before me have achieved while taking stock of current possibilities. With this in mind, I choose the pieces and methods that I feel will best help me answer the questions I have to ask.”

Over the last two decades the number of artists and photographers asking us for help with this process has steadily increased. The Digital Grounds have now allowed the GOLDEN Technical Services Department to explore an even greater array of products and combinations of techniques and materials. For us here at GOLDEN, we continue to learn about these materials, just like we still do with our other acrylic products. The process never ends, and we will continue to engage with artists to discover new uses and what new products need to be developed next. With the help of photographer/artists like Tim O’Neill, Marc Joseph Berg & Stephanie Farr, we are all learning new solutions and processes together. Marc Joseph Berg summed up all of the thoughts nicely by saying, “I’m sure you guys are aware that the possibilities are truly endless and I’m sure it’ll be very interesting to see how people are going to be using these materials.”

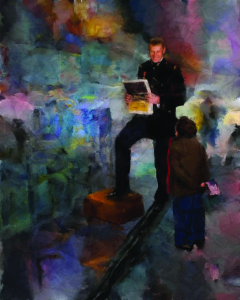

Marc Joseph Berg

Marc Joseph Berg

Marc Joseph Berg was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and attended Kent State University. Several one-person exhibitions of his pictures have been mounted in the United States and Europe. He lives and works in New York City, where he also teaches at the School of Visual Arts.

Stephanie Farr

Stephanie Farr

Originally raised in Missouri, Stephanie Farr has been learning and practicing her medium in Los Angeles for the last eight years. After receiving a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Missouri, she sought out a more technical knowledge of the camera, and decided to attend Brooks Institute of Photography where she was the head of her class, receiving the Outstanding Achievement Award. Next she secured an internship with a fashion photographer, learning how to produce shoots, manage archives, and find clients. After absorbing as much as she could, she began her own studio, producing images used by companies in the likes of Universal® and Avon®. Four years ago, she left the commercial world behind and began dedicating herself completely and entirely to her artistic work.

Tim O’Neill

Tim O’Neill

Nebraska portrait artist Tim O’Neill began his career as an artist and photographer working in a darkroom lab and processing film for a local company in his high school years. There have been many different directions of study in fine art, photography and business that he has pursued since. The digital revolution found its way to his studio in 2002 and breathed new life into his portrait art. Commissioned mixed media portraits are becoming more and more prevalent with discriminating clients. He is a self employed entrepreneur creating art, growing his brand, as well as teaching business and marketing skills to artists in online and offline workshops and seminars. Current passionate pursuit is building his online businesses, painting commissioned portraits and fine art pieces.

About Michael Townsend

View all posts by Michael Townsend -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post