Dark yellowing is the reversible, temporary yellowing that dried oil paint undergoes when stored in the dark or subdued lighting. While noted in many historical writings, most painters remain unaware of it and become surprised or concerned when they discover it happening to their own works. Which makes sense. With no other context to go by, it could easily feel like something has gone terribly wrong, or is aging prematurely before one’s eyes. What follows is an attempt to put some of this in context; to show multiple examples so you know what to expect, mention some of the research, and suggest things you can do if you discover this happening in your work or primed canvases.

Despite its long history, surprising little is known about the actual mechanism behind dark yellowing. We know it happens when oil paintings are kept in dimly lit or dark conditions, and that it can be easily reversed when exposed to light. However, the precise chemical process remains a mystery, at most attributed to the accumulation of some unknown ‘chromophore’ – a generic term for any molecule that happens to produce color. The phenomenon is most pronounced in linseed-based paints, although all drying oils will dark-yellow to some degree. And finally, at least among white paints, the actual pigments can matter, with a clear distinction between Lead, Titanium, Zinc, or a Titanium-Zinc blend.

Testing

In terms of scientific research, only a handful of past studies have focused on this topic, which we list in our references at the end. For the most part, despite some differences in approach and sample sets, the studies draw a similar picture: dried oil paint can seemingly undergo cycles of dark yellowing followed by bleaching indefinitely, with variations attributed to the length of dark storage, the age of the film, and the level and duration of light exposure. Joyce Townsend, in the most recent study (2011), suggested that works kept in dark storage or dim light for very long periods would most likely take a number of years of exposure to ‘typical gallery’ lighting to recover.

Our own tests have focused on standard white paints and oil grounds, brushed out or drawn down on different surfaces, without additions of mediums, and either placed completely in dark storage, or else kept in a room with lights on for approximately 12 hours a day, with one section always covered with an opaque strip of black plastic. The light in our application area would be the equivalent of a well-lit workplace or studio with 700 lux of illumination. At the end, all the pieces were exposed to a total of 8 hours of direct bright summer sun to get a sense of the maximum whiteness that could be recovered. Obviously we would strongly caution against exposing artwork to similar levels of direct sunlight, especially if there are any concerns about the lightfastness of your materials.

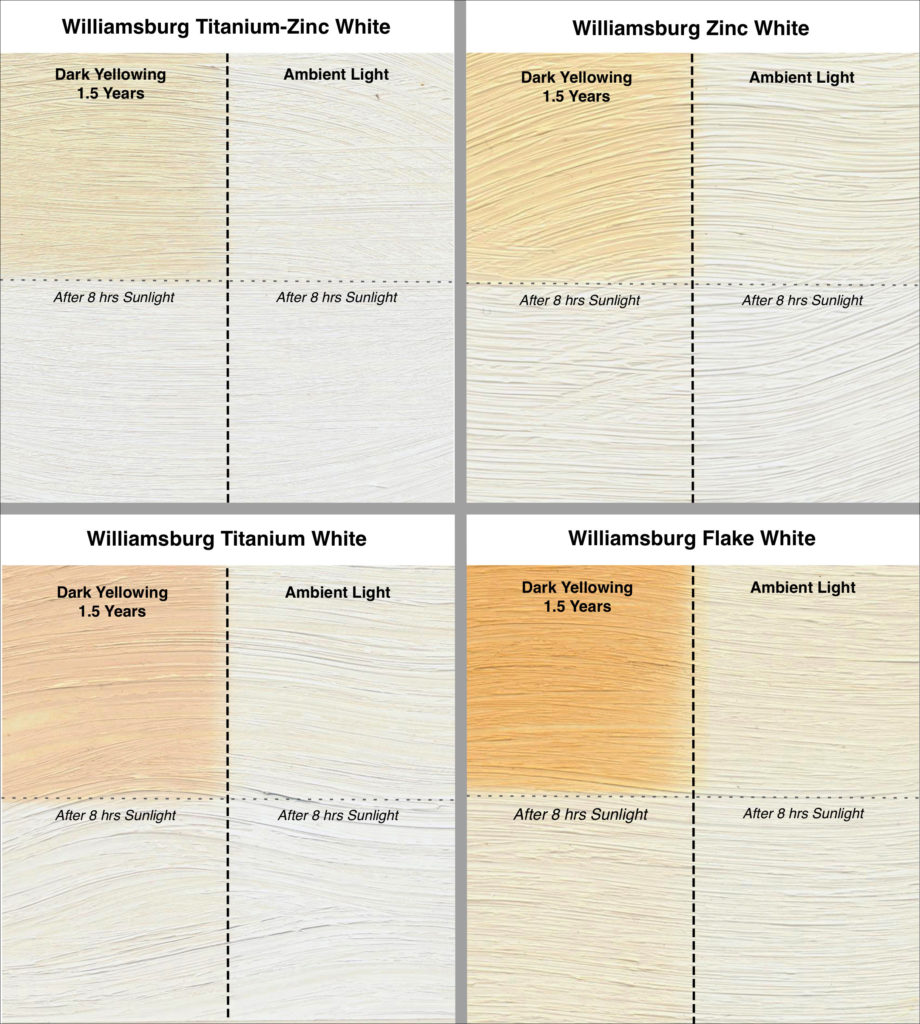

The first example arranges the four whites most painters use – Titanium, Titanium-Zinc, Zinc, and Flake – from the least to the most prone towards dark-yellowing. In each case, the left side was kept covered for one and a half years, while the right was left exposed. The bottom half of both sides was then exposed to sunlight:

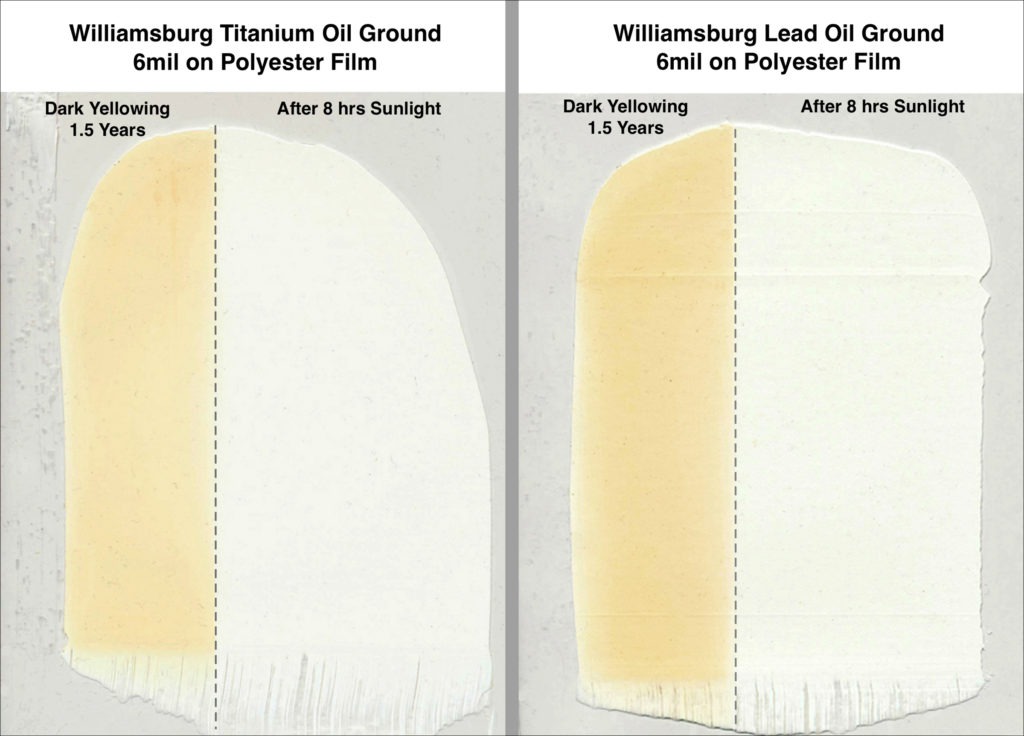

The next set shows Williamsburg’s Titanium and Lead Oil Grounds drawn down over a polyester film:

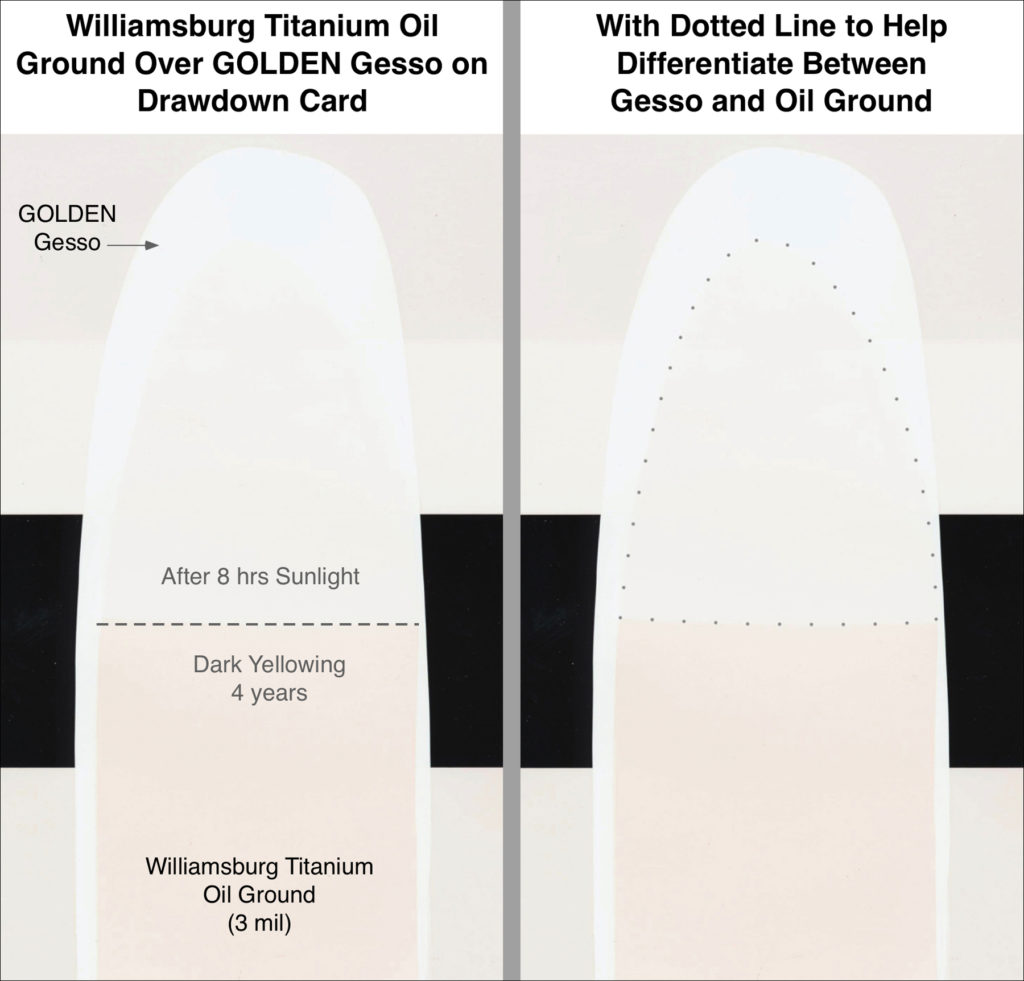

The following shows a drawdown of our Titanium Oil Ground, at a thickness similar to a heavy sheet of paper, over acrylic Gesso:

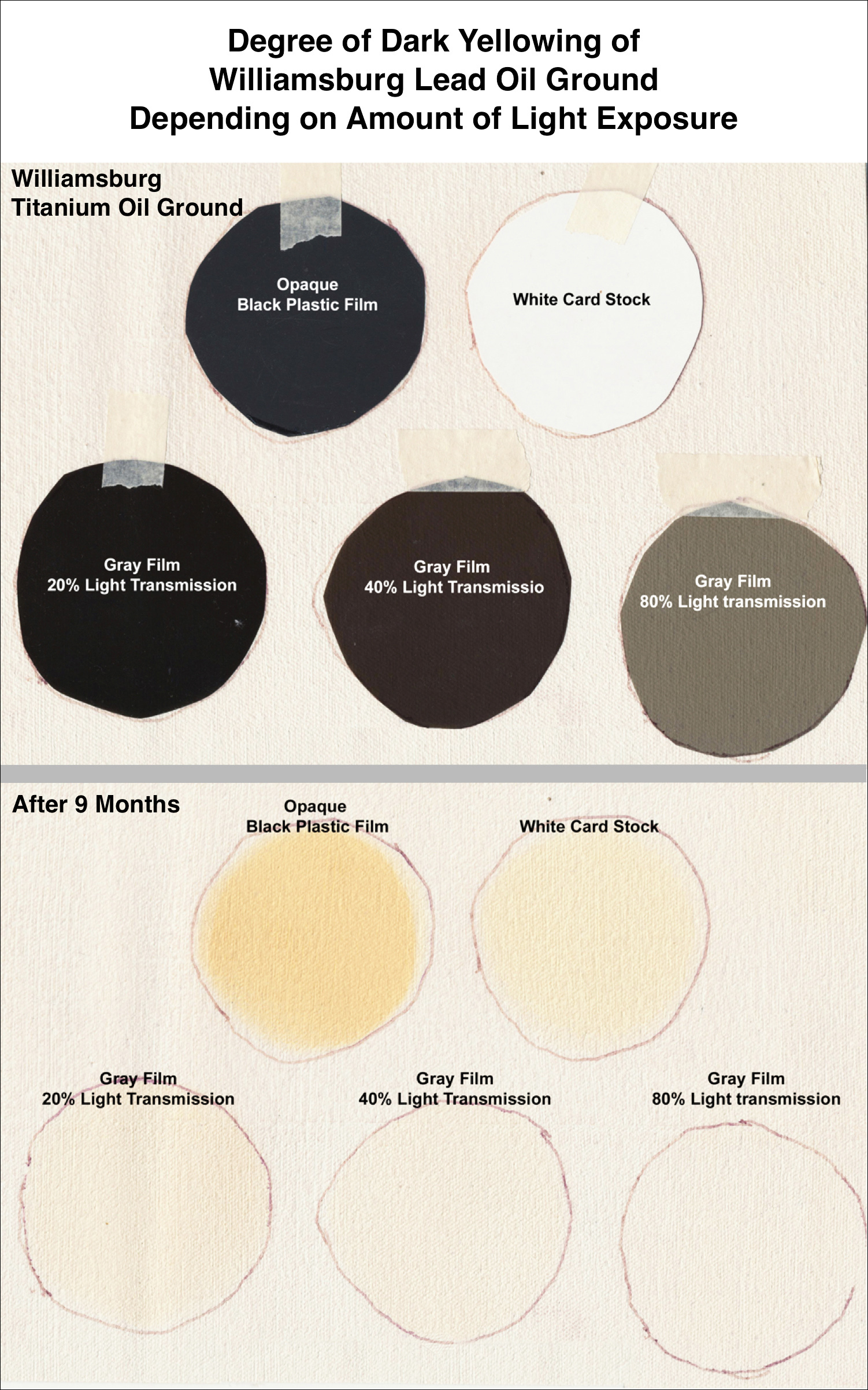

In this last example, an oil primed canvas was brought out of dark storage and covered with discs that allow different amounts of light exposure: opaque black plastic, white card stock, and three translucent, neutral gray films rated to transmit 20%, 40%, and 80% of the light, while the surrounding oil ground was exposed to 100%. After 9 months the discs were removed. You can see how the results are directly tied to the amount of light:

Recommendations

If paintings or grounds become yellowed while kept in a dark area, remember that most if not all of this is temporary and reversible. It is a normal part of the medium and something that has been well-known for centuries. To reverse or prevent these effects, follow the following guidelines:

- As much as possible, keep pieces you are working on or planning to exhibit under normal lit conditions. Try to avoid stacking or turning them against the wall for a prolonged period.

- If pieces will be packed, crated, or stored in a way that light cannot reach the surface, make sure they are taken out and exposed to light with plenty of time to recover before showing. While a minimum of 30 days would be ideal, in truth any amount of exposure will help, so plan for as much time as possible.

- It is not recommended to expose works of art to strong direct sunlight for any length of time. Bright sunlight can be thousands of time stronger than indoor illumination, with considerably higher levels of UV. While normal studio lighting will take longer to reverse the effects of dark yellowing, it is far safer. And finally, the dramatic bleaching that can be achieved by direct sunlight will not last once the piece is brought indoors and adapts to a lower level of lighting.

As always, if you have questions please email us at [email protected], or call 800-959-6543 / 607-847-6154. Or better yet, simply ask in the comments below.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

References

Henry W. Levison, “Yellowing and Bleaching of Paint Films”, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Spring, 1985), pp.69-76

Christopher Tahk, “The Recovery of Color in Scorched Oil Paint Films”, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Autumn, 1979),

pp. 3-13

Joyce H. Townsend, “The yellowing/bleaching behaviour of oil paint: further investigations into significant colour change in response to dark storage followed by light exposure”, ICOM-CC, 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon, 19-23 September 2011. p. 1-10

Carlyle, L., N. Binnie, E. Kaminska, and A. Ruggles, “The yellowing/bleaching of oil paintings and oil paint samples, including the effect of oil processing, driers and mediums on the colour of lead white paint.”, ICOM-CC 13th Triennial Meeting Preprints, Rio de Janeiro, 22–27 September 2002, ed. R. Vontobel, 328–337. London: James and James.

M. H. van Eikema Hommes, “Discoloration in Renaissance and Baroque Oil Paintings. Instructions for Painters, Theoretical Concepts, and Scientific Data”, University of Amsterdam, PhD Thesis, 2002, pp. 16-46, Accessed August 10, 2017 (http://dare.uva.nl/search?metis.record.id=194612 )

Great article Sarah!

Did you happen to look at any differences in yellowing between the main oils used (linseed, walnut, safflower and poppy) when used with those whites? I know that would make a lot more combinations but wonder if you did (or know of) any testing like that.

Hi Richard –

Thanks, always appreciate the feedback! We have looked at the dark yellowing differences of different oils, and as you might expect, the lighter the oil the less dark yellowing one gets, as well of course as less long term yellowing overall. Will add that most of our focus has been on Safflower Oil, but Poppy would be similar in performance to that, while Walnut in between those and Linseed. For one place where we share some of this is in the following Just Paint article on Safflower:

https://justpaint.org/williamsburgs-new-safflower-colors/

Scroll about a third of the way down.

Beyond just that difference in the degree of dark yellowing everything else would be the same – the ability to continually cycle between these stages, the effect of the amount of illumination, etc.

Hope that helps!

is UV l factor? If so I’m wondering about LED lights (which, as I understand, do not contain UV in their output)–whether they offer the same recovery benefit as other light sources (or, indeed) will oil pairings darken under LED ight sources without UV in the same way they would when in dark storage.

Hi Darin –

Great question. While I am not sure if having a UV component would speed the process of recovery, I am fairly certain it is not needed for the recovery to happen in the first place. I say that because the Joyce Townsend study I mentioned – as well as an earlier one by Leslie Carlyle – were both carried out in conservation studios and museums where UV would be have been filtered and tightly controlled. That said, it is certainly an area that would be great to explore a little more – again, mostly to see if UV accelerates the process, or impacts it in some other way. But for now I would not worry too much that your painting might dark yellow or not recover from dark yellowing from an absence of UV.

That’s a very informative linked article Sarah. Thank you!

I wonder then if dry past a certain point that Safflower based paints would benefit from a varnish that forms more of a barrier to volatiles escaping rather than one that is more permeable?

Hi Richard –

Its an intriguing question, and one worth testing and I’ll make a note to add that to the list. I can say that modern synthetic varnishes are generally thought of as porous and do not create tight vapor barriers. But a lot will depend on the size of the volatiles in question. A simple test will be simply to weight two identical set of films, one with and one without varnishes applied perhaps at different times, and then calculate their changes in weight over the course of many years to see how they differ and if those differences translate into measurable differences in flexibility. However, I know even in the best case we would likely not have results to share for a few years at the very least, and until then I would hesitate to recommend trying this as a strategy as there might be unintended consequences not being thought of.

Thanks for this information. I always enjoy reading about the technical side of our art work. I realize that this is outside the scope of your study, but I am curious to know if the egg tempera medium undergoes yellowing when it is placed in a dark invironment.

Hi David –

What a great question! I admit that I have never seen reference to it in egg tempera, and while egg tempera does have an oil component, it is a unique one. This might be a good question for MITRA – a website run by the conservation department at the University of Delaware and I know they have some egg tempera expertise there. You can find them at: https://www.artcons.udel.edu/mitra/forums I will go ahead and post it there and let you know what they respond – but also feel free to visit and see any response for yourself and join in the conversation.

Do you know to what extent the yellowing/darkening process is affected by the age of the paint when placed in the dark? I bought a painting last year and then left it in its packing, facing the wall, for 3 months as I was away a lot and had not got around to framing it and thought this would be the best protection. I had no idea oil paint changed tone in the dark. I was horrified when I unwrapped it and found it had gone very dark and the subject’s skin tones had been particularly affected (there is a lot of blue in the painting and it now looks dark and sludgy). I think the painting was about 4 months old when I bought it so the oil had not dried fully.

I have had the painting out of the dark for 9 months now, sometimes in a bright room, sometimes not, but it still looks dark and I am not sure it would ever go back to how it originally looked, which is quite upsetting!

Hi Lucy –

Your question is a good one and we can certainly understand how these changes would be upsetting. We do not know of any studies focused specifically on differences in dark yellowing between paint placed in the dark shortly after being applied, versus after a longer curing period. That said, a lot of the samples we have worked with do get placed in the dark shortly after being touch dry and they have always appeared to be reversible. However, keep in mind these are samples done without mediums, and usually focused on white paints versus darker blues – and those elements might make a difference in the severity of the yellowing and how fast or slow it can recover. That said, I can share that examples in my office – where half of a sample was covered with a dark opaque strip for a long period before being removed – have still not evened back out after many many months, but have definitely been slowly and clearly improving. So my guess is that your situation will be similar and, while it will entail a trial of patience, it could easily take a year or more in a moderately lit room for a color to recover. And keep in mind that in the end, short of exposing the painting to bright direct sunlight for several hours – which carries its own risks and could cause fading in any less-than-lightfast pigments – we are not sure you have a good option but to stay patient and continue to monitor the situation.

Finally, while it will not help you in the short term, I will add this issue to our future round of tests. That way, at least, we can have more information to share later on.

Were all of the Williamsburg whites (Titanium, Zinc, Titanium-Zinc, and Flake) used in the test bound in linseed oil?

Were the Williamsburg whites (Titanium, Zinc, Titanium-Zinc, and Flake) used in the test bound in linseed oil?

Hi Jack – Yes they were. Safflower oil would have dark yellowed considerably less; something we show in our Just Paint article on Williamsburg’s Safflower colors:

https://justpaint.org/williamsburgs-new-safflower-colors/

Hope that helps!

Sarah

Hi Sarah-

I’ve acquired a beautiful old painting, painted by Elioth gruner in 1926. A landscape painter from Australia. The painting has been cleaned and re-vanished with a synthetic new gloss vanish at some stage, probably in the last ten years.

The painting is flat and dull, no yellowing, the grey tones in the sky are flat and dull.

I have placed the painting in my studio with a led light on it and it certainly brings back and lightens the tones, yellowing isn’t the issue but simply its dullness.

In reading and viewing your experimental work which was so informative, would my slightly warm led spotlight on the painting help lighten the painting, or should I try controlled exposure times in full sun to lift its tones.

Best regards

Alan Moloney from Australia.

Hello Alan,

Sarah is away on sabbatical for the year. I am happy to reply in her absence.

It may be possible to reverse dark yellowing with LED lighting. The article in the Reference section above, written by Joyce Townsend, does indicate that dark yellowing was observed to reverse with UV free exposure. Although putting your painting in controlled exposure of direct sun might be effective in reversing dark yellowing, it is probably best to keep it inside under the lighting conditions it will continue to be viewed under. That way it will slowly come to the level of brightness those lights have the capacity to maintain. In the case of an older painting where the pigments are unknown, it is better to err on the side of caution and resist the urge of exposing the work to direct light.

We hope this helps. Congratulations on your new acquisition!

Greg Watson

Hi,

Does the mixing of alkyd mediums with oil paint inhibit dark yellowing? I don’t suppose it does but I did wonder…

Thanks

Hi Andrew,

It doesn’t seem to make an improvement as far as we can tell. If you have a couple different alkyd mediums you are curious about, it would be an easy test to perform. Simply make a mixture with the resin and white paint, apply it to two of the same surfaces, allow to fully dry, then put one of the surfaces in the dark and leave the other in the light. You should start to see some dark yellowing results in a couple weeks – month. Let us know how it goes!

Best,

Greg Watson

I’m working on a house built in 1833 and recently demolished a built-in desk installed in the 1960s. The trim behind it is old enough that it predates the plaster and is held on with square-headed nails, so I’m guessing that it is original to the house, but the two paint layers– a dark greasy cream colour over a dull pale mustard– don’t mesh well with my understanding of what colours would have been common and popular when they would have been applied. The corresponding wall colours are limewash white, followed by a warm shell pink that doesn’t look -terrible- with the cream, but it is kinda… eh. I found this article while looking for information on whether the pigment in the pale mustard colour might have faded and what colour it might have been originally, but now I’m wondering if the cream might have originally been white. It certainly looks better that way in the digital rendering.

Hi Paul –

Sorry for the delay in responding! Great questions and so glad you found this article as it absolutely is a factor and any paint from that period is going to be particularly susceptible to dark yellowing. Also, be very conscious that you are likely dealing with lead-based paint, and so concerns over toxicity become a major factor. You should consult with your local building code department to see about testing for lead and, assuming positive, how to handle the issue when restoring/remodeling an older home. In terms of color, however, an old dark yellowed white paint can appear literally as anything from a deep cream, to light tan and even brown beige color. Which you can see in the pictures in that article, as well as examples in this one: https://justpaint.org/on-the-yellowing-of-oils/

Hope that helps and if you have any other questions let us know.

Best – Sarah

So the yellowing of Oil paint has two part?

One is kind of permanent. And one is the largely reversible “Dark Yellowing”.

I guess i have underestimated some paint, cause the test sheet is stored in darkness / against the wall (for avoiding dust).

Yes that is correct. And it seems that the longer a painting is allowed to cure in exposed air and light, the better the color will remain over the long term. We have seen samples that are stored right after they dry to never recover to as bright and pure a color as ones that have remained out since they were created. both will dark yellow if put into storage, but the one that cured longer in the light will be less yellow over the long term…or so it seems.