Please Note: What follows is an update to long-term testing that we first wrote about two and a half years ago. The original article provides important background and context for understanding the current results, and can be found here: On the Yellowing of Oils

Yellowing after 5 years

It’s the first rounding of the curve that provides one of the most exciting moments in a race, with its allure of easy wins and illusions of leads that can just as easily evaporate on the straight of way. And so it has been with the yellowing of oils. At least at the five-year mark. The distinct differences that we saw in the very early stages have been replaced with an increasing sameness as if there was some inexorable pull towards a common destination. Which is incredibly odd, if you think about it. Aren’t these different oils supposed to give different results? So many books and articles and artists have attested to such. So what gives? Why are we not seeing what we had expected to see? We will share some thoughts about potential reasons in the sections ahead. But first, let’s get our bearings and take a look at where things stood and where they are today.

When we last looked in 2019 this strong confluence was already starting to take shape. The various oils, after two and a half years of aging, had all but erased the initial differences from the first few weeks. But like any snapshot, it’s hard to intuit if you have caught things in their frozen final state or just at a particular moment before going their separate ways, like a group photo taken at graduation.

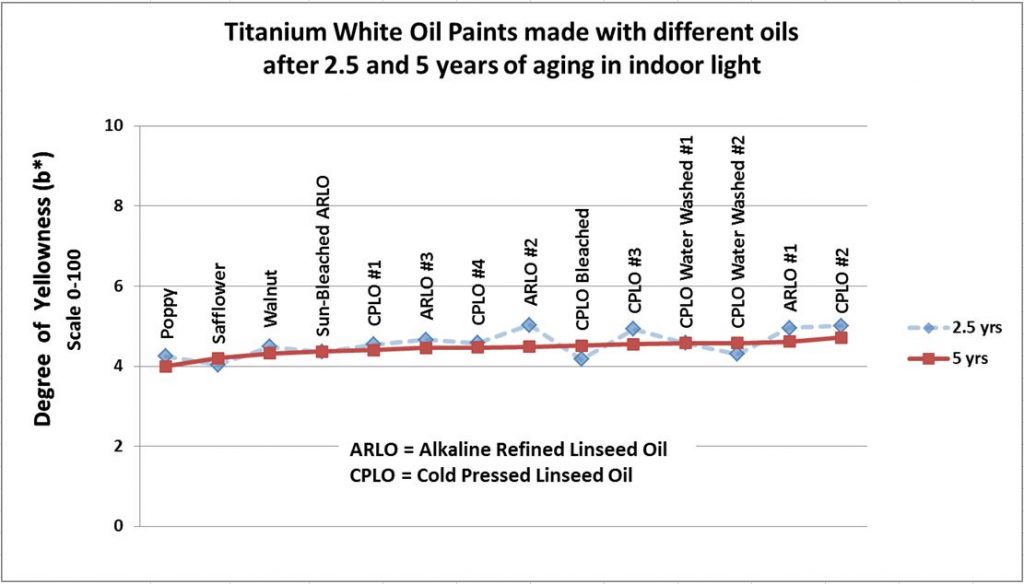

Below we show the degree of yellowing for all the different oils as they were at the beginning of 2019 when they were 2.5 years old, and then now, at 5 years (Graph 1). And as you can see, there is literally no significant difference between the two.

A word on how we measure yellowing. One of the things a spectrophotometer tells us is how blue (-b*) or yellow (b*) a color is, using a color space called CIELab. You can see a model of that color space here. So we simply track or compare a color’s b* value over time and as it yellows more, that value will increase.

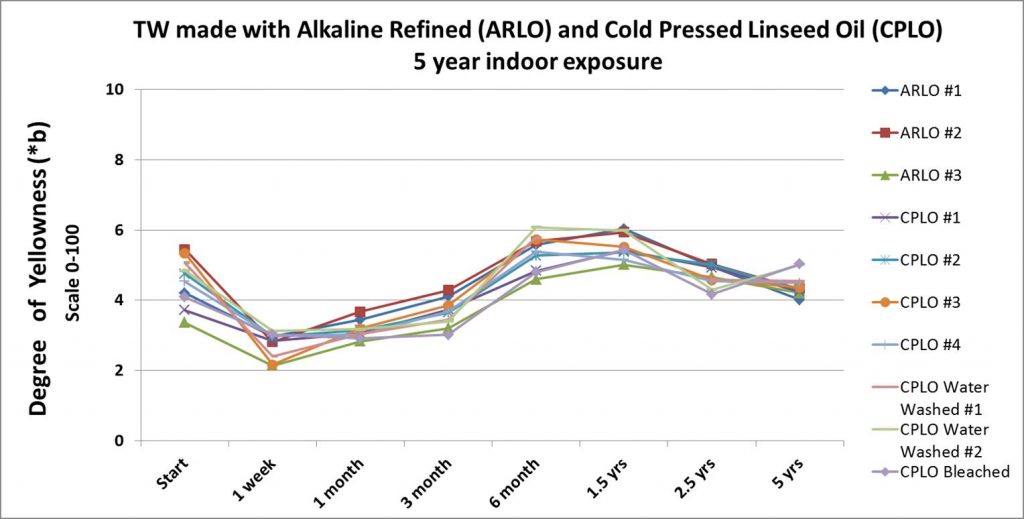

And just to have a more complete view of the five-year period, here is a graph for all the Alkaline Refined Linseed Oils (ARLO) and the cold-pressed linseed oils (CPLO) where you can see how close they are tracking each other (Graph 2):

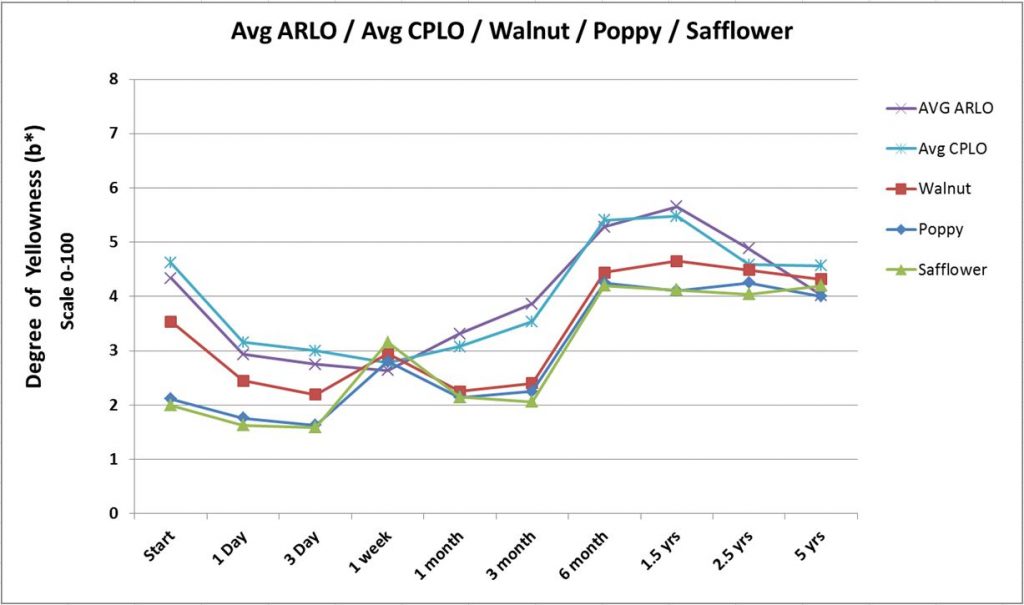

Then, just to make things less crowded and clearer, we graphed the average readings of the alkaline refined linseed oils (ARLO) and the cold-pressed linseed oils (CPLO) alongside the three singular oils of walnut, poppy, and sunflower (Graph 3). While there is a little more differentiation, the sense of similar groupings moving in lockstep with each other to a similar endpoint is hard to ignore.

It is certainly possible that the differences we were hoping for will not show up until much further out at the 10 or 20-year mark; that we are actually witnessing a race of turtles rather than hares. A more interesting possibility is that whatever unique properties the oils might have, are being overridden by sharing the same basic recipe. That perhaps formulation is more the driver of yellowing in various whites using linseed oil, rather than the processing of the oil itself? Certainly last time we showed how a single alkaline refined linseed oil could perform very differently depending on the recipe being used, so the reverse – that different oils could perform similarly in the same formulation – seems at least conceivable and something to look into.

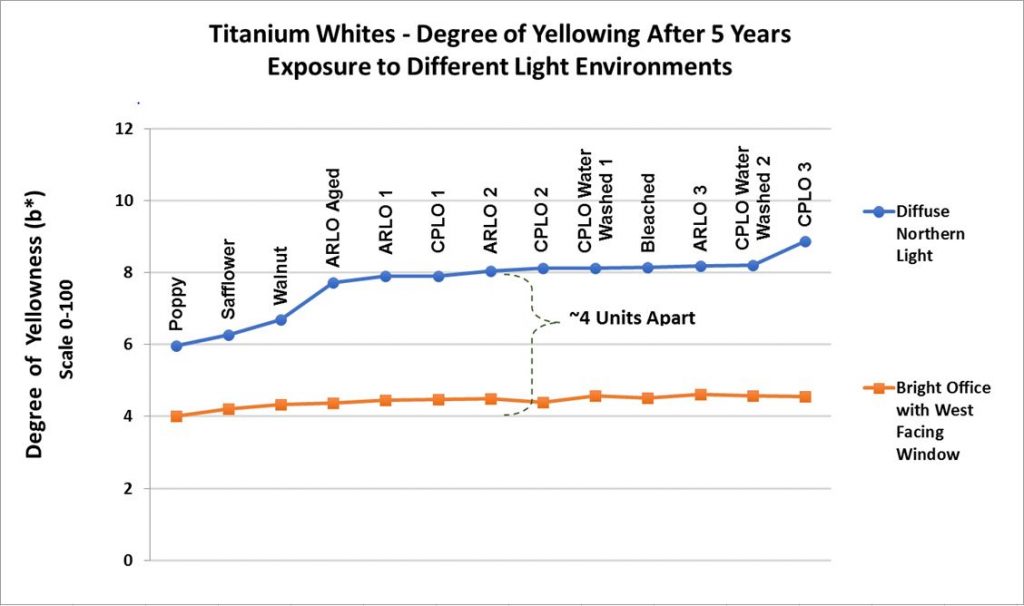

We also thought that perhaps the light was evening things out, essentially bleaching away the differences in yellowing that would normally develop. After all, these samples were being kept less than 10 feet away from west-facing windows, as well as overhead office lighting that over time had moved from fluorescent to LED, and from being off at night and on weekends to being on 24/7. Luckily we had an identical set kept over the last five years in a studio setting, with diffuse northern window light and overhead LED lighting used moderately during the year. Below you can see the results from the spectrophotometer readings (Graph 4):

Clearly, differences emerged that were being masked and evened out by the lighting conditions. For example, poppy, safflower, and walnut are now more distinctly separated from the rest. However, all the various linseed-based paints, except for one cold-pressed example at the end, exist on the same type of flat, straight and nearly unwavering line as before. Just that now the line runs parallel some four points higher, which means they were clearly more yellowed but by an almost identical amount. So the ability of the formulation to at least narrow the range of differences still seems plausible. To give you a better sense of the differences and similarities between these two groups, we share some examples below (Image 1).

Impact of Thickness

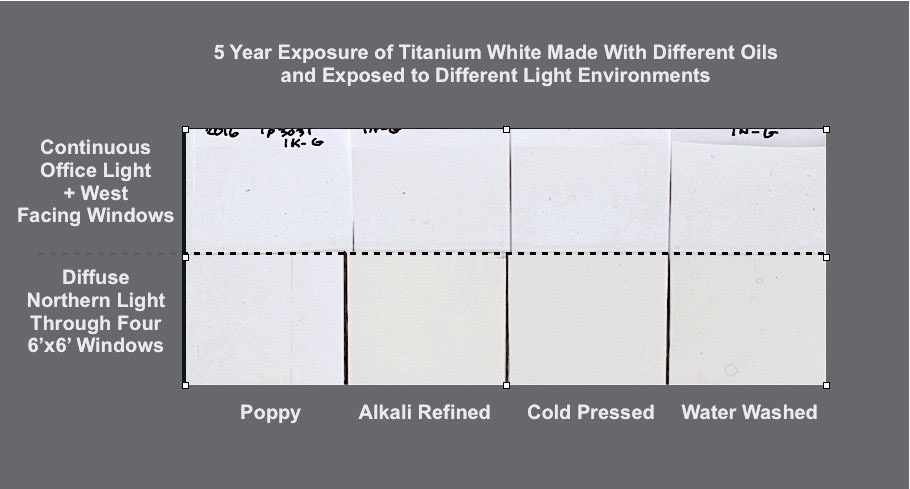

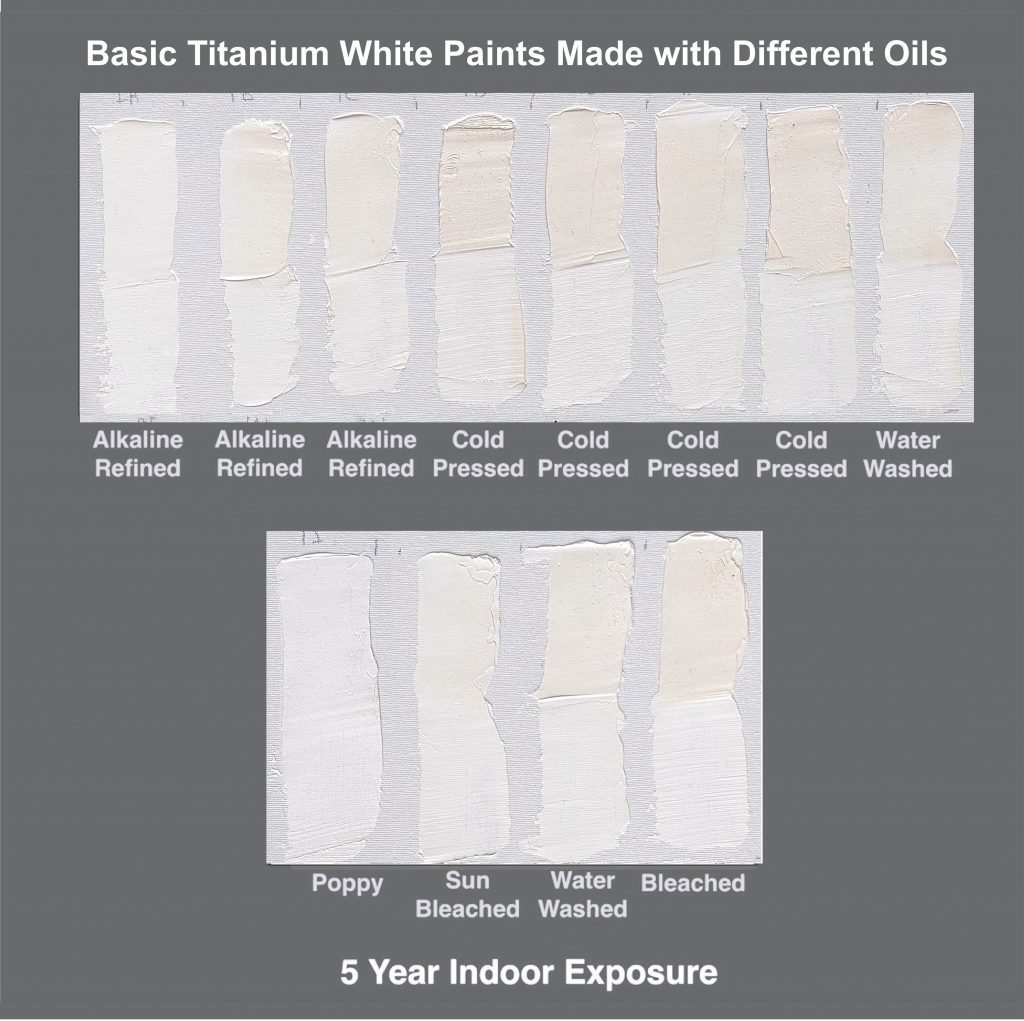

One of the things we pointed to last time was that thickness of an application can make a difference, and certainly our drawdowns, at 6 mil (approximately the thickness of two sheets of copy paper), would be considered on the thinner end. So we were interested to compare the above samples with some test panels where the paint was applied slightly thicker at one end, using a palette knife, followed by a thinner area below. See the following image (Image 2) for a sense of that range:

Below are the samples we did, covering all the oils minus the walnut and safflower (Image 3):

Certainly in the thicker parts additional differences among the oils start to be teased out – the first alkaline refined sample literally rivals the poppy, followed by the next two to its right and the sun-bleached below, while the bleached and one of the cold pressed swatches are now clearly darker and more yellowed than the rest. In the thinner sections, most of these differences are minimized. A range can definitely be seen, but it’s tighter in. One possible explanation is that titanium has a hard time holding onto oil, especially in thicker applications when the longer drying time allows more oil to gravitate to the top. Once there, any yellowing would be less masked by the pigment and other components, revealing the differences between the oils more easily. And of course in the thinner sections, because the film dries more quickly, the opposite would be true.

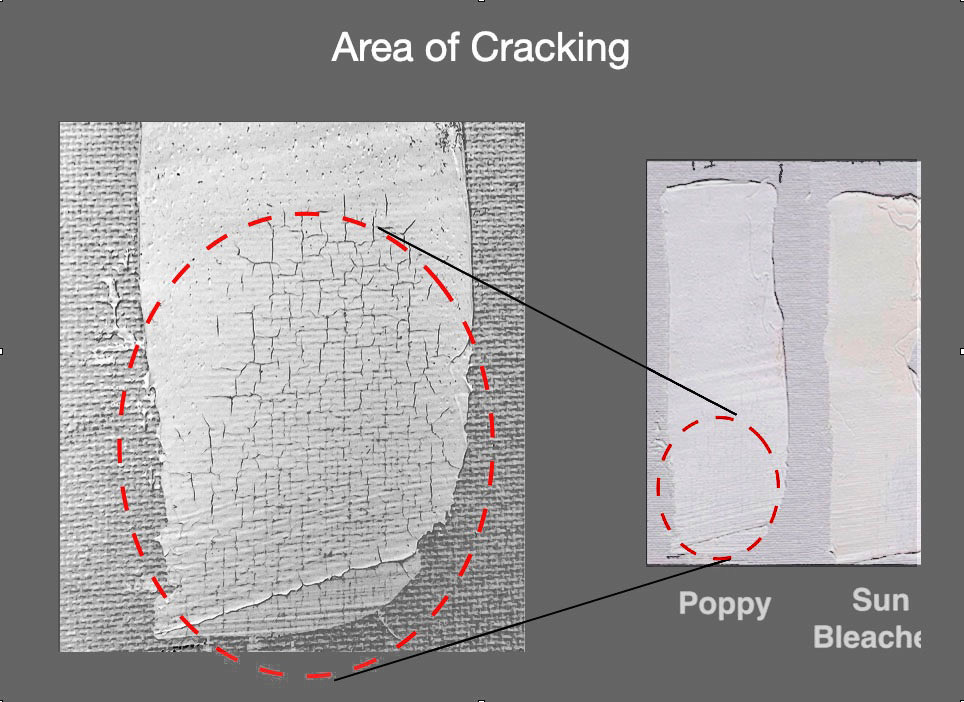

Before we leave these samples, there is one more thing to point out. While the paint made with poppy oil has done remarkably well in terms of yellowing, and we saw no surface defects in the earlier drawdowns, significant cracking has developed and can be seen here in the thinner area (Image 4):

It could be that the canvas texture made the paint film more vulnerable to any shrinkage as it aged, that being so thin, it couldn’t continue to bridge the peaks and valleys of the weave as it contracted. If nothing else, it certainly points to a more fragile film than seen in the other paints at this point.

Conclusion

Those are the specific updates we have at this point, including some of the curiosities we encountered and the questions that invariably lead to more questions. We still want to have a deeper understanding of how the formulation of a paint impacts yellowing, versus the intrinsic properties of the oil or how it was processed. And there are things to understand about the role of lighting, environmental conditions, and the thickness or type of application. So there’s a ways to go yet. Our hope is to keep updating these results as the paints slowly make their way to the 10-year mark and beyond, while also sharing new tests meant to answer new questions.

About Sarah Sands

View all posts by Sarah Sands -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

This is brilliant! Thank you so much for doing this work and write up Sarah 🙂

Hi Richard – You are so very welcome!

Interesting article! Thank you for this research. Do you suspect any relationship between the poppy oil cracking and its protectiveness against yellowing? Something about how it dries or mixes with the pigment, for example? I was thinking, “Well, the poppy oil looks great!” until that last photo, and I wondered if the the same thing that made it less prone to yellowing is what made it more prone to cracking.

Hi Lori –

A great question and kudos on making the connection since, in a very broad sense, the answer is yes! In fact, just as you wondered, all the less yellowing oils, including even our own Safflower ones, form more brittle and less durable films. They also lose more mass and shrink more as they dry. If interested in how and why, I would recommend our article on the Safflower colors which does reference Poppy as well. In this specific case, we are not precisely sure which of all the variables caused the cracking so we are going to have to look into it further. For now we just wanted to point it out as it surprised us as well.

As for the lighting, it is usually the UV (ultra-violet) exposure that yellows plastics, so I would think it would be the same for paints. Sunlight, fluorescent, and LED all emit UV light. Within the UV spectrum, there are different wavelengths, normally designated A, B, and C. Generally, we expect UVA to affect color perception the most, while UVC tends to accelerate skin damage faster. It would be good to accurately measure the amount of UV actually landing on the paint sample surfaces. (Note that the angle of the lighting also makes a difference, so be sure to keep the light meter’s sensor parallel to the surface, not angled toward the light source.)

Hi Pamela –

My immediate response was just how much I love the questions and observations that people like you share, and the dialogs that ensue from that. You are absolutely right that this type of data would be important to know – and unfortunately, it is something we failed to gather at the time but certainly can go back and get some readings to estimate exposure and have a fuller record. That said, the mechanism for yellowing in plastics versus the type of yellowing being studied with oil paints is different. To just point to some examples, oil paints yellow more in the dark, in a process called Dark Yellowing, and the general degree of yellowing of a drying oil is correlated with the degree of unsaturation of the fatty acids rather than UV exposure, which if anything tends to help reverse any yellowing that accumulated in dark storage. The first article covering the yellowing of oils touches on some of this. While certainly UV has to ultimately play some role in the aging and breakdown of oil paints, just like other materials, and thus possibly contributing to yellowing in the long term, I just am not sure it is doing so within the time scale and conditions that oil paints are typically studied under. But will admit I have not looked deeply into the literature – so I also want to keep an open mind. And if you have any references concerning oils, UV, and yellowing, I would be very very interested!

Hi Sarah

I find interesting the finding about cracking of poppy oil based white. I have thought for some time about asking, or rather suggesting a test you could make; it would be interesting if you did a test focused on strenght of various oils. Just as you tested various color containg zinc white (i.e. zinc buff, naples yellow reddish, king’s blue here: https://justpaint.org/zinc-oxide-reviewing-the-research/) you could test various pigments (natural inorganic, synthetic organic and inorganic) in various oils (linseed, walnut, poppy, safflower) to see whether they crack. I asked about this at MITRA forums in context of one article at naturalpigments.com: https://www.artcons.udel.edu/mitra/forums/question?QID=874

Ivan

Hi Ivan – While we haven’t done a systematic test as you are suggesting, we have looked at different oils (Safflower and Stand) used with Zinc plus a few other pigments, as well as comparing the oils to each other. But nothing extensive or very broad. In terms of Zinc, preliminary data has shown that Stand Oil might be very promising but we need to see if that holds up long term. And of course, making a paint purely with Stand Oil, much less working with it, is not really ideal or practical. However, if the stand oil was used as an additive or medium, it could perhaps help. We will need to see as we continue looking.

In general, I would expect oils with fewer unsaturated bonds to do better in terms of the specific type of embrittlement caused by zinc. But over and above that, the different oils already dry with differing amounts of strength and durability caused by the loss of volatile components and the corresponding shrinkage that takes place. Both of those, in turn, are linked to the creation of a more porous film. For some sense of that, see Chart 3 in our past article introducing Williamsburg’s New Safflower Colors. At this point, my own speculation is that the craquelure we saw in the poppy-based film was due to the shrinkage and contraction of the paint more than actual embrittlement. But further testing will be needed, and keep in mind, this was made from pigment and oil only, and a more fully formulated paint would likely perform differently. For now, we simply wanted to draw attention to what we saw.

Hi Sarah

I wonder how is it with potential yellowing/darkening of pure oils? If a liqiud oil, e.g. Williamsburg Alkali refined linseed oil, is stored in a glass bottle (whether clear ar amber toned) in shadow or dark place, can it darken too?

Hello Ivan,

Thank you for your great question. The effect of dark storage on wet, bottled linseed oil has not been studied by us, nor elsewhere, to my knowledge. We have not observed dark yellowing with any of our Williamsburg wet products. In general, the effect of day and UV light is that it lightens/bleaches linseed oil, and the effect of polymerizing linseed oil with driers or by heating it, yellows it.

Spectacular update, these are like Christmas when they come out!

Is there any research showing that the yellowing can be reversed with sun/UV exposure? I’ve heard of stories of folks putting oil oil paintings in the window for a few weeks to brighten the whites again. Is this true?

Hello Walker,

In general the yellowing of oil paintings caused by aging is permanent, while dark yellowing can be reversed through UV-exposure. The latter is probably what these people were experiencing when taking their paintings from either storage of a place on an interior wall to the bright daylight next to a window. Here is an article on dark yellowing: https://justpaint.org/what-is-dark-yellowing/.

Best,

Mirjam

Hi–If I’m looking at this image correctly, you seem to have used 3 different samples of alkali-refined linseed oil: https://justpaint.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/TW-with-Different-Oils-Extract_lighter-1024×1021.jpg

There is a significant difference in the yellowing. The first one is almost perfectly white–comparable to the poppy oil. The other 2 have yellowed noticeably. Could you please specify the brands/sources of the different oils? I would definitely want to be using the least yellowed one!

Hello Paul,

We understand your curiosity regarding which oil if from which brand or manufacturer, however, we purposely don’t enclose competitor brand names, in order to maintain good relations within the industry. We hope and trust you’ll understand.

Best,

Mirjam

Sorry that I missed your response until now, but I have to reply that this makes all your hard work and data almost worthless to me as a consumer! You are showing three samples of the same kind of oil, and one is clearly better than the others. It is very interesting to see how much variation there can be from one brand to another, but what am I supposed to do with this information? Also, in this image (https://justpaint.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Same-Swatches-in-Diff-Light.jpg) you are showing one sample of refined linseed oil which has darkened in lower light. But which one is it? Is it the really white one from the other image, or one of the more yellow ones? Since the three brands clearly behave quite differently, this should be specified.

Hello Paul,

Sorry for your disappointment. The focus of this study is to determine how much change in yellowing occurs as oil ages, and the differences between oils in general. Keep in mind, that the examples shown are not whites made by other manufacturers, but a controlled formula made in our custom lab using the different oils as the only variable. Because the other ingredients in an oil paint formula can have dramatic impact on yellowing, disclosing who bottled the oil would not necessarily mean their white would provide the same results we are presenting. Likewise with the example from the image you shared, the effect there was to show that the same sample stored in different lighting conditions can have drastically different results. It is likely that all the alkali refined linseed oil paint samples had a similar amount of change between the brightly lit office samples and the north lit studio samples – around 4 delta units of change. This was to show that dark yellowing is a very real phenomenon with oil paint that should be considered when storing or before exhibiting paintings. All oils darken in low light, with linseed oils yellowing more than poppy, safflower or walnut oils in our study.

Here is an article about dark yellowing for more information on that topic: https://justpaint.org/what-is-dark-yellowing/

We hope this helps to clarify our intention for this article. Best wishes in the studio!

Greg

Any possibility of testing stand oil, as a comparison to the other oils.

Cheers Sam

Hi Sam,

We didn’t include stand oil paint in this testing results simply because it is not an oil any manufacturers use as the primary binding material. As mentioned in the original article, we have made paints with stand oil in the past which are very long, stringy and hard to use. But, the samples we have around the office are looking rather white with age. Perhaps we can work those results into the next update!

Thanks and take care,

Greg