You would think that we would know more by now; that the questions would be answered, the arguments settled. But we don’t, and they aren’t. Even basic and fundamental issues continue to remain unaddressed by research. Will cold-pressed or alkali-refined linseed oil yellow more? Do historical and traditional processing methods lessen that? How do all of these compare to poppy and walnut and safflower? Does adding drier help or hurt? And what about the other ingredients that find their way into paint recipes? Or is a more purist approach better? What follows will not answer any of those things; certainly not in any satisfying and definitive way. But it’s a start, and we want to share our research as it unfolds. And that means many results will be provisional, even provocative, and will need time to settle into something that feels like surety. Long before and alongside our efforts, many of you conduct and share your own tests, write blogs and post in forums, take workshops and classes, all with the hope of figuring this stuff out. What we can add to the mix is the value of results drawn from standardized, controlled and long term testing, focused around similar questions and driven by a similar curiosity.

Causes of Yellowing

It is surprising how little we have been able to narrow down the causes of yellowing. This is especially true given how old the issue is. Right from the get-go, from the earliest days of oil painting, it was front and center one of the problems to solve. But over all this time, the likely suspects have only seemed to multiply. Humidity, temperature, the amount and type of light, periods of darkness, exposure to chemicals, the pigments used, the type of oil and the method of processing it, presence of impurities, the thickness of the paint, use or lack of driers, added mediums, differences in formulations, and a host of other variables, all appear to play a role. This makes any research on the yellowing of oils a daunting task, especially as the variables are not simply the physical make-up of the paints and pigments, but all the usual environmental factors that need to be controlled. And the present studies are no exception. What follows does not attempt to solve or lend support to a particular theory. Rather it simply shares our empirical findings from a multitude of tests that have been ongoing since 2010, when we first acquired Williamsburg Handmade Oils. In terms of age, the examples run from just under 9 years old up to ones that are currently 2.5 years. Collectively all of these would still be considered very young films, still in the first stages of the processes and changes that will continue for centuries.

Which Oils We Tested

We tested 14 oils in all, representing a wide range of the common ones available from different oil and paint companies, as well as more unusual options. They included 3 Alkali-Refined (ARLO) and 4 Cold-Pressed Linseed Oils (CPLO), a fifth CPLO labeled as ‘Bleached’, a water-white almost 20 year old ARLO that was kept in a sealed jar near a window, 2 additional CPLOs that were water-washed and hand-processed following historical methods, and finally a Poppy, Safflower, and Walnut oil. The oils were tested by themselves, as well as being made into a series of Titanium White paints. In that part of the testing, we followed two different approaches. In one, we created a basic, representative formula for Titanium White and simply changed the oil being used, making minor adjustments when needed to keep the thickness of the paint the same. We created a second series where the same oil and pigment were blended with different components, as a way to gauge the impact of each ingredient, moving from a simple combination of just pigment and oil all the way to a fuller and more complex formulation.

The Yellowing of Oil Alone

This area of our research held few surprises at the broadest level: poppy yellowed least, followed closely by safflower and walnut, and behind them a large grouping of linseed oils showing only the slightest variations among themselves. And perhaps just that sense of sameness was the most noteworthy and compelling feature; like most, we went into this expecting to see a clearer difference between alkali-refined, cold-pressed, and the traditionally water-washed versions. In fact, that was the initial hypothesis we wanted to document when we started these trials.

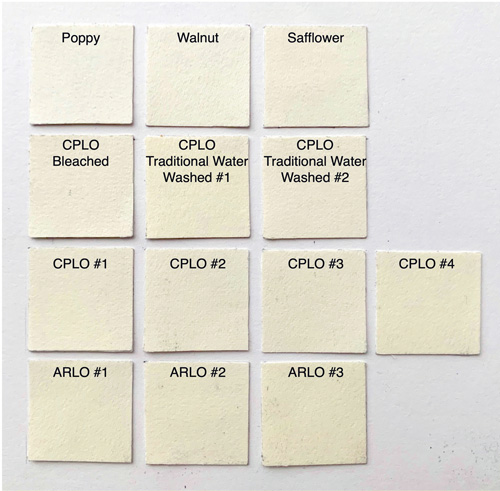

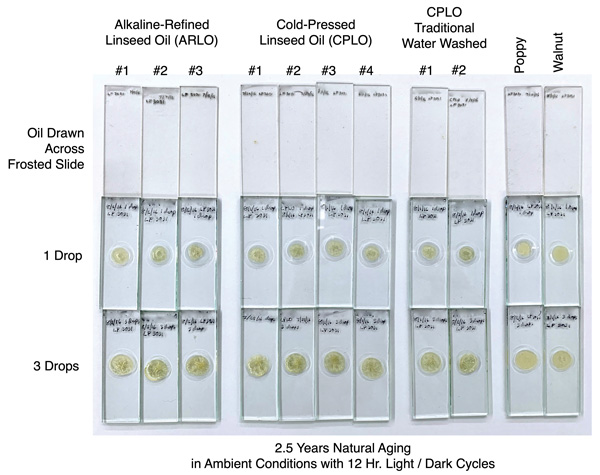

We tested oils in several ways and at various thicknesses. In one test we applied them to glass slides that were frosted, as well as ones having a small concave depression or well where we placed either one or three drops of oil. We also applied three drops to large disks of Whatman® filter paper, allowing the oil to spread outward in a uniform manner. All samples were then kept under ambient conditions, exposed to alternating cycles of 12 hrs. of darkness and full spectrum fluorescent lights. Nearly every sample was prepared in triplicate and no variance was noted in the results.

As one can see, the results on the filter paper are tightly grouped. While the poppy oil is indeed lighter, followed by walnut and safflower, all the other examples tended to be indistinguishable (Image 1). Separately, the glass slides showed similar results, although the larger volumes of oil did seem to generate slightly more variance in color, while oils like poppy and walnut displayed far less surface wrinkling, likely due to slower drying times delaying the formation of surface skin. Very thin films on frosted slides, on the other hand, appeared nearly identical across all samples and displayed such a small degree of color they appear essentially clear (Image 2).

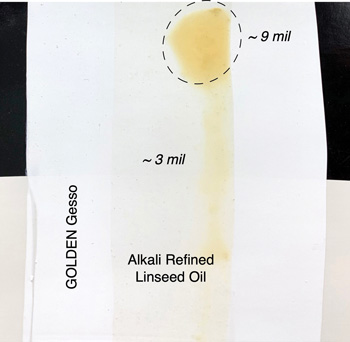

This difference between thick and thin films is something we also noticed in other testing, where 3 mil films of oil (about the thickness of a sheet of paper) were drawn down on top of acrylic gesso. In the example we show (Image 3) of an alkali-refined linseed oil, cast in 2014 and later kept pinned to a wall in an office, the very thin area has just the slightest tint of color, while the oil that spread and gathered off to the right side, culminating in a 9 mil area towards the top, took on an increasingly amber tone. Whether the drops of oil on the slides will develop along similar lines over the next 4-5 years remains to be seen.

This dichotomy between thin and thicker films of oil makes it problematic to hang too much weight on examples of yellowing where the oil has pooled and formed a solid mass, like one can sometimes find around the neck of an old tube of paint. While these can be dramatic and raise alarm, it is also true that it is never advisable to use oil in this way. Even in glazing, where mediums start to play a dominant role, the applications should always be kept as thin and lean as possible to limit any yellowing. This also holds true when working with thickened oil or alkyd-based impasto and extender mediums, where it can be tempting to create thick translucent textures that can unfortunately yellow dramatically and irreversibly over time.

From Oils to Paint

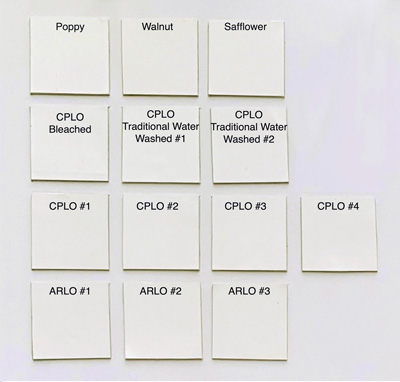

If the oils themselves felt close in appearance, things became even tighter once they were made into batches of Titanium White. After 2.5 years, what differences you can tease out are subtle at best, and the overwhelming feeling is one of similarity. In fact, the differences are so small that the inherent limitations of screens and printed pages have made capturing them reliably in a photo next to impossible (Image 4). In the end, the hoped for evidence that this or that oil causes the whites to yellow markedly more than another simply never materialized. Rather the dictum that eventually, ultimately, most oils converge toward a similar appearance would seem the better fit for what we eventually found; at least given the test conditions and time frame. Further aging might still crown a clear winner, and other factors besides the oil alone might prove to have the more lasting and decisive impact.

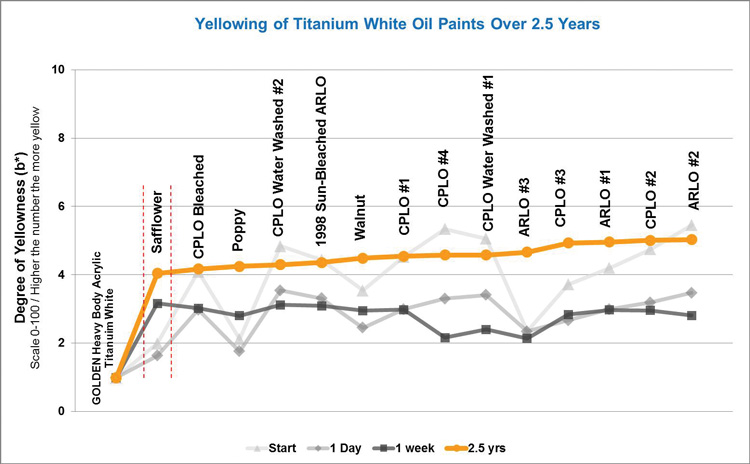

You can see this convergence taking place over time by using a spectrophotometer to measure the initial yellowness of the paints fresh from the tube and following them as they dry and age. In the graph (Figure 1) you can see that the paints have their greatest differences right at the start. After just one day most of the paints actually became whiter, and by the end of the week, when they had all dried to the touch, their differences began to flatten out. From there to their current state at 2.5 years is simply a slow drift upwards to an almost identical degree of yellowness among each of them. For a point of reference and comparison, we have also included the data from GOLDEN Acrylic Heavy Body Titanium White. The importance here is not simply to highlight the difference between the two mediums, but because the brightness inherent in white acrylic paints and gessos have set a standard that we often judge things against.

Finally, before one is tempted to read too much into the pecking order of the paints, the amount of difference between the first and last oil paint is just a single point, or Delta E (▲E) of 1, an amount considered just-perceptible for most people. Also, keep in mind that the b* scale runs from 0-100, while the graph zooms in from 0-10, allowing you to see the subtle movements that are happening. However this can also end up magnifying our sense of just how much difference you might actually notice if you saw these swatches, especially if separated by some space or in the context of different paintings.

If anything stands out as remarkable, it is perhaps the overall sameness that we noted when looking at just the oils – the different brands of alkali-refined, bleached, or cold pressed linseed, as well as traditionally cleaned and water washed ones, in the end all simply crowded close together. Does this mean that all the passions spent advocating for one or another of these variations are simply much ado about nothing? That all the claims of decreased yellowing might not matter all that much in the end? Perhaps. Or this could simply be the usual bunching-up that one sees at the start of any long distance race. We are barely out of the blocks after all, and patience is called for. Still, these results defy most expectations and stand in contrast to other panels of various whites that even we have created. That said, these are still the first large set of controlled examples that we know of, compromised of some 90 swatches all made to a similar formula and kept under the same conditions, where only the type of oil changes. We will ultimately go wherever the evidence leads, while still looking to confirm these findings in future rounds.

Impact of Formulation on Yellowing

This is an area that has remained largely unstudied in any systematic way. Research on oils in and of themselves, as well as treated by various methods, are easier to find, along with ones that blend oils with single pigments and perhaps some drier. Absent in all those are studies that take a look at the impact of all the various components that make up most modern oil paints. Our own work in this area dates back to 2010, when we acquired Williamsburg Handmade Oil Colors, and some results start to come in that are interesting to look at.

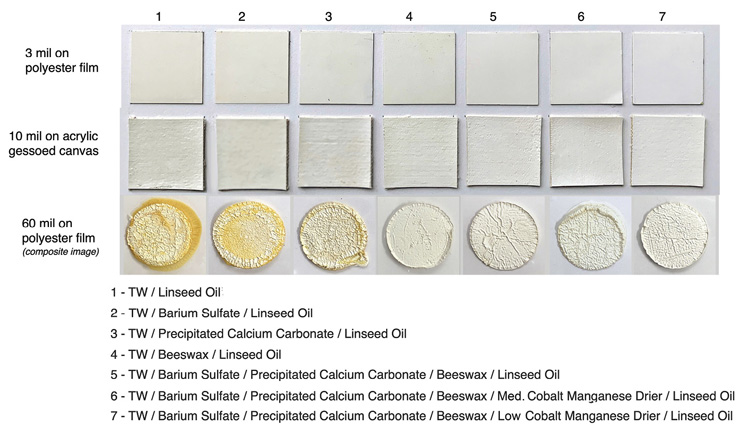

In the assembled examples (Image 5), the paint made with just Titanium White and alkali-refined linseed oil yellowed the most, belying the common belief that simple blends of pigment and oil are always the best. Perhaps even more significant is what happened when this paint was applied in a thicker, 60 mil (~1/16”) application, where you see a dramatic level of oil separation during the drying process. The next two variations, which include the addition of barium sulfate or precipitated calcium carbonate, become increasingly less yellow while also showing a corresponding drop in oil exuding to the surface or out the sides. This sets up a strong correlation between yellowing, at least with Titanium White, and the paint’s ability to fully bind and hold onto the oil and prevent it from seeping out. This would also explain why the paints become significantly whiter, especially in the thick application, once beeswax was added in as a stabilizer, or why the addition of drier on top of that would help even further. The beneficial effects of drier in this regard is noteworthy as far too often it is claimed that their use leads to more yellowing, not less. This is the opposite of everything we have observed. However, these tests do not include the full range of available drier combinations, their use in distinctly different paint formulas, under different environmental conditions, or at levels that would be considered excessive.

While the pressing-out of oil is dramatically captured in the 60 mil disks, it is worth speculating that a similar but much smaller-scale process could be happening in the thinner swatches as well – namely that oil is rising to the surface at a microscopic level, and forming a thin, yellowed film around the topmost layer of pigment. This phenomenon around the formation of a skin of medium on top of the paint has been noted by current researchers of modern oil paints, although the exact cause has not been established (Izzo, F.C., et al, 2014; Burnstock, A. et al, 2014; Cooper, A. et al, 2014). We also know that this type of phenomenon is one of the main reasons that Zinc Oxide was used so frequently in conjunction with titanium dioxide. Essentially Zinc Oxide’s rapid ability to form metallic soaps and create a laminar, crystalline structure, appear to help hold the oil in place, although at the cost of creating a brittle paint film, especially at higher levels. The combination of beeswax and drier used in these tests might be helping along similar lines, but without the downsides with zinc.

Dark Yellowing

Dark yellowing is a well-known phenomenon where oil-based paints stored in the dark will yellow significantly, although the yellowing is thought to be fully reversible by exposing the paints to light (Levinson,H., 1965; Townsend, J.2011). This is an area we have written about before (Sands, S., 2014, 2017) but never comparing the rate and extent of recovery based on simple pigment/oil mixtures alongside a more fully formulated paint. Having a selection of swatches kept in dark storage for around 6 years, and examples of the same formulas kept in ambient, indoor light for 3 months and another set for 2.5 years, has led to some interesting results (Image 6).

Differences in yellowing could be found in all three stages. Of the swatches kept in the dark, the one made with cold-pressed linseed did the worst, followed closely by alkali-refined, then safflower and the others. The paint made with just pigment and stand oil did the best in this category, although it should be noted the paint itself was unpleasant to work with because the oil was so viscous. The fully formulated paint did far better than the same pigment mixed with just ARLO or CPLO, and in the end nearly equaled the paints made with safflower or that included zinc in the mix. It is also critical to note just how long it took these paints to recover from long-term dark storage when exposed to just typical indoor light levels. After 3 months the recovery was still only partial when compared to similar examples in the same room for 2.5 years. Thus the time needed to fully reverse the effect of dark yellowing can take far longer than many people might realize. Needing this type of long recovery period has also been noted in more recent conservation research (Townsend, D., et al, 2011) where the required period for pieces kept in prolonged dark storage was thought to extend to multiple years in gallery lit conditions.

The Making of the White Paints Used in the Tests

For testing of the 14 different whites, each of the paints was made using a basic formula of oil, titanium dioxide, synthetic precipitated calcium carbonate, barium sulfate, beeswax and a low level of cobalt-manganese drier. These were then cast directly onto polyester film that was either uncoated or had a layer of acrylic gesso applied as a ground. We used polyester because it is non-reactive and stable, while the addition of acrylic gesso simulates some of the absorbency one gets when painting on a typically primed canvas. The samples were then stored under ambient conditions with light coming from color corrected fluorescent bulbs on a 12 hr. light/dark cycle, or else in an office with similar fluorescent lighting supplemented with indirect window light. They have not undergone any prolonged dark storage.

Things Not Tested

In any test, what is left out can be as important as what is included. We did not control for humidity or temperature, two environmental factors commonly linked to increased yellowing. No mediums were included. The driers were limited to either a low or medium level of a single cobalt-manganese combo, and a host of other potential modifiers and additives were left out, such as hydrogenated castor wax, magnesium carbonate, and aluminum stearate. The range of substrates and grounds were also very limited, and we mainly cast the paints onto polyester film that was either coated with GOLDEN Acrylic Gesso or left plain, although one set of examples were applied to acrylic gessoed canvas. In terms of pigment, we tested only one type of rutile titanium dioxide, supplemented by zinc oxide in two examples, but did not test basic lead carbonate, lithopone, or zinc oxide by itself. Finally, we did not include other brands of paint for comparison since we had no way of knowing their exact ingredients, and therefore no way to know what might be responsible for any results in either direction.

Conclusion

At the moment, none of this testing will definitively resolve which oil or formula of Titanium White will yellow the least. But at least it starts to give us a controlled set of paints kept under controlled conditions that can form one basis of the discussion. More rounds of testing using fresh drawdowns of yet more variations, are in the works and as those results come in, and these original swatches continue to age, we will certainly publish and share those findings. This is work and research that will literally go on for decades, long past the lives of most of us in the Lab. The hope is that in the future, when all those questions about oils and yellowing continue to be asked, that the answers will have a firmer footing.

References

Burnstock, A, van den Berg, K.J.,“Twentieth Century Oil Paint. The Interface Between Science and Conservation and the Challenges for Modern Oil Paint Research”, In: van den Berg K. et al. (eds) Issues in Contemporary Oil Paint. 2014, Springer, Pages 1-20

Cooper, A.,Burnstock, A., van den Berg, K.J., Ormsby, B. “Water Sensitive Oil Paints in the Twentieth Century: A Study of the Distribution of Water-Soluble Degradation Products in Modern Oil Paint Films”, In: van den Berg K. et al. (eds) Issues in Contemporary Oil Paint. 2014, Springer, Pages 294-310

Izzo F.C., van den Berg K.J., van Keulen H., Ferriani B., Zendri E. “Modern Oil Paints – Formulations, Organic Additives and Degradation: Some Case Studies” In: van den Berg K. et al. (eds) Issues in Contemporary Oil Paint. 2014, Springer, Pages 75-104

Levison, Henry, “Yellowing and Bleaching of Paint Films”, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Spring, 1985), pp.69-76

Sands, Sarah, “What is Dark Yellowing?”, Just Paint, Golden Artist Colors, August, 2017, www.justpaint.org/what-is-dark-yellowing/

Sands, Sarah, “Williamsburg’s New Safflower Colors”, Just Paint, Golden Artist Colors, Issue 30, February, 2014, www.justpaint.org/williamsburgs-new-safflower-colors/

Townsend, J., Carlyle, L., Cho, J.H., Campos, M.F., “The yellowing/bleaching behaviour of oil paint: further investigations into significant colour change in response to dark storage followed by light exposure”, ICOM-CC, 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon, 19-23 September 2011. p. 1-10

About Sarah Sands

View all posts by Sarah Sands -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

Excellent, excellent article and research Sarah!

Thanks Richard – as always I truly value your appreciation for the work and research we do.

Fascinating – thanks, Sarah!

Thanks Jean! Definitely some curious results that ran counter to some of our own expectations. Will be interesting to see where this ends up at the 5 and 10-year mark.

Why were the test done only with Titanium? What about the yellowing of Lead White?

Hi Avery. We did not purposively ignore Lead White as much as simply needing to start somewhere and Titanium White is unarguably the most broadly used white for paints and grounds. Plus it has some unique issues, like its tendency to push oil to the surface. Our hope is to include lead white in future rounds, as well as lithopone (PW 5), and to explore more fully the impact of functional solids as well as stabilizers like aluminum stearate that are used broadly by artist paint manufacturers, although we have chosen to use small amounts of beeswax ourselves. So a lot to look forward to!

Dear Sarah,

Thanks for this valuable work.

I recently had some issues with yellowing with cold pressed linseed oil which i’d purchased in a raw state and then cleaned myself and allowed to lighten in the sun for 12 months for use with hand made paint and mediums; It mainly seems to be an issue with yellowing in the dark – but it is much more pronounced then when in the past I made mediums with stand oil and damar resin.

To avoid this problem i’ve switched to hand refining cold pressed walnut oil – this has has made a cleaner and brighter paint but the handling qualities of paint/medium made with this oil is very different than oil paint/mediums made with linseed oil. The walnut oil paint has far less resin like qualities compared with the hand refined linseed which is something I miss.

Kind regards,

Darren

Hi Darren – Thanks for the comment and sharing your experience. In some future iteration, we hope to include more walnut oil, and especially a water-washed one, just as another variation to look at. It is, along with linseed, one of those classic oils stretching back to the Renaissance, but is often talked about has having a thinner, slippery-like feel which some love, but others will miss – as you seem to do – the more bodied feel of linseed oil. In any case, hand-refining oils is always a great way to learn about them and gain some insight into the past. And if we can ever help further, just ask!

Dear Sarah,

This is a very thorough examination of the darkening of oils. I am very appreciative of Golden for providing artists with these results to think about. Interesting (figure 5) how bees wax (sample 4) reduces surface oil to inhibit yellowing, and so does low cobalt drier (sample 7) but not high cobalt drier (sample 6). I was under the misunderstanding bees wax increases yellowing. This is an area palette knife painters could consider, as knife work has had the reputation to increase yellowing by drawing oil to the surface. What were the concentrations of cobalt drier and bees wax used? I am interested to see where this study heads to in about 10 years time, especially with stand oil and bees wax. Thank you once again.

Kind Regards

Sam

Hi Sam –

Thanks for the compliments about the thoroughness of our testing and the sharing of the results. Feedback like yours means a lot to us. Also, know that the spirit of open-ended inquiry and a desire to make as much information available as we can are cornerstones of our culture here. In terms of your questions, you are correct that beeswax has that reputation but we think it is tied more to the fact that, at higher percentages, it increases transparency enough that the inherent yellowing of the oil is not masked. Given the opacity of titanium white, the very small percentage of beeswax in the mix (less than 3%), and its role as simply helping bind the oil and stabilize the paint, it has a net positive effect overall. And at substantially higher levels, say 10-20% or more, you will start to produce much softer paint films that are more susceptible to solvents, slower drying, and, yes, more yellowing! The notion that palette knife painting by itself causes oil to come to the surface is intriguing and I will need to look into our testing around thicker applications to see if we find a similar issue, or at least to add that variable to the mix. As for the cobalt drier levels, the differences in the thinner films was very slight and it’s hard to capture those type of subtle temperature shifts in an image, so I think the difference you see is a touch larger than you would sense in real life. But it is true that in the thick disks one did see a clearer difference. My guess here – and it is something that would need to be proved in further rounds – is that the higher level of cobalt drier causes the top of the thicker application to skin over faster and that this skin in turns acts as a diffusion barrier to oxygen and delays the crosslinking lower down, thus allowing more unbound free oil to be mobile for longer. But just a theory. Clearly, too, you can see that the cobalt drier at both levels increases surface wrinkling in thicker applications for similar reasons – the quick skinning-over caused principally by cobalt (a surface drier) happens when the paint is at its original full volume, then as it loses volume from off-gassing and shrinks, you get those tell-tale puckered and wrinkled surfaces seen in thick oil paint applications. As for the exact percentages of the drier, that is something we do need to keep proprietary as it takes a long time through trial and error to start to locate those ranges. We hope you understand. But certainly, in general, you should find roughly similar results if you push levels towards the lower and upper range recommended by whatever cobalt/manganese drier you happen to be using. Just keep in mind those percentages would still not be the same as ours since we are working with extremely concentrated pastes that are not available to painters directly. For reasons of safety and ease of control, the driers you find in art stores are provided in a more diluted liquid to be added dropwise.

Hope that helps!

Excellent information, thanks Sarah & Golden. What % volume addition of barium sulfate or calcium carbonate to TW would you have used? Wondering how to best balance the risk of yellowing caused by increasing transparency against TW alone, while acknowledging it’s not definitive yet

Your standard tube formulations don’t usually contain beeswax or other stabilisers? (does Williamsburg TW including unbleached titanium normally contain beeswax)?

Hi Bob –

Thanks for the questions. Because much of the testing we shared was based on and working towards our own optimizations, we are not able to share the percentages as that is proprietary. It becomes part of the art of paintmaking and things gained through multiple trials tested over the years. And keep in mind that beyond just percentages, the type of calcium carbonate or barium sulfate would also impact the results. So it’s a bit complex. The main point we wanted to show is that these inert additives have an impact on the results which can often be positive and that frequently there is a synergy among different components that is greater than any one of them alone. Not completely unlike the fact that Titanium-Zinc is whiter than either Titanium or Zinc separately. As for our standard tube formualtions, we do use small amounts of beeswax not only in Titanium White and Unbleached Titanium but in general across the line at extremely minute amounts (generally in the 1-2% range) representing the bare minimum needed to prevent separation over longterm storage and, as the testing also showed, there are times when it also contributes to other qualities, such as less yellowing. Hope that helps!

Thanks very much Sarah, helpful as always. I also wonder, does Williamsburg add a small amount of bodied linseed oil to pigments like raw umber to help prevent sinking in? Seems like a good idea as sinking in can happen even unexpectedly on a well prepared support. I’d prefer that to me adding extra oil to the painting

Hello Bob,

Thank you for the comment. Sarah is on sabbatical, so I’m happy to answer your question. We do not add bodied oil to any of our Williamsburg paints. Although it is an interesting idea, it may be a bit of a slippery slope trying to predict what characteristics to accentuate through formulation. In the end, we prefer to keep our ingredients as simple as possible and leave the rest to the creativity and technique of the artist.

We have also seen sinking in and matting of oil surfaces even on well prepared and on non-absorbent test surfaces. The thickness of the stroke or application, the pigment and/or the binding oil can all have an impact on the surface sheen of the dry oil paint. You have likely seen this, but just in case, here is a link to Sarah’s article on oiling out and dead spots: https://justpaint.org/oiling-out-of-dead-colors-in-oil-paintings/

Take care,

Greg Watson

How much time does it take for an oil painting to start getting yellow ??

In our testing with straight oil and whites made with different types of oil, the samples tend to settle into a degree of yellowing withing a year or two. whether or not you will be able to see yellowing in a painting depends on the dominant colors in the work and how well they can hide the yellowing of the oil. Some colors are more vulnerable than others to yellowing – whites and blues in particular.

Best Regards,

Greg Watson

Thank you Sarah, and great to read this.

I wondered if you had any advice regarding how to deal with a yellowed area of a painting (created with 50% walnut oil and 50% Williamsburg titanium white)?

I have a painting that I had to put in dark storage,for about a month, just a few weeks after it was painted, and it yellowed noticeably. Do you know whether this is reversible and if not, whether a thicker (more pigment heavy- straight out of tube) white paint, could be used to paint over the yellowed area (without having the same thing happen again?)

I wondered if there might have been an adverse reaction between the alkali processed linseed oil titanium white and the walnut oil medium?

Thanks for your help!

best,

Daniele

Hello Daniele,

We would suggest putting the painting in direct sunlight and then checking periodically to see if the yellowing wanes with exposure. It is likely to take more than a couple hours of sun, though.

Warm Regards,

Cathy

Thanks so much for making your research available to artists, it’s so valuable. Could you outline the two different water washing methods used? Also curious which “historical texts” these washing methods come from?

Hi Christopher –

Thanks for the comment and we are so glad that you found this helpful. In terms of the water washing, the two oils were from outside sources and not prepared by us. One is from a commercial company that specializes in water-washed oils based on ‘historical texts’. Unfortunately, they do not share what those texts are or the exact process that they follow. Obviously there is a range of hand-washing methods that can all claim to be historical, but the current field of handwashing is also small enough and well-researched enough that everyone is generally aware of the same information. While certainly possible that an exotic or rarely used method is being employed, I have tended to believe that it is some variation of the water-washing methods described in de Mayerne’s “Lost Secrets of Flemish Painting” and/or the variation on it laid out in “Methods and Materials” by Charles Eastlake. The second hand-washed sample was supplied to us by an independent scholar and specialist using the general sand and water method developed by Tad Spurgeon, who is well regarded in this area and also draws from the above texts, as well as his own research. On a personal note, I have repeatedly followed Tad’s sand and water process myself at different times with results that at least appeared similar, although I think even Tad would acknowledge that there is always some variation involved. In the long run, the inclusion of just two samples does not make for a definitive conclusion about water-washed oils but we hope they represent at least what is typically being used by many painters interested in these things. Hopefully one day we can drill down further and generate a range of oils ourselves so we can more fully speak to the exact methods and processes used.

Hope that helps.

Thanks Sarah, that’s all very helpful, I am familiar with these texts and with Tad’s extensive work on the subject so I’ll look back at them. I am always looking for practical and proven ways to improve the durability and look of paint so it’s great to see your team approach these topics so rigorously, despite doing many of my own tests over the years it’s hard to trust any of the results without repeated confirmation from others, and despite my best efforts I doubt I can control as many variables as your lab.

Related to yellowing or darkening with age, I’ve never been able to find any information on the quantity of manganese in umber pigments and how it compares to the quantity in the drier additives. Is there concern for the manganese in umber pigments to darken or yellow on their own or in mixtures with white? I’ve always considered the iron oxides to be the gold standard of stability, expecting that the increase in transparency with aging might cancel out any mild darkening in darker umber passages. Is there concern for significant changes/yellowing with age among siennas and umbers due to aluminum soaps, manganese, etc? Thanks so much.

Hi Chris –

There is a good article analyzing manganese-containing pigments used in art, which includes chemical analyses and Mn % of various commercial oil paints: Study of the chemical composition and the mechanical behaviour of 20th century commercial artists’ oil paints containing manganese-based pigments As you see, in Table 3, the Mn % in Umbers ranged from 3-11%. I would not get too locked in to which brand had what – both of these are naturally mined and the percentages of all the components will invariably be, well, variable! But it at least gives a ballpark. Trying to compare this to the percentages in commercial driers is complicated. Commercial Mn driers will have concentration ranges from 6-10%, but will be added into the paint at a very, very small fraction well below 1% by weight. Then how available the Mn is in the pigment, versus the metallic salts, and the complex range of other metals that the umbers bring along as well, and I am not sure a direct comparison is practical without a lot of analysis. In terms of yellowing, however, I have not seen evidence that the Mn in umbers would contribute to it. And of course, as we shared in these tests, despite the often voiced concern about driers causing yellowing in whites, at least in terms of Titanium White we found the opposite – that the judicial use of driers actually aided in preventing yellowing. Finally, we have never seen reports raising concerns about the yellowing of umbers or oxides. By far the greatest concerns with these natural earths has to do with hydrolysis, where interaction with humidity causes a weakening of the paint film. You can read more about that in this excellent article by Marion Mecklenburg: The Influence of Pigments and Ion Migration on the Durability of Drying Oil and Alkyd Paints

Hope that helps!

Hi, reading.this again, thanks again for.the information. Assuming the drawdowns are done with a palette knife, this causes more oil to rise? Or are tests swatches applied with a brush?

Hi Bob –

The drawdowns are done with a drawdown bar, which you can think of as just a very controlled ‘palette knife’ like application done at a very specific, uniform thickness. So definitely not brushed on, which is harder to standardize from person to person, and more difficult for a spectrometer to read due to the surface texture. I am curious, though, about your comment of a palette knife causing more oil to rise to the surface. It is not something I had heard of before, so looked for some reference to the phenomenon but came up empty. Is this something you have seen or is there a source you can point us to?

I am wondering what version of linseed oil yellows least…Regular Linseed Oil, Cold Pressed Linseed Oil, Refined Linseed Oil or Sun Thickened Linseed Oil. Would you please answer this for me? Thanks so much!

Hi Mary – Thanks for the question. In our testing and experience, Cold-Pressed Linseed Oils, while they can sometimes do quite well, are just very variable as a product and can differ not just from manufacturer to manufacturer, but even batch to batch. Sun-Thickened Linseed will yellow the most among these options, and really its main attraction and use are that it dries quickly, levels, and is viscous. If wanting something with a similar feel, but don’t mind that it dries slowly, then Stand Oil is one of the least yellowing options among linseed oils. Not sure what you are referring to by Regular Linseed Oil since nearly all of the linseed oils you will find for artists’ use, which is not labeled specifically as Cold-Pressed, is Alkali Refined and is what most people would think of as being the regular and most common choice. And really that is also the one we would recommend as being the most consistent and reliable. Hope that helps!

Dear Sarah,

you seemed curious about palette knife causing oil to rise to the surface. From my experience, the oil is somehow drawn to the top when a palette knife is used, compared to brush work. I wonder if it is a capillary action or the pigment sinking. It seems to happen over a few days/weeks, just something I notice with my work as the paintings appear glossier with time. I am not sure if Vincent Van Gogh encountered the same problem, as he asked Theo to wash down his paintings after they had dried to remove the excess oil. I have also read about palette knife use and rising oil somewhere but cannot recall where.

Hi Sam –

It is true that titanium white by itself does not bind the oil very strongly within the paint film, leading to oil being able to exude out, although one can improve its performance through the use of other materials in a fuller formulation. We even show that in the article – see image 5, especially the dramatic examples on the thicker 60 ml disks on the bottom row. But as to why a palette knife would influence or cause it remains a mystery. As for Vincent Van Gough, he would not be painting with titanium dioxide, which did not come into general use until the 1920s. Anyway, if you do find anything that speaks to the phenomenon let me know, and in the meantime, we can add this to our list of curious things to test.

Thanks for the article. I’ve used linseed oil paint and love it. However, the yellowing property is unwanted. Do we know how visible light affects the paint to reverse the aging? Does the UV spectrum have anything to the non-yellowing?

Also how was beeswax added to the samples and in what form?

Hi Scott,

Yes, most types of light seem to reverse dark yellowing. The brighter the light the faster the color will loose its yellowish cast and come back to its pre-darkened state. But, dark yellowing is different than the long term yellowing of a color. Long term yellowing cannot be reversed with light. Most colors do settle into a color after a couple years, then seems to remain stable.

In these test samples the beeswax was added during production. It was melted into a portion of the oil that was used to make the paint. It was not just added as a cold wax addition or as a medium.

We hope this helps.

Greg

Just a follow-up to this. I’ve used the same whitish linseed oil paint in the same room that doesn’t get much light. The paint on the woodwork has yellowed and darkened. The painted metal bathtub color hasn’t changed a bit. I wonder why? Is there some reaction to the wood that causes yellowing that isn’t present in metal surfaces?

Hello Scott,

Is the tub painted with oil paint or is it the enamel typical for a cast iron tubs and sinks? As the enamel on the tub should not change over time. If you have used the same paint on the bathtub as you have on the woodwork, then perhaps the wood itself might have darkened over time and is altering the brightness of the white color. Some woods can produce stains that travel through the paint layer. Also, if the wood work is in the shadow and the tub area gets a little more light, it may be enough to hold off any dark yellowing that can occur in the oil paint layers. This is interesting, as different surfaces even when painted with the same color, can appear different depending on the light that illuminates that surface.

Feel free to email [email protected] with any follow up questions.

Thanks,

Greg

Hi Sarah,

Thank you very much for your excellent article. I recently had issues with yellowing, and two conservators I consulted referred me to your article.

I have a question: do you think acrylic paint Titanium Dioxide has the same yellowing issues as oil paint?

With many thanks,

Maryam

Hi Maryam –

So glad that they referred you to the article! The yellowing of Titanium White in oils is truly due to the nature of drying oils used as a binder, while Titanium White in acrylics will retain its bright whiteness.

Hope that helps but please don’t hesitate to ask if you have other questions.

Wow! Thank you for your quick reply Sarah. That really cracks the code for me. How fascinating. We are lucky as painters today to have access to shared knowledge and an array of materials.

A deep bow to you and all the helpers!

Maryam

Marfa, TX

And a deep bow to you in return. If we can help any further just ask!

Excellent research! It was published 4 years ago – have there been any updates?

Hi Peter,

Thanks for your comment. Sarah reports on the 5 year update in this article: https://justpaint.org/yellowing-of-oils-update-and-new-testing-at-the-5-year-mark/

We will keep checking in over the years and decades to see how it changes over the long term. Stay tuned!

Greg

This is an absolutely fantastic resource. Thanks so much for taking the time to document and report on this– so useful!