The Material Specialists here at Golden Artist Colors are often requested by artists to diagnose the reasoning for problems occurring in their paintings based solely upon their words used to guide us. One of the most common emails or calls require the understanding of whether the artist is discussing a crack versus a craze in the paint film, and exactly what shape the crack or craze is. Both of these conditions are caused by a similar mechanism of reducing stress in the paint layer. Often these stresses are built up during the drying process yet some cracks may only appear with some other mechanical and / or environmental stress in the future. Understanding the causes of these fractures in the paint film will both allow for corrective action or point the artist in a way to take advantage of what might be to others, a paint defect.

What the Heck is a “Craze”?

A craze is typically considered a surface defect, developing most often in acrylic paints or mediums that when applied, begin to form a skin while the material underneath is still fluid and wet. The very flexible acrylic film can usually stretch quite easily as the edges of the skin begin to dry, requiring the center of the film to continue to stretch as water evaporates and the film shrinks. In some cases, the center areas of the drying film can no longer take the stress of shrinking and a tear in the upper part of the film occurs. This then leads to a phenomenon where water and other volatiles are more able to be released from this area of the tear. It’s sort of like lifting the cover off a boiling pot to one side; all of the evaporative pressure is now targeted at this area of the film. Sometimes this tear can reach all the way down to the paint layers below, but even more often the surface film repairs itself, yet left with the scar of the original tear and still noticeable on the surface. Although a craze is a physical surface depression, it does not pose any long-term stability issues to the painting. The film formation process has not been compromised.

At times the crazing phenomena can occur in very thin films. More often than not, this sort of crazed surface is the result of the lack of a coating being able to wet out the layer below. So as the stresses caused by the evaporation of water continue, areas where the cohesive force of the acrylic film is greater than it’s attraction to the substrate or paint layer below, you begin to see these same crevices in the film. In extreme circumstances this crazing can actually leave breaks in the film.

Products which do not relax or flow after being applied to a surface do not have the same issue of crazing when applied. For example, Soft Gel, Heavy Body Acrylics, and Molding Paste are artist materials that are highly unlikely to craze even when applied generously to a canvas. The shrinking product’s structure remains stable during drying. One can overcome this by adding a generous amount of water to these products. The additional water simply increases the amount of shrinking that will occur in the drying process and therefore increase the stresses in the film.

When is the Defect Defined as a “Crack”?

Cracks are also the material’s way to relieve stress. They can be identified by their crisp breaks. The sharp-edged individual pieces are defined as “platelets”. Some cracks occur when a hard, rigid paint layer is flexed further than it is physically capable of bending. These cracks run deeply throughout the entire painting. When decades-old oil paintings on linen are carelessly removed from their stretchers and rolled up tightly they are probably going to crack severely. Even acrylic paints, primers and gel mediums can crack. Acrylics are thermoplastic and when they are in cold climates they become increasingly stiffer. When they are rolled or unrolled in the wrong temperature they can crack, even if they exhibit no issues in warmer room temperatures.

Another reason paint layers may crack is because the underlying materials are swelling up, pushing against the less elastic layer. At some point the stiffer paint has to give, and it creates a cracked surface. Exterior grade housepaints are formulated with a high degree of elasticity in order to reduce the cracking that occurs when the underlying wood swells from moisture.

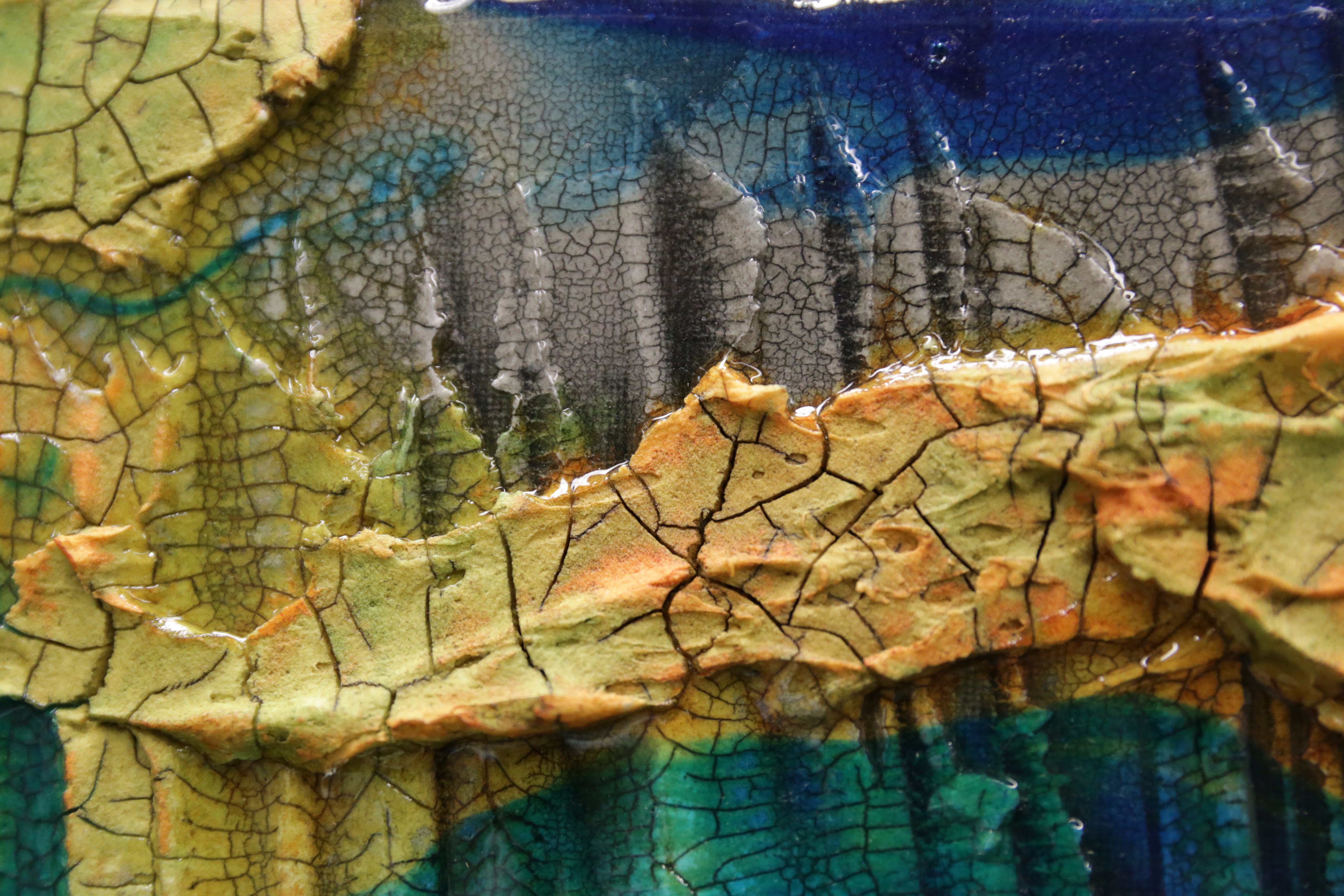

Some artist materials crack due to their formulation. When a product is overloaded with “solids” such as marble dust, it becomes more than the binder system can handle. The shrinking film tries to stay intact, but must yield at some point, and again, cracks are a result. This cracking resulting from a material being under-bound is observed in nature when a riverbed or lakebed dries up. The mud cracks, forming deep fissures. This phenomenon is the reason our Crackle Paste works. It relies on being under-bound just enough to develop a cracked (also known as crackle) layer. Of course, we have to be very careful as to modify the solids to binder level just enough to cause the pattern to develop, and still be stable enough for use within artwork. Proper surface preparation and sealing the surface after the cracks are done developing are paramount to long term stability.

In the Ceramics Industry crazes and crackles are both defects and decorative. They often are the result of the glaze recipe or the speed of the cooling off cycle after firing the pottery. The pattern develops as a means to reduce stress or tension within the coating. Craquelure is used to define a large or complete area of fine line patterns.

Unintentional cracking or crazing often happen during the painting process when the artist least expects it. Some are the result of applying a paint, gel or medium a bit too generously, and others happen because external factors such as temperature, humidity and air flow are not taken into account. Even if an artist has used a product successfully for years, defects can occur. When troubleshooting, consider the impact of the immediate environment and changes in the weather. What worked perfect in the summer may not work at all during the winter months.

Crazes can be minimized through careful planning and control of the product application and studio environment. While it’s near impossible to completely eliminate crazes from developing, one can greatly reduce their occurrence by:

• Working in a room temperature environment with little air movement, especially during the initial drying phase.

• Applying products thinly and avoiding thick puddles or dammed sections.

• Working on a flat, level surface.

• Avoiding movement of the work until it has cured, ideally leaving it alone for 3 or more days.

• Allowing underlying paints and primers to fully cure.

• Sealing the absorbency of the surface before applying a poured layer.

• Suspending a lightweight board such as Gatorfoam® just above the surface of the freshly applied medium to create a terrarium-like environment that slows the drying time down.

Take note of when crazes or cracks develop in your own work. Look at all of the factors present and narrow down the most likely factors that resulted in the defects and conduct tests to see if you can mitigate their development. The product you applied may be the wrong product for your desired application. If you are not able to figure out what’s going on, contact us so we can help you identify the problem.

Hi, My acrylic dirty pours are crazing. I want to add GAC 800 to my paint mixes.

How much GAC 800 do I add? Do I add it to every colour or only 1 or 2 colours?

Thanks

Hello Cynthia,

Thank you for your questions. The GAC 800 needs to be the primary product in all of the paint mixtures. I often mix around 10 parts GAC 800 to 1 part paint. This can be adjusted if you want more opacity or transparency, but more paint begins to result in more crazing, and can be color dependant. A 4:1 GAC 800 to paint ratio seems to be a good threshold for the amount of paint to add, but if you tilt the painting while wet and stretch the paint out it will dry faster and be a thinner paint layer, both of which help reduce the chance of craze development. You might also want to “tent” the fresh pour using cardboard or plastic to slow the drying time down. For small thin paintings you can simply use a clean pizza box.

– Mike

I have a Sam Timm painting with crazing (only with your help have I been able to put a name to it) It makes the picture look rustic but I worry about resale value. Does an artist ever use a technique that created that rustic appearance . Can an artist create a crazing look on purpose? Thank You

Hello, Karen.

Thank you for your questions and comments!

Sam Timm is – as you know – known for his realistic scenes of country landscapes and wildlife scenes. It might be possible that he created a work with intentional crazing, but it would be atypical for him to do this. I think that it is more likely that the canvas you have is a printed reproduction, and that it might be what’s called a “Giclee” print which uses a high-quality ink-jet printer.

The canvas is prepared with an ink-receptive coating that relies on being somewhat water-sensitive to allow the inks to absorb into it and then dry. If this water-sensitive coating gets printed and not properly sealed, or if moisture comes in from the backside of the canvas as with humid environments, the coating can swell up and develop crazing and cracking. I think this might be more likely than the artist doing this intentionally.

If the artwork surface doesn’t have any signs at all of brush stroke texture, it’s most likely a print, and Timm’s work has been greatly reproduced for many years.

You might be able to get an artist to carefully touch up the work, but it may need to be sealed with some of our GOLDEN Archival Varnish, which is a spray varnish to help with UV protection and protect artwork (and prints) from moisture.

I hope this helps out!

– Mike Townsend

Dear Cynthia,

This was very helpful. I am very new to this, I usd to paint but after a couple strokes I can no longer express myself as I used to….but still have a lot of paints so pouring on a small scale seems doable to me…..but as I look at videos and Facebook, it appears cracking is a bad thing, yet some of my favorite pieces are ones with cracking….often used as examples of what not to do……is that just personal preference? Or is there something I am not understanding. I like texture or the look of texture but that seems to be something to avoid. Thanks for any insight!

carolann

cracking can be good and bad Carolann. If cracking is the result of poor film adhesion it could result in paint cupping and falling off. If it’s shallow crazes, then the crazes are not going to be long term stability issues. Here’s an article on these differences: https://justpaint.org/defining-the-difference-between-a-crack-and-a-craze/

– Mike

Hi Michael, if you get a large crack on an acrylic pour can it be filled in and with what Golden product? I used a mixture of GAC 800 and Liquitex Pouring Medium and a small amount of Floetrol. My painting looks great in all areas but one. Thanks, Karron

Hello Karron.

Filling in cracks/crazes can be tricky to not make it stand out even more. I believe the best approach is to use the exact same mixture and skim it over like one does spackling. Remember that acrylics shrink, so several passes (allowing drying in between layers) should eventually result in a more uniform surface.

– Mike

Thank you so much! Great article! Sharing to all artists I know.

Thank you, Bethany!

Your comments are much appreciated.

– Mike Townsend

Hi Mike,

also temperature shocks might cause crazing:

two years ago on a very hot summer day I applied a layer of self leveling gel. Knowing the studio would get even warmer when the sun turns around the corner I tried to slow the drying process (and thus to prevent crazing) by putting this small painting into the most shadowy corner of the studio, not being aware that the difference in temperatures in an old building can be enormous. I could immediately watch the fast crazing process. Fortunately spread almost evenly over the surface I could encorporate the crazes later.

Hi Wally.

Thank you for your insight about factors that contribute towards crazing. Ideally acrylics are allowed to dry in “room temperature” which is within the 60-80 degrees Fahrenheit range.

– Mike Townsend

Mike, I’m just getting into painting with acrylics. I caught where you suggested a 60-80 degree when allowing paintings to dry. What do you suggest the humidity should be ?

Hi Denise.

Thanks for your question.

Temperature while acrylics are curing is important because it can impact the coalescing of the acrylic polymers. Too cold, or too hot, can alter the process and create weaker paint films.

While painting, higher humidity helps provide longer working time. For fast drying, lower humidity accelerates this. So, for most acrylic artists they prefer having more painting time and when they are done painting and need the paint to dry quickly it is very helpful to have low humidity and some air movement. But humidity doesn’t greatly impact the curing of the paint as temperature does. As with “room temperature” maintaining a comfortable humidity level is the studio is preferred. Anything lower than 70% RH will help the paint cure. Higher than 70% will help slow the drying time down. When doing pours, high humidity can greatly reduce the chance of crazes developing.

– Mike Townsend

Hi Mike,

Thanks for posting this article. Very informative!

I’ve recently been getting into acrylic pours. My last couple have crazed. I did allow some outside air to hit the paintings after they were poured, but also I am wondering if old flow acrylic could have caused that. It was near the end of the bottle and it did not have a very good seal on the lid. Could this have played a factor? Could too much silicone also cause crazing?

Thanks in advance!

B

Hello Kitbry!

Thank you for your kind words and questions.

When you blend a cocktail of products together, it’s very hard to know if one of the additives are the culprit in developing crazes. Mixing each color well does help, as does keeping the overall mixtures similar to one other helps as well. Perhaps if you create a larger mix of the base blend you can test it with a specific amount of paint and see how it fares.

The most effect measure I have seen has been to “tent” or cover over the pour to create a humid micro climate. This slows the drying time down to allow the entire paint film to dry more evenly. For smaller pours a clean pizza box works great! Try to leave the paintings be for as long as you can without moving them. Ideally wait 3 days before picking up or moving the painting.

Hope this helps reduce the crazing!

– Mike Townsend

Hi Mike

I’m new to this too , I wanted to paint on large canva , but I wanted to make texture to all of it , I found on another site some one who advice for that to use stucco with pva 3:1 ratio … and I did so .,but as soon as it dried alot of little cracks appeared . Now I’m upset , I don’t want to get rid of it and I don’t want to spend more time and effort to find that pieces of it started to fall down ..is there a substance to paint which can fill the cracks befor acrylic painting ….

Thank you very much

Hello Nedaa.

Thanks for contacting us with your questions. We would not suggest to use stucco meant for walls and PVA glue especially on canvas, as this mix would be much too stiff and brittle, and mud cracking seems very likely because of this. The better option would be to use products meant for creating texture on canvas, such as the GOLDEN Molding Pastes and other similar products. These products are intended to be used thickly on panel and canvas, and are developed to be flexible enough to not mud crack during drying or crack when bent. In regard to your other question about filling, the problem is that even if you are able to fill the cracks of the stucco/PVA layer, you are very likely to see future cracking and delamination. PVA tends to have water sensitivity, so if you can’t flex and peel the paste off of the canvas. Remove as much as you can before applying an artist grade paste product. – Mike Townsend

Hi Mike

I found on another site that I can use stucco and pva to give texture to my canva in 3:1 ratio …and I did so ,but I found plenty of little cracks in it what can I make to seal these cracks together before painting with acrylic colors please .

Hello Nedaa.

Sorry for the delay in response but we do appreciate your comments. Creating texture onto canvas using stucco and PVA is a bit of a gamble because you would need to add enough PVA to avoid “mud-cracking” during drying, or cracks from movement after it dries. An acrylic medium such as Fluid Matte Medium might be enough to saturate the spackle and help secure the texture, but you may have also simply created too weak and brittle of layer that even that could still allow for the texture to flake off from the canvas.

– Mike Townsend

Hi Micheal,

Appreciate the time and effort in maintaining the website and active flow of comments.

As for my question. Reading on the matter here and thus knowing that GAC 800 should be the main part of a mix with acrylics [10-1] I do use it but at a level of 10% ……. in a PVAc/water mix. Any thoughts on that?

Experiences of drying, flexibility, and overall look and feel are pretty good. But then again my experience [4 months] is nill as it comes to art. Surfing on the acrylic pouring wave which brings a lot of fun, but also a lot to study. If with a 10% participation in the mix GAC 800 loses its functionality is there any other product or solution to keep a pour mix a good quality for a modest price? And maybe you guys could figure out a good mix or setup for the acrylic pouring community which is affordable and still gives a good enough quality result.

Again, thanks for the continued effort with testing and informing whoever wants to come over and read some reports.

– Regards, Jan.

Hello Jan, and thanks for your questions.

At a 10% level the use of GAC 800 isn’t really overly different than adding any other acrylic medium in regards to film integrity. You might find that using Gloss Medium or GAC 500, etc would work just as well. The GAC 800 with just paint is the best chance for non crazing, and when blended with more water, again, most acrylics would perform similar similarly. My greater concern would be the heavy use of PVA glue. Be sure that type you are working with is tested to be resistant to yellowing and cracking over time.

That said, we are always working on improving products and certainly appreciate a more affordable acrylic medium designed for pouring would be very welcome in the painting community! You have our ear.

– Mike Townsend

Hello Michael. Very nice information provided. I have a chromolithograph from Louis Prang c1874 that appears to have crazing in one area. A darker green tree area. Do you think this is possible on a chromo with so many layers of ink applied?

Hello James.

Thank you for your question. I would assume that the cracking you are seeing doesn’t pertain to the crazing that develops during the acrylic process. It may just be from the ink’s thickness and age. I would suggest contacting a print conservator at AIC (‘Find a Conservator’ section) and ask them about this. They may be able to help identify the cause and potential repair of the print.

I have a Sam Timm painting with crazing. Not sure if it is a print or an original. Can crazing develop on a print. It makes the painting look rustic. Does an artist ever deliberately try to create that appearance? Does it devalue the picture or enhance it? Thanks for your info otherwise I would not have known what was wrong with it.

I recently decided to creat textured art with acrylic filler and white glue on canvas for sale but it keeps cracking.

I’m I using the wrong products or what should I do to stop it from cracking?

Also, how do I fix the cracked textured art?

Hello Lorinda.

Thank you for contacting us with your question. Cracks can often speak to poor film formation. You might be adding too much filler, or using the mixture too thickly. Ideally, acrylic mediums are better suited as your binder. GAC 100 or Gloss Medium would be better – Mike Townsend

HI! I recently came upon your page after I had my first horror filled realization that my InProgress oil painting has started to crack in certain areas. I believe its because I used to much linseed oil on the section that has begun to crack.

My question is: Is it possible to continue painting and cover up these cracks or should I restart the entire painting all over again? I’ve never had cracking happen to me before so Its new to me.

Hello, Kayla.

This kind of cracking in oils is very different than what you get in acrylic films. There are many reasons why an oil paint film can develop cracks. Here’s an article about oil paints used over acrylics and the type of cracking we noticed during testing. Once you review this article, contact us at [email protected] and please provide details such as the surface, how it was prepared and with what, the brands and colors of oil paints used, and if you use mediums and their percentages. Any other situational issues that may have occurred while you painted this work are very helpful as well. Such as very cold temperatures in the studio, etc. – Mike