egg tempera, acrylic, encaustic, and oil.

Mention a well-known pigment like Ultramarine or Cobalt Blue, and we instantly picture a very particular and unwavering color. And why not – it is easy to think of pigments as having characteristics that remain constant as one moves between different mediums such as acrylics, oils or watercolors. Even if we accept that the handling properties or the pigment load changes, certainly the color is constant, no? In this article we explore the surprising answer to that question and examine some of the ways a pigment’s color changes when used in different systems.

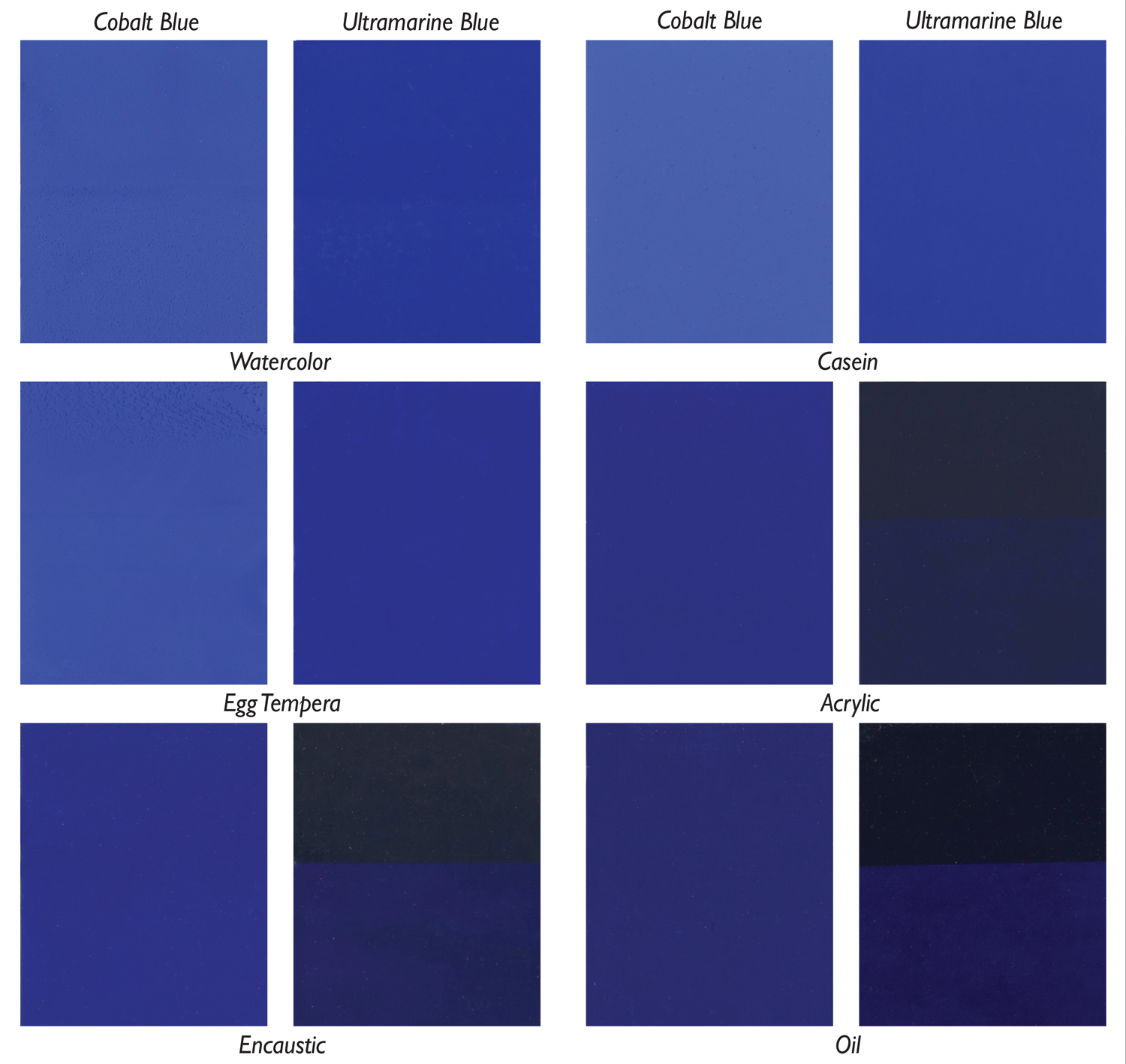

But first, a little background on how this theme came about. Every year Golden Artist Colors, along with other manufacturers, helps to organize and participate in a Materials Panel at the College Art Association (CAA). This last year the theme, “Pigments in a Bind(er)”, looked at the impact of different binders on the appearance of pigments. Working in collaboration with R&F Encaustics, Gamblin Artist Colors, and Natural™ Pigments, samples were generated using identical pigments of Ultramarine and Cobalt Blue prepared in egg tempera, watercolor, casein, encaustic, acrylic, and oil. No fillers were used, allowing them to represent as much as possible the interaction of pigment and binder alone. These were cast on black and white drawdown cards at similar film thicknesses then cut into 2”x 3” swatches and carefully assembled on a display board (Image 1). What follows is adapted from our presentation, which focused on the role of pigment load in the appearance and film qualities of these very different paints.

Constants

Certain aspects of a pigment are considered constant, such as the molecular weight, refractive index, density, and chemical composition. Very little that we ever do as paint makers or artists will change any of those things. Absent from that list, however, is the one thing we almost always think of when referring to a particular pigment – its color. So the question is a simple one: why? Why do some of the swatches, all using the same pigment, look so different from each other? As we can see in Image 1, our panel of two pigments in six binders roughly breaks into two groupings with very distinct appearances. In one group you have watercolor, casein, and egg tempera, where the colors are brighter, higher chroma, and more opaque, especially with Ultramarine Blue. In the others (acrylic, encaustic, and oil), the colors grow deeper, redder, and with Ultramarine Blue in particular, considerably more translucent.

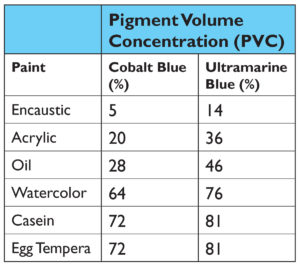

One would typically think that the Refractive Index (RI) of the binders would be the culprit, but while this can sometimes be a crucial factor, in this case the data simply does not support that common theory. There clearly is not a broad enough range to account for the sharp differences (Table 1i).

Pigment Volume Concentration (PVC)

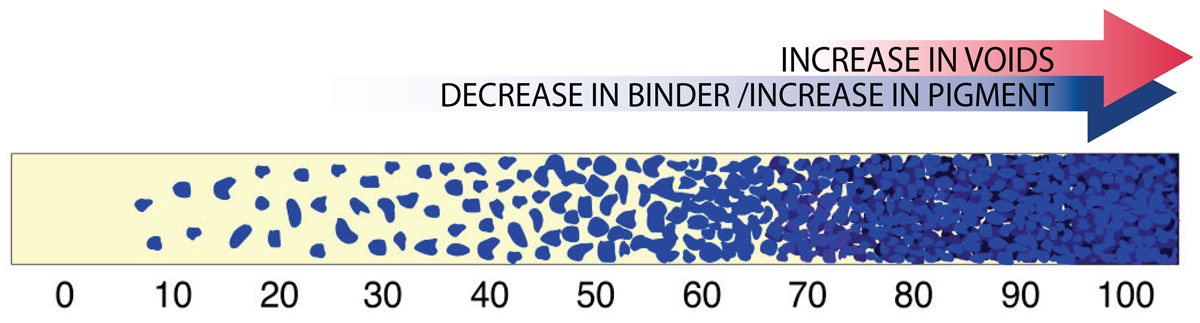

Looking past refractive index as a main cause, a more promising possibility is that the changes are driven by differences in the Pigment Volume Concentration (PVC), defined as the ratio of the volume of the pigment divided by the volume of both pigment and binder together:

PVC = pigment volume / (pigment volume + binder volume)

This represents the percentage of pigment in the paint layer after everything has fully dried and is what most people think of when talking about ‘pigment load’. And sure enough, if we look at the paints that were made, the division we noticed between the visual appearance of casein, watercolor, and egg tempera vs. oil, acrylic, and encaustic is clearly echoed by the sharp increase in the percentage of pigment in each of the dried films (Table 2).

Critical Pigment Volume Concentration (CPVC)

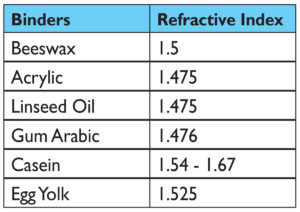

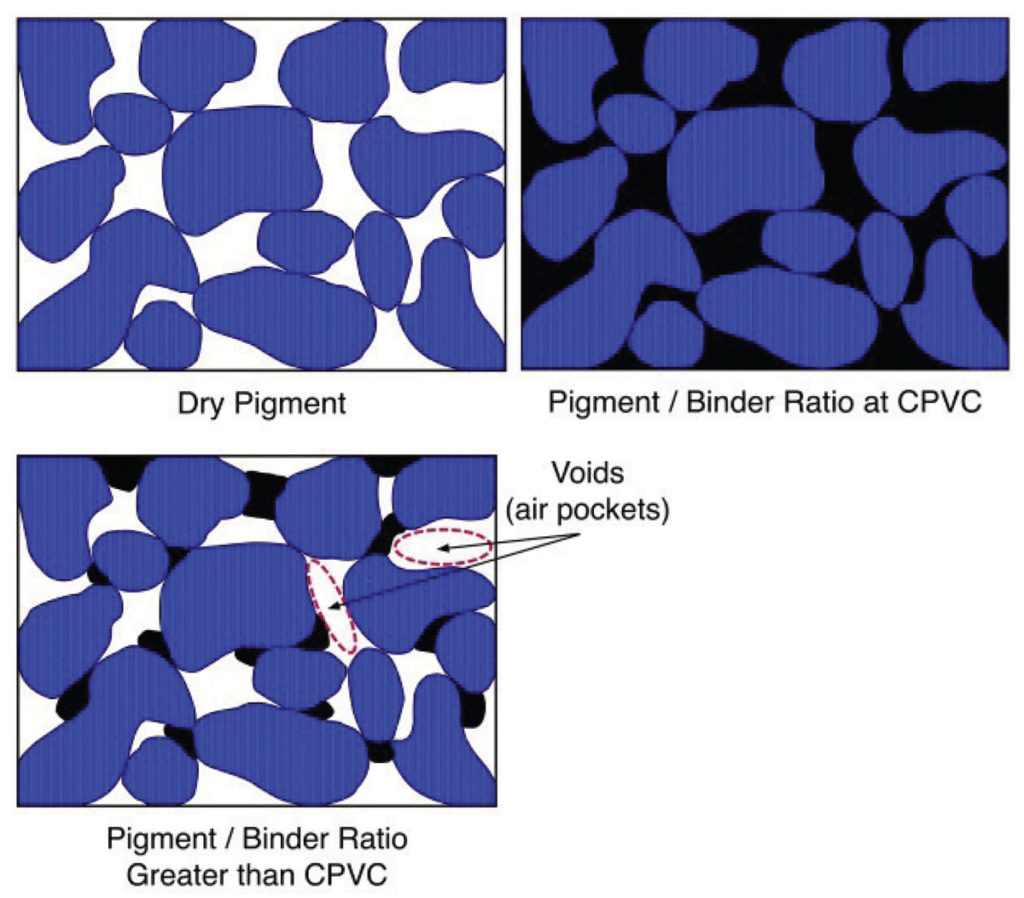

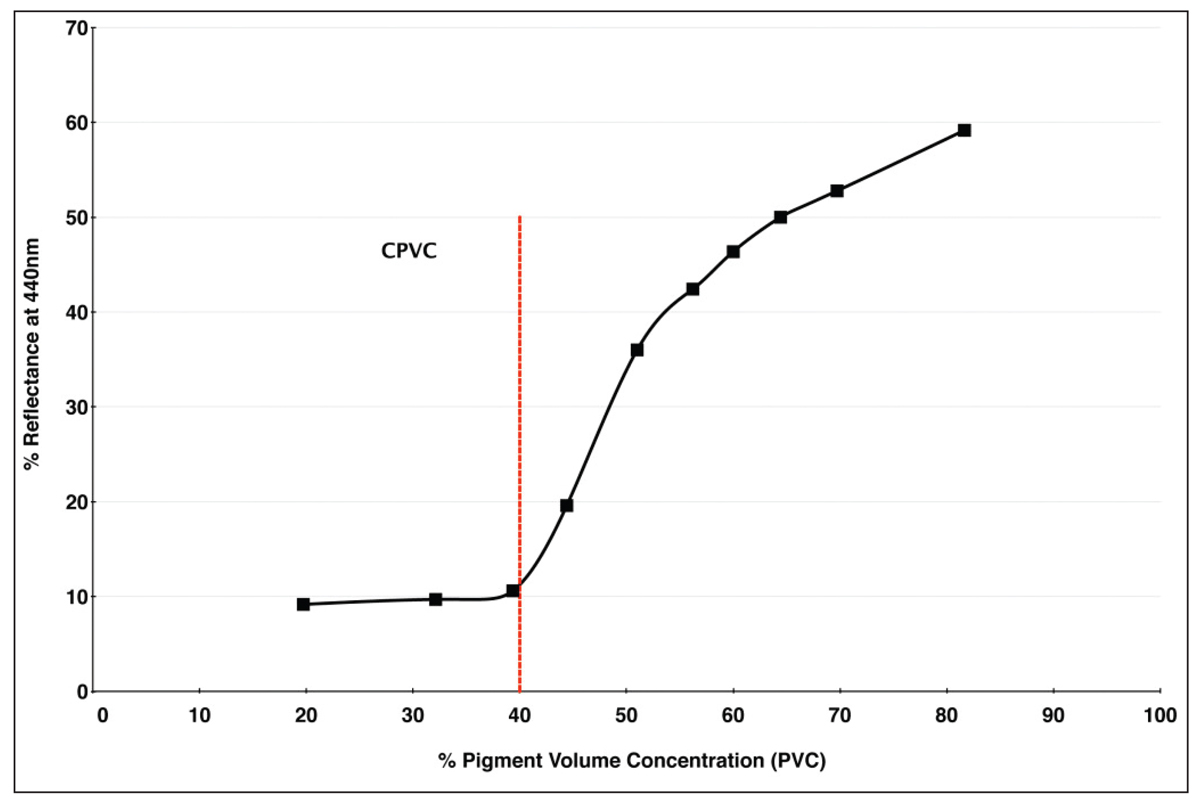

As the ratio of binder to pigment changes, one reaches a sweet spot where the pigment is at its maximum loading while still having all the air between the particles completely filled with binder. This optimal point is known as the Critical Pigment Volume Concentration, or CPVC. While every paint system will be different, the CPVC generally falls somewhere in the 30-60% range. As one moves along this continuum (Image 2), and past the CPVC, one moves towards a paint film that has an increasingly large number of voids, which in turn leads to a layer that is more matte, more permeable, and increasingly fragile.

Looking at these stages more diagrammatically, if we were to peer inside a paint film at different stages, we would see something similar to the following contrast between a starting point of dry pigment alone, a paint film at CPVC, and one that is well above that level (Image 3).

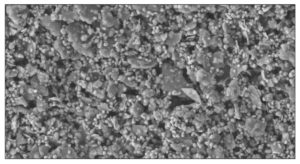

The actual surface of a paint film above CPVC, with a 60% pigment volume ratio, is dramatically captured in the following electron micrograph (Image 4).

As the surface texture changes, the appearance of the paint can change dramatically as well, as we saw in the contrasting samples shown earlier.

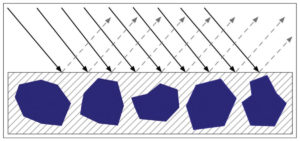

When paints are at or below CPVC, their smoother surfaces scatter less light, allowing more of it to penetrate and be absorbed by the pigment. As a result, the color will feel more saturated and deeper in value, as well as typically appearing more transparent since the difference in the refractive index between the pigment and binder is far less than the pigment and air. A smoother, glossy surface also reflects light away from the viewer in a more orderly, controlled manner. While one might occasionally get a sense of a highlight or patch of glare, one almost never sees the type of diffuse scattering associated with matte surfaces (Image 5).

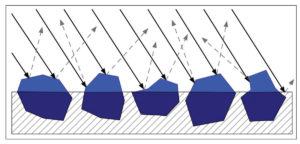

As a paint film climbs above CPVC it becomes increasingly matte and textured until, if pushed far enough, the pigments become underbound and only partly held in or coated by the binder. At this point the pigment scatters light to a far greater degree, since there is a much wider difference between the pigment’s refractive index and that of the surrounding air. In addition, the rougher surface scatters light in a far more random pattern, and this haze of white, diffused light appears to blend with the color of the pigment, causing it to seem lighter and often chalky or washed out by comparison (Image 6).

Lastly, the overall scattering is affected by the number of voids or air pockets found within the paint as these will scatter additional light that happens to penetrate below the surface, causing the color to appear quite opaque as a result; the internal haze of light acting like a form of interior fog that blocks any ability to see the surface below.

Robert Feller, a major figure in conservation science, happened to illustrate many of these changes in appearance in 1981 by measuring the surface reflectance of Ultramarine Blue paint formulated at an ever increasing PVC. Readings were taken at 440nm, which is the wavelength of maximum reflectance when this pigment is fully encased in a binder (Image 7).

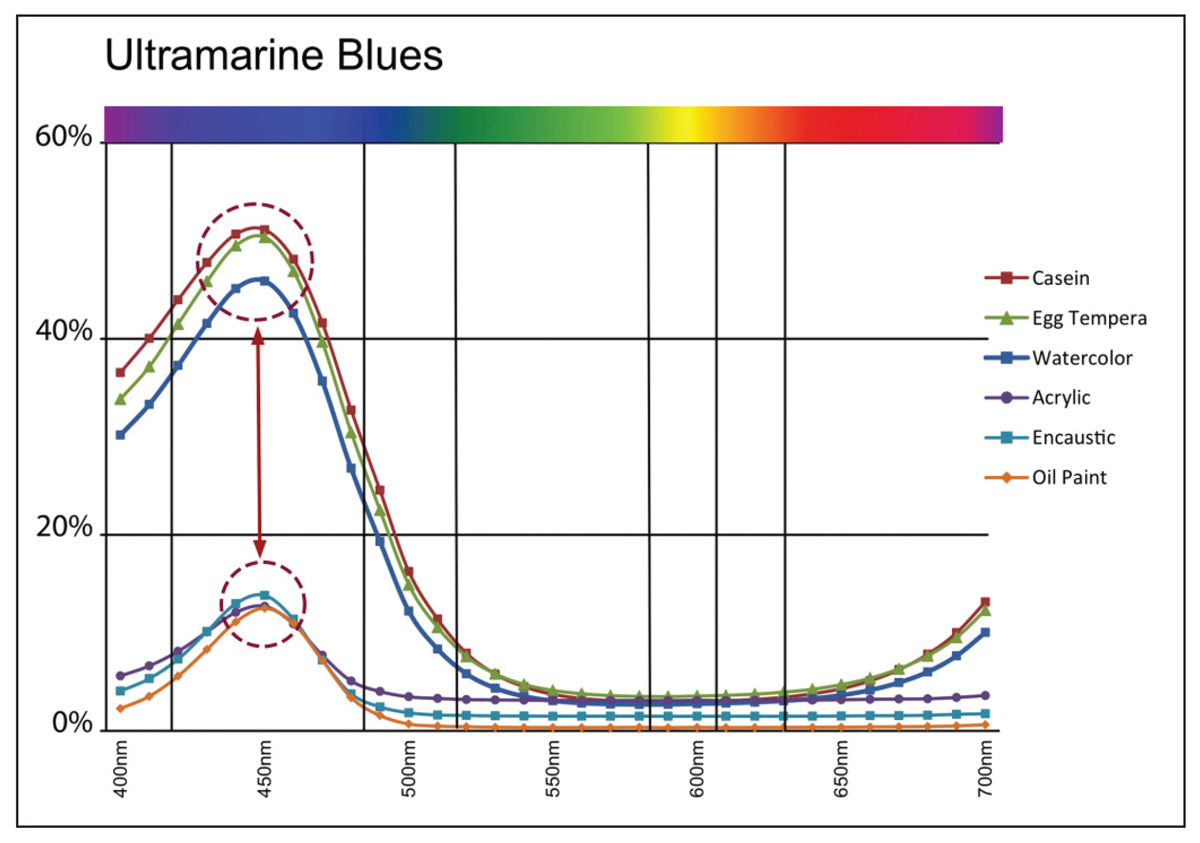

As you can see, as the pigment volume ratio crosses the CPVC mark of 40%, there is a sudden and quite dramatic increase in the amount of light that is reflected from the surface, going from a mere 10% to nearly 60% by the time 80% PVC is reached. If we now look at the spectral reflectance curves from our six swatches of Ultramarine Blue, we see a similar uptick at the 440nm mark. Here the three paints with PVCs running from 14-46% (oil, acrylic, and encaustic) indeed top out a little above 10% reflectance, while the three systems with PVCs running from 76-81% (watercolor, egg tempera, and casein) reaches reflectance levels of 50% or more (Image 8).

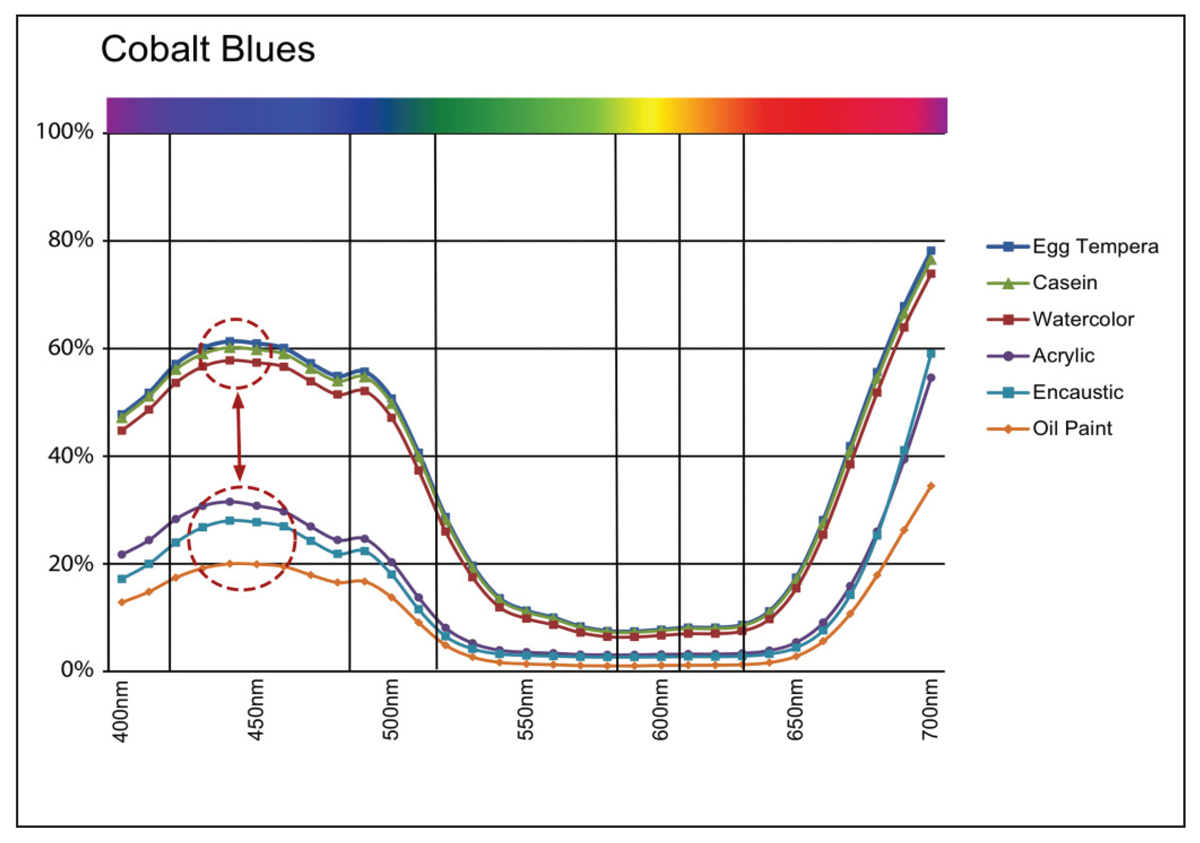

While Cobalt Blue is clearly a different pigment, with a very different spectral reflectance and refractive index, we can still see a similar pattern, albeit not quite as dramatic (Image 9).

While there can be little doubt that Pigment Volume Concentration impacts the ultimate appearance of a color, there are other differences that need to be looked at and which can be easily overlooked. To do that, we looked at three paints in our study – casein, acrylic and oil – and unpack the implications of their different PVC ratios, especially given their very different formulations.

Cobalt Blue

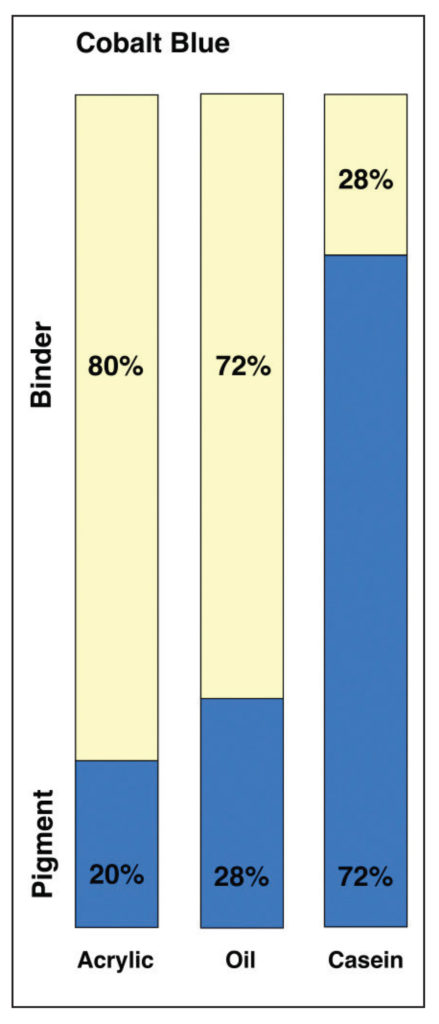

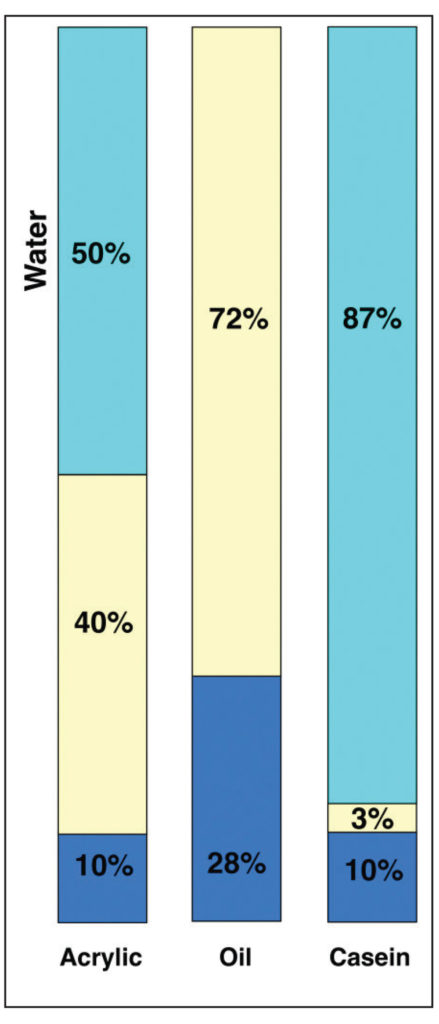

If we take the PVC ratios of dried paint films for Cobalt Blue in acrylic, oil and casein, we get the following diagram showing the relative amounts of pigment to binder for each system (Image 10).

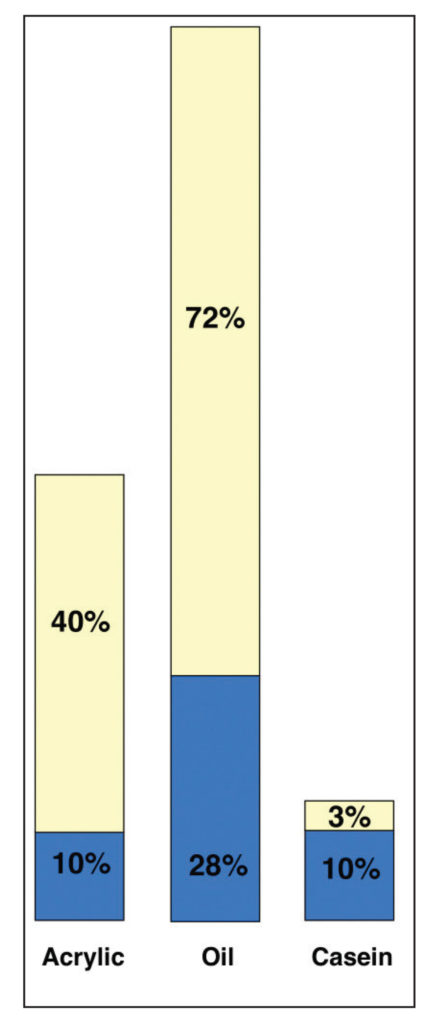

In this view, acrylics and oil do not appear wildly different, even if oil does have a PVC that is 8% higher. However, when placed next to Casein, which has an incredibly high pigment load of 72%, that difference seems to pale by comparison. However, focusing on these numbers alone can give a somewhat misleading sense of the systems as a whole. To do that, we need to add back in the one large component that is missing – namely the water found in both acrylic and casein – while keeping in mind that oils, by their nature, are a 100% solids system with nothing that evaporates away. This leads to a very different picture (Image 11).

This is a very different type of comparison and one that points to important issues masked by the broader, simpler PVC ratios when taken in isolation. All of a sudden one can see that acrylic and casein have similar percentages of pigment when compared to their overall systems (10%), and because water is necessary in their formulations, there is no practical way they can ever match the 28% pigment load of Cobalt Blue in oils. Thus the very real and frequent sense that oils possess a density that is unique and unrivaled, and that goes directly to not only the nature of oil and pigment when milled together, and the fact that oil molecules are exceedingly small and very efficient at wetting out pigments, but the sheer fact that nothing evaporates or leaves the film. Acrylics, and other water borne media by contrast, must always contend with having to accommodate a large percentage of water in their formulations. So, even when the final pigment to binder ratios might be close, as with Cobalt Blue in acrylics and oils, the actual experience of the paint in its wet state is of something with far less pigment load and density.

In Image 12 the only change is the removal of water, thus showing an illustration of the pigment to volume ratios after they have dried. Continuing our unpacking of how simple ratios can sometimes mask other relationships, we can see how the original PVC percentages do continue to hold true. The initial 10% pigment in the acrylic does represent 20% of the final dried film, while with casein, because we rounded numbers to make the graph easier to read, the ratio of 10/13 comes to 77% rather than the desired 72% that was reported. But still roughly correct. Also note the comparatively small percentage of binder remaining in the casein, not to mention how much thinner the resulting film is due to the extremely high percentage of water at the outset. Overall, it speaks to a film that, while being exceptionally matte and opaque, is also extremely brittle and porous and suitable only for inflexible supports. Acrylics, on the other hand, are by far the most flexible of the three systems, and have a strong enough and high enough level of binder to allow them to be reduced with as much as 1:1 with water and still produce a durable film with good adhesion, while the clarity of the acrylic binder allows for the Cobalt Blue color to retain its saturation and clarity far into the future. Oils, on the other hand, need to constantly contend with having a binder that will eventually grow yellow over time, and the 72% of oil in this color suggests why so many manufacturers will grind Cobalt and other blues in safflower or poppy oil, even though those oils produce weaker and more fragile films – a trade off one needs to be careful about.

i A brief note is also in order on the issue of the refractive index of both casein and egg yolk. While The Science of Painting (Mayer,Taft, 2000) gives this as 1.338, which is similar to sources reporting the refractive index of milk or casein dissolved in water, most commercial references list the refractive index for dry or powdered casein as between 1.54-1.67, which is what we have decided to use here. Similar discrepancy can be found with egg yolk. In “Light: Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities” (Brill, 1980) a figure of 1.353 is given, which is a common figure given in many commercial reports on egg constituents in their liquid form, while Alan Phenix, Conservation Scientist at the Getty Museum, in his article “The Composition and Chemistry of Eggs and Egg Tempera”, reports a refractive index of dried egg yolk at 1.525, which is likewise what we have chosen to report. This divide comes about as both egg yolk and casein, in their natural states, are complex emulsions where a high percentage of water plays a large role and causes the refractive index to appear to be much lower then it eventually becomes once everything has evaporated and formed a solid film. As it is this dried state that we are studying, and which ultimately shapes our perception of the paint swatches, we feel that the refractive index values given for dried egg yolk and powdered casein are more accurate.

ii Feller, Robert L. Figure 3, Percent reflectance vs. pigment volume concentration, ultramarine UB-6917 in dammar, in “The Effect of Pigment Volume Concentration on the Lightness or Darkness of Porous Paints.” Preprints of Papers Presented at the Ninth Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, 27–31 May 1981. Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC), 1981, pp. 66-74.

About Sarah Sands

View all posts by Sarah Sands -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

Hi Sarah,

This is an excellent article; such good and thoughtful research! It especially helps me to further understand and differentiate egg tempera from other mediums. I’ll be sure to share it with students and fellow tempera painters. Thanks to you and your collaborators.

Koo Schadler

Hi Koo – Thanks so much! Appreciate the positive feedback and so glad that you found the article useful. And definitely please share it with anyone that might benefit. Warm regards, Sarah

Hi Sarah,

It’s Koo again. In thinking about the article, I realize I have some questions. I’m confused what is the ultimately visual affect of PVC on chroma. On the one hand, high PVC means higher chroma. On the other hand high PVC means the irregular surface scatters light and creates a “haze of white, diffused light that appears to blend with the color of the pigment, causing it to seem lighter and often chalky or washed out.” So, does high PVC mean color is ultimately higher in chroma or washed out? Is it initially purer chroma that is subsequently diminished by scattered light? Does the local value of the color in question factor in; i.e. would the chroma of a very light value yellow be impacted differently by PVC than the more or less mid-value blues tested?

Also, why do the colors you tested appear reddish in the acrylic, wax and oil binders? I know ultramarine has a fair amount of red in it, but I thought cobalt was more neutral..? In other words, what is producing the increased red, and would other colors in those binders also show hints of red or a more pronounced appearance of whatever is that color’s overtone?

Well, as you know I tend to have questions. Thanks for being available to answer them.

Koo

Hi Koo –

Great questions and I will try to answer them as best I can. In terms of chroma and PVC, you are right that in general higher PVC should mean higher chroma up to the level of CPVC – or Critical Pigment Volume Concentration. It is when crossing that threshold that you begin to have the pigment interacting more and more with voids and the surrounding air, and thus introducing more of the haze from scattered light which will tend to lighten and desaturate the color. And yes, the value and likely even the hue of the colors will make a difference, with lighter colors (especially yellows) being far less impacted. but then, that is true when adding white to these colors as well, no? Not a dissimilar impact. And I can think of some colors that gain in chroma when white is added, or they have lower PVC, as in a glaze, such as Phthalo Blue – which in masstone, when richly pigmented, appears quite blackish but add a touch of white or use in a glaze, and the color is clearly much higher in chroma, becoming almost electric. Some of this is discussed in the article on the Subtleties of Color, which you can find here: https://justpaint.org/the-subtleties-of-color/

The question of the apparent redness of the colors in oil, wax, and acrylic might be actually easier to see if thought of as the increased blueness of these colors in high PVC systems. That you can clearly see in the color spectra that are shared in the article, where clearly there is a very dramatic jump up in the reflectance of blue wavelengths. In particular Ultramarine Blue seems quite dramatic, jumping some 40% in that area. And while lesser on the Cobalt, the jump is still quite pronounced, and it is this contrast – of the very blue masstones of the high PVC paints, that make the ones where the pigment is fully encased in a binder appear much deeper and “redder”. And if you think of it, this is not unlike the cooling effect we experience when adding white to a color, especially if its Titanium Dioxide, with its strong scattering effect. Also, keep in mind hat we all settled on a specific shade of cobalt and ultramarine blue pigments and there are certainly many, many other shades that could have been chosen. So I do think overall the Cobalt Blue that was chosen is towards the warm side of that pigment, as too the Ultra blue. If you are used to working with a different shade it could definitely make sense that you might experience these shifts less dramatically.

Hope that helps as always!

Yes, your answer is very helpful and interesting. I am always so impressed and fascinated by the complexity of color – there’s no end to learning about it. Thanks.

Koo

Great article (I really enjoy reading your articles)! Very informative. Thank you!

I have a question regarding the volume\percentage of pigment in the tube, before the paint dries. Does watercolors still have almost twice as much pigment?

The stated volume in oils, is it what Williamsburg uses or is it an average of some artist grade paints from a few manufacturers?

I am trying to understand how is it that watercolors cost about twice as much as oils.

Thanks!

Hi Johan –

Thanks for the compliment and great questions, which I try to address below.

It’s a little difficult to go from the ratios in the article to what you might find in a commercial product. The samples were all made at a very basic level of just pigment and binder, as we wanted to isolate how that ratio alone can impact the appearance of colors. However, this simplified approach does not always line up with what you would find in a manufactured product. This would be especially true with watercolors, where at minimum you would also need a humectant and a preservative, and likely other additives to improve dispersion, stability, or performance. So the actual ratios of the pigment you might find in a commercial brand will almost invariably be different from the more basic recipes we each used.

That said, if you are talking about watercolors once they are dry, or if used in cake form rather than from a tube, then yes, the amount of pigment to binder really will be much greater. This is one of the reasons why watercolors have such a beautiful, pure intensity as well as drying to a matte surface, and also why they remain so vulnerable. On the other hand, if you are trying to calculate the volume percentage of pigment in an actual tube, that is harder to generalize about. The range of percentages that Bruce Mc Evoy gives on his Handprint site feel about right and could serve as rough guide:

https://www.handprint.com/HP/WCL/pigmt1.html#pigments

(scroll down to the section on the Proportion of Pigment to Vehicle)

As for pricing, keep in mind that each medium requires a different amount of labor and work to make a stable paint that can sit on a shelf and still perform many years later. Watercolors, as you might imagine, just require a lot of attention to make well, especially with the pigments needing to be ground so finely and kept from crashing. So comparing pigment percentages alone is not quite a fair way to assess prices between different mediums. After all, if pigment load was the most important element, few things could beat a rich pastel.

Finally, the percentages given for the oil paint was taken from the actual sample that was made for the testing, which contained only pigment and oil, but overall it was fairly close to what one would expect in any high quality oil paint, with some room for variation depending on processing and the feel the manufacturer is after.

If interested in learning more about the ratio of pigments in oil, you should also take a look at the following article in Just Paint:

https://justpaint.org/volume-weight-and-pigment-to-oil-ratios/

Hope that helps!

Thank you very much! It was very helpful and completely answered my questions.

So from what I see in the different sources, oils tubes actually contain more pigment than watercolors, but due to difference in manufacturing processes, there is a big price difference also.

In regards to the fine milling in the case of WCs, isn’t it insignificant (price wise) once you start manufacturing and find the proper way to do it so you don’t lose material?

So is the price gap influenced by the fact that there are more steps in the process of manufacturing WCs? (at least it seems like there are more ingredients for the vehicle)

I’m not sure you can really state that oil paints will always have more pigment than watercolors. It depends on so many things, and of course how you choose to measure it. It is just a very different type of medium. For example, if instead of a tube of paint you started with a pan watercolor, you would clearly have a system that was more pigmented than oils – HOWEVER, to use it you have to add water, which of course dilutes the paint. So you are faced with that quandary.

Another thing to consider is that the smaller the pigment particle the more binder you need to wet out the increased surface area. Imagine you start with a 1″ cube of pigment and coat it with gum arabic. Now cut that cube in half. You will need to now coat the new surfaces that are exposed. Now cut in half again, and again, until you reach a very fine powder. With each step you will need to add more and more binder since the surface area keeps increasing, although the volume of the pigment has stayed the same. If you then charted the pigment to binder ratio, what you would see is that as the pigment gets smaller you end up with an increasingly LARGER percentage of binder to pigment.

The reason this is important is that in oils you can get away with a larger particle size because the paint is tightly bound up in a thick paste and forms a substantial film. But in watercolor, you need to have the particles quite small to stay suspended plus watercolorists prize smooth transparent washes, except in a few cases where granulation is sought after.

Hope that makes sense.

Finally as to the cost of milling, even after figuring everything out, you have to mill watercolor pigments longer, with more passes, thus more labor, and you have a much tighter acceptable range of particle size, which further adds to the process. And, while not intimately bound up in the cost of production, watercolors and oils are very different markets. One goes through a lot of oil paints in terms of volume, while a tube of watercolor might last a watercolorist years if not decades before needing another one. Plus even if it dries on the palette it can be reused – so there is never any waste. From that perspective, the more expensive watercolor tube can easily outlast the oils and, besides the initial layout, might cost an artist less in the long run.

In the end, use the medium that you enjoy and that gives you the results you want. Price should not be the driving factor and they are too different to compare easily.

Hello Sarah!

Could you help me with the CPCV calculation?

Several authors say it is possible to replace the oil absorption value (which by the way had its ASTM standard canceled without replacement) by the specific area value. Doing the dimensional analysis, the value becomes as g / m². As we are talking about concentration, shouldn’t this value be mass-by-volume?

Hi Rafael –

First, let me address your statement about the ASTM Standard being discontinued as that is not the information I have or that is listed on the ASTM Website, where both oil absorption standards (following two different methods) state they are active:

https://www.astm.org/Standards/D281.htm

https://www.astm.org/Standards/D1483.htm

If you have other information please point us to the source as obviously that is important.

As to your question, while calculating oil absorption by obtaining the calculated surface area of a pigment is doable, in truth we think it is likely not all that easy to obtain as you would need to have information on the specific pigment you are using from that specific manufacturer. The typical calculation, from what I understand, would be to obtain something called the BET-value, named after a trio of researchers that first developed the method. You can read more about it here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BET_theory

and see a mention to manufacturers turning to the use of BET values in cases where the OA values would be quite high (typically when using pigments with extremely small particle sizes):

http://www.european-coatings.com/Editorial-archive/Oil-absorption

Also see ISO 9277:

https://www.iso.org/standard/44941.html

Finally, yes, the final calculations would be reported as m2/g.

In the end, however, OA calculations using one of the older methods can serve “well enough” for a rough estimate and even then because of the variability of the particle sizes of the pigments being used – as well as the variability introduced by the formation of agglomerates – the best one usually gets is a reported range. That said, unless one has a need for something much more rigorous and precise, these ranges still allow you to get in the ballpark and from there one still ends up needing to adjust their milling or mulling to get the stiffness of paste desired.

Hope that helps!

Thanks so much Sarah!

Your answer help me so much!

It was a mistake, the Brazilian standard (ABNT NBR 5811) for oil absorption determination that was canceled, I apologize for this.

I will perform and compare some tests with the BET results to the OA results and in the future compare the values of the theorical CPVC obtained with these methods to the Mercury porosimetry.

You are very welcome! And let us know what the testing reveals.

Well amaging research. I have a question what are the solid and liquid particles are used in Matte paint and what is the percentage of that??

Hello Pranav,

Matte products are formulated to have maximum amount of pigment and matting solids while still forming a flexible film. The binder is inherently glossy, so the matteness comes from the solids. These solids can include the colored pigment itself and other inert additions like amorphous silica or calcium carbonate. There are many solids that can contribute to a matte sheen.