It’s been a problem for a very long time. At least according to the historical record. Blotchiness. Sinking in. Dead spots. For oil painters these are well known terms, conjuring up images of skin disease as much as painted surfaces, but whatever words are used the implication is clear – it’s an undesirable nuisance; a loathsome interloper in the creative process.  As for what to do about it, the traditional and handed down remedies have run the gamut from oiling out with different recipes to the frequent application of retouch varnishes of various types. What is the current thinking about all this? What might be the cause and best solution? What follows is not an exhaustive treatment on this topic by any means, but it shares results from some current testing and offers what we feel are best practices given what is currently known.

As for what to do about it, the traditional and handed down remedies have run the gamut from oiling out with different recipes to the frequent application of retouch varnishes of various types. What is the current thinking about all this? What might be the cause and best solution? What follows is not an exhaustive treatment on this topic by any means, but it shares results from some current testing and offers what we feel are best practices given what is currently known.

The Problem in Short

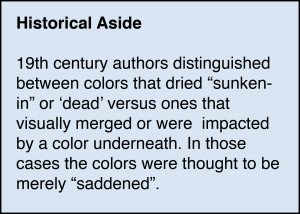

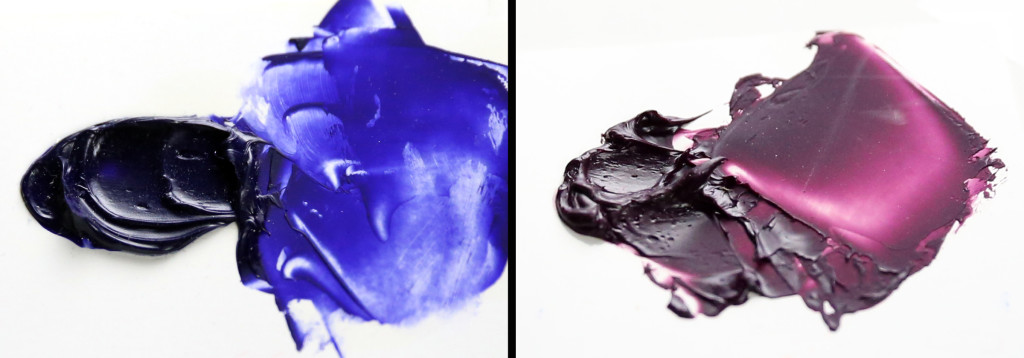

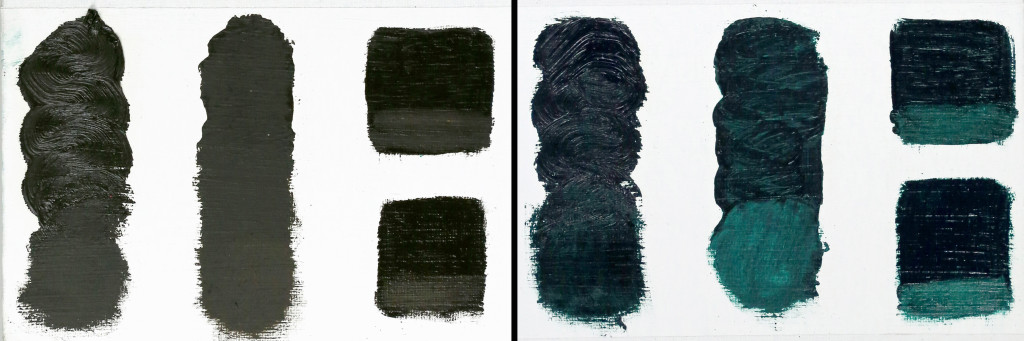

Before heading toward causes and cures it’s good to briefly define the problem, especially if this issue is new to you. What is being described here is the appearance of a dull matte area in a section of an oil painting. Thus the sense that the color has “sunken-in”, or gone “dead”. This is particularly annoying with darker colors, where their matte appearance makes them seem lighter and creates the problem of matching a color with fresh, glossier paint much more difficult (Image 1).

Causes

Absorbent Grounds and Solvent Use

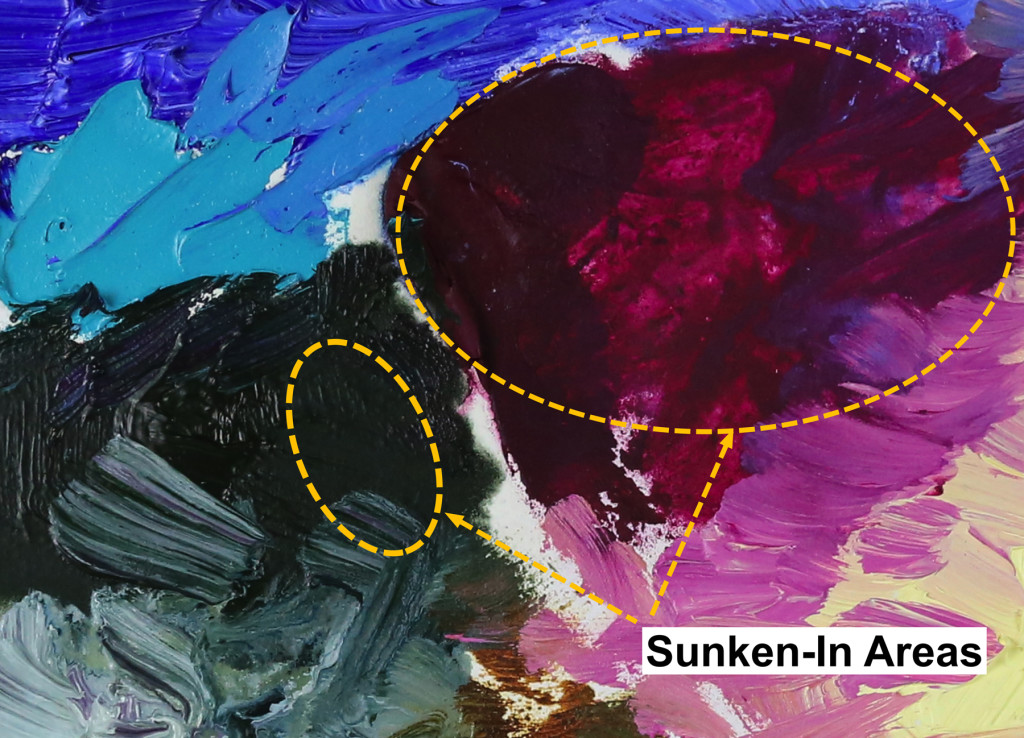

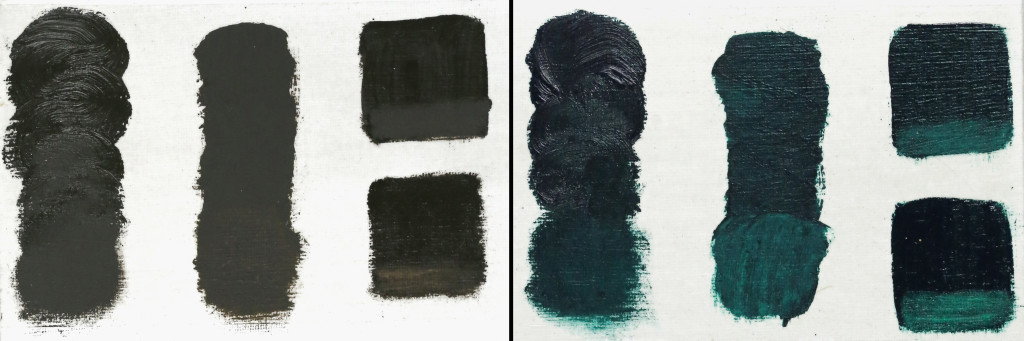

The most common chorus as to the causes of sunken-in patches of paint tends to focus on two areas – overly absorbent grounds and paints thinned with too much solvent. And of course these are two faces of the same coin, as both imply that the paint has become underbound to some extent: in one instance, by the oil being pulled down into a thirsty, matte surface, while in the other being spread out too thinly and readily soaking into the underlying layer. We wanted to put both of these causes to the test, so painted various swatches over an assortment of grounds, including GOLDEN Gesso, Acrylic Ground for Pastels, Absorbent Ground, and Williamsburg Titanium Oil Ground and Lead Oil Ground. For paints we chose Raw Umber, a color commonly associated with sinking-in, and Phthalo Green, which dries to a reliably glossy film like most synthetic organics. These were applied in various ways: thickly brushed out, blended with odorless mineral spirits to the consistency of cream, rubbed out with a cloth or cotton swab, and finally, mixed with a fast drying alkyd or Stand Oil as a glaze (Image 2).

Very Thin Applications

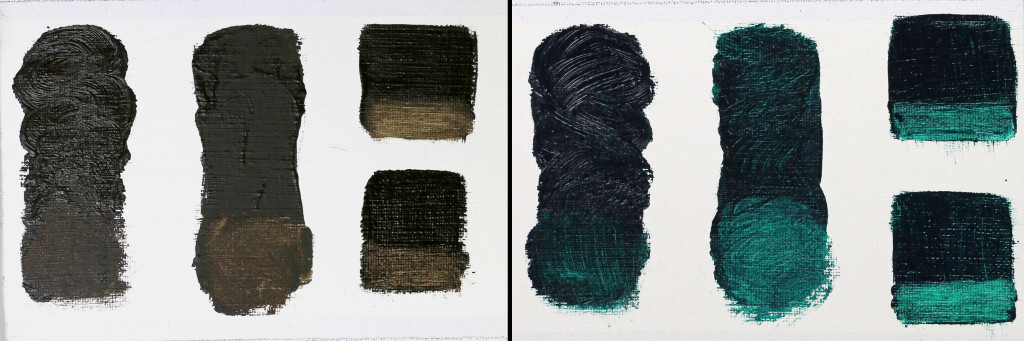

A third cause needs to be mentioned, which functions independently of a grounds’ particular absorbency; namely film thickness. For many paints, it turns out this alone is enough to cause a matte appearance to develop, as you can see in the following examples.

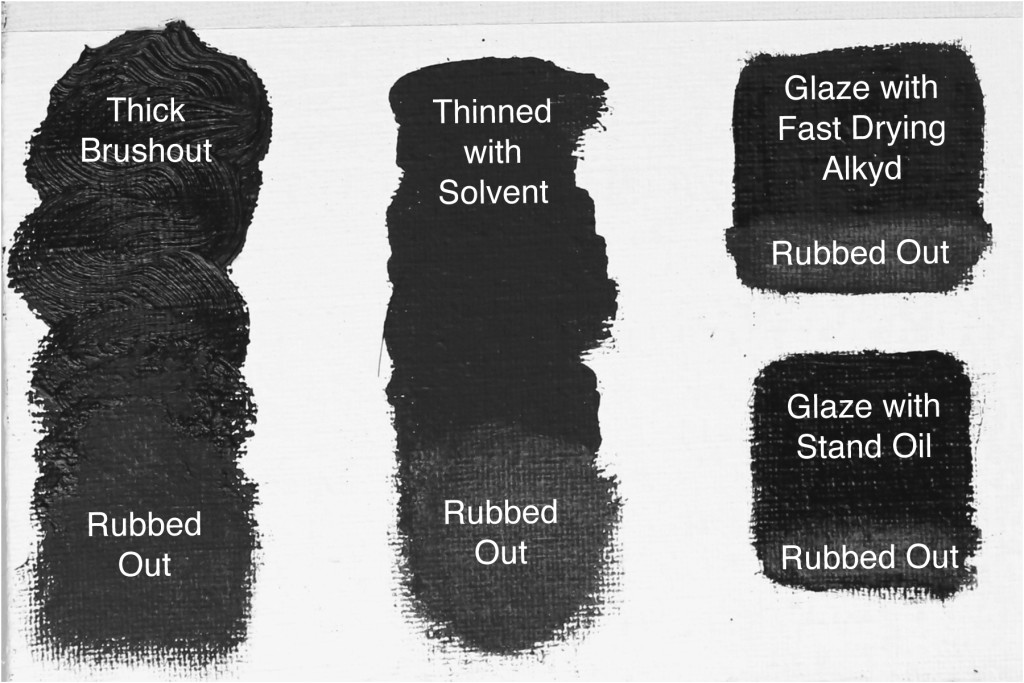

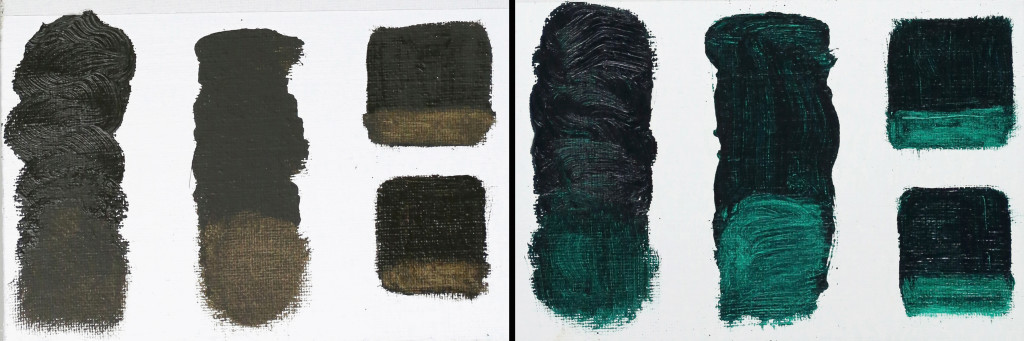

In the first one (Image 3) we applied Raw Umber and Phthalo Green in three different thicknesses onto a non-absorbent polyester film. Sheen is notoriously difficult to capture in a photo, but if you follow the reflections across the curved surface you can see changing degrees of gloss. For Phthalo Green, the gloss actually increases the thinner the paint is applied. Raw Umber, on the other hand, grows increasingly matte and in a very thin film, has a nearly dead flat appearance. Since none of this can be caused by absorbency, and Phthalo Green has even less oil by volume than Raw Umber, the only possible explanation is that the particle sizes of the different pigments have a large impact on the final sheen of the paint, especially when applied very thinly.

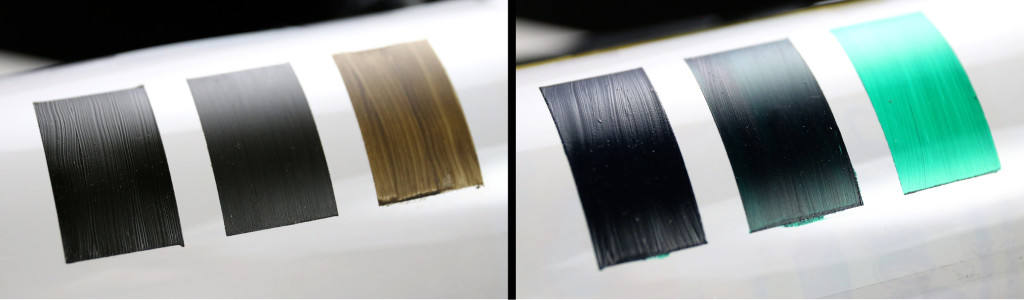

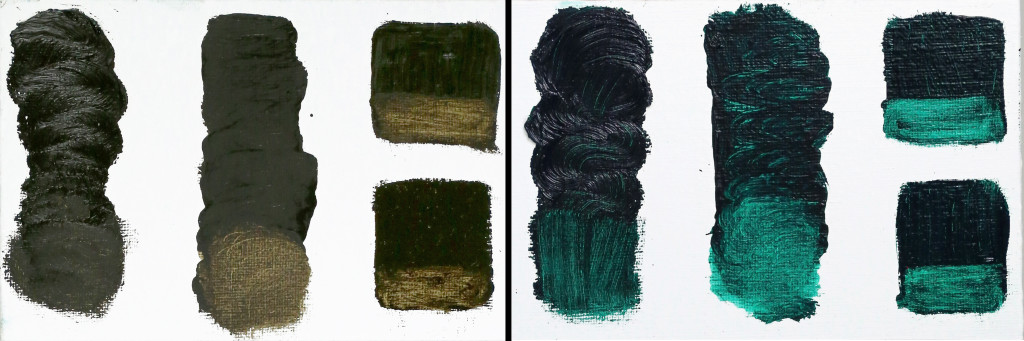

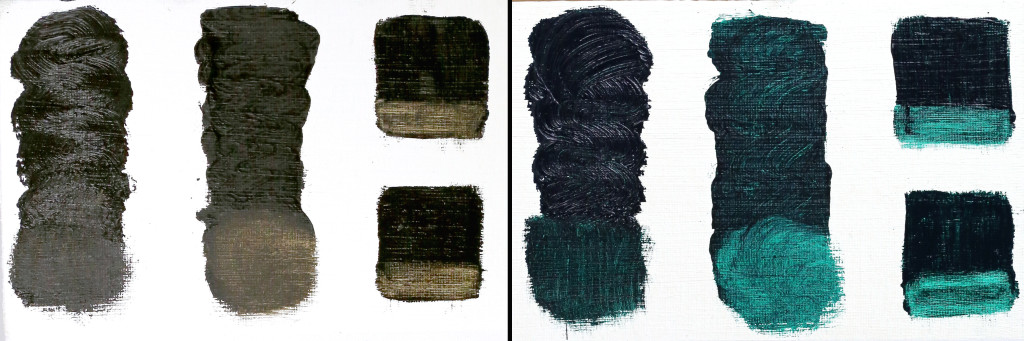

The second set of examples (Image 4) are simply two thicker piles of paint that were then scraped with a palette knife to create a thin film on a lacquered, non-absorbent drawdown card. In both cases the glossiness evident in the body of paint is lost in the thin scrape-out, where the thinner the paint the more matte the appearance. In fact, at its thinnest, the paint takes on an almost powdery appearance.

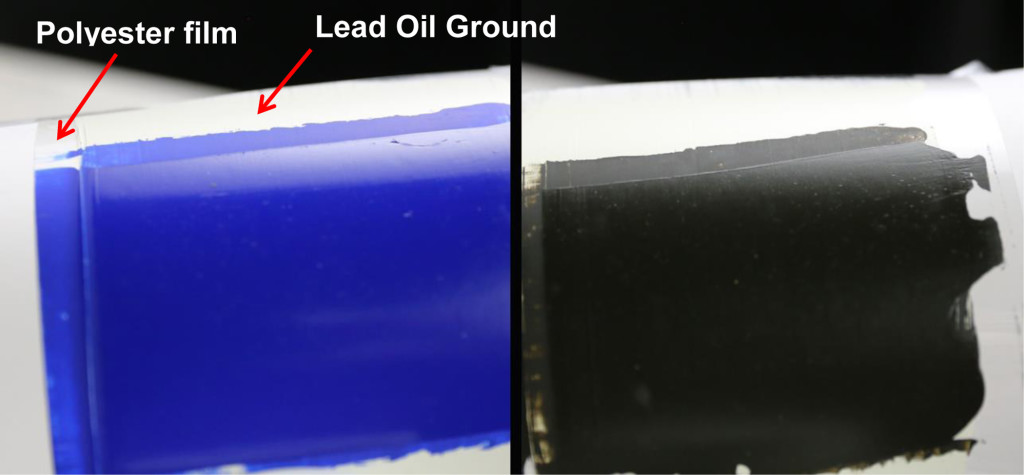

In the last example (Image 5) we show Cobalt Blue Deep and Raw Umber cast over Williamsburg Lead Oil Ground on polyester film. These are both cast at 6 mil thick, about the same as two sheets of paper, and clearly show the degrees of gloss you would expect for a well bound film. The thin, very matte strips to the top and sides are areas where the paint was scraped very thinly by the drawdown bar during application. The bands to the left are on the polyester film, while the ones on top are on the Oil Ground. This is important as it shows that the dead matte appearance is independent of any difference in absorbency between the Oil Ground and polyester film. Again, the only explanation is that the paints, when applied very thinly, can have the same appearance as a “sunken-in” area usually attributed to solvents or an overly absorbent surface.

Test Panel Results

Paints

While only including two in this testing, they performed as expected, with Phthalo Green creating a glossier film in all instances, even when thinned with solvent to a very fluid consistency and applied on an extremely absorbent ground. As Phthalo Green has less oil by volume than Raw Umber, this is clearly a function of pigment particle size more than anything else.

Grounds

It’s important to note that the connection between absorbent grounds and sinking-in stretches well back into the historical record, with documents recording artists bemoaning, complaining and finding fixes for grounds they felt were too absorbent. At the same time, a seemingly equal number pursued them with fervor, especially during Impressionism and other periods when a matte surface was actually prized and thought to give a more direct, brighter, and less yellowing appearance. So this is not a new issue that can be easily hung at the door of modern formulations or materials, but rather a common one known to occur with even the most traditional materials of the highest quality.

GOLDEN Acrylic Gesso (both 2 and 4 coats)

Overall, while slightly more absorbent than the various oil grounds, the word slightly needs to be emphasized. Neither application was anywhere near the extreme absorbency conjured up by so many on forums and discussion boards. That said, these tests only included our own brand, and sadly acrylic gessoes have become a category with a notoriously broad spectrum of quality and performance in the marketplace, with many being overly absorbent and even brittle due to excessive amounts of fillers and water. In the results, 4 coats did better than 2, feeling less absorbent and performing closer to an oil ground. However, wiping paint away was not as easy as with oil grounds, something that is frequently noted. (Images 6 & 7)

GOLDEN Acrylic Ground for Pastels / GOLDEN Absorbent Ground

In feel and performance these come closest to various traditional absorbent grounds, such as chalk gesso. In all applications Raw Umber had areas that were sunken-in, especially where wiped away or thinned with solvent. It clearly did best when Stand Oil was added. Phthalo Green, on the other hand, did okay – not as well as elsewhere, but clearly able to hold onto some luster and, with added mediums, able to maintain a glossy sheen even in a thin glaze. Please note, while included in these tests, the Absorbent Ground Tech Sheet cautions against the use of full-bodied oil paint applications as the extremely porous surface can absorb too much binder, leaving the paint sunken in or, at worse, underbound. (Images 8 & 9)

Williamsburg Lead Oil Ground, Williamsburg Titanium Oil Ground

Both performed well, with minor differences mostly related to their sheen. The glossier Titanium Oil Ground allowed for glossier paints overall, although rubbed-out and solvent-thinned applications of Raw Umber still appeared blotchy and dry when no mediums were added. Phthalo Green, on the other hand, appeared glossy on both, even in the rubbed out areas. (Images 10 & 11)

Mediums

On absorbent surfaces the Stand Oil generally did better than the more fluid alkyd medium, its thicker consistency allowing for better hold-out and resistance to soaking in. However the Stand Oil, as expected, also dried more slowly.

Solutions to the Problem

In the past it was common to deal with this problem through the use of retouch varnishes or various recipes for mediums that were applied in order to resaturate the matte areas and help with color matching when starting to paint again. Unfortunately these were often extended over the entire painting, creating issues later on for conservators as these layers would yellow badly as they aged and, in the case of varnish, grow brittle and remain sensitive to solvents. In light of that, current recommendations are much more targeted and simple.

Initial Considerations

In general, oiling out is not recommended. However, if you choose to oil out your painting we recommend you follow the steps outlined in the “Best Practices” section below. If you are finding that you frequently need to oil out your painting it is best to consider the following factors that are likely at the root of the problem:

- Your ground may be too absorbent. Try experimenting with different grounds to see if this helps prevent your oil paints from sinking in.

- You are adding too much solvent to your paint. Try to avoid using too much solvent or even any solvent at all.

- You are using paint with a high pigment to binder ratio. Some paint formulations may inherently have a low concentration of binder. Try adding a touch of oil medium to your paints to help maintain sheen and body.

Best Practices

Repaint

If possible, repaint a sunken-in area with the same or similar color but this time add a small amount of a bodied oil, such as Stand Oil, which should prevent any further sinking in and, as a result, should dry with a soft but even sheen.

Oiling Out

When repainting is not possible or practical, one can apply a small amount of a drying oil only to an area you plan to work into, making sure to wipe off any excess. Preferably use the same oil or medium found in the paints or in that section, applying as little as possible and using only enough to even out the sheen. Never extend this treatment to the painting as a whole, or to areas that will not be painted over in that day’s session. Doing so can create problems with adhesion and the eventual darkening and yellowing of those areas.

Adding solvent to the oil to create a thinner application, or thinning something more viscous like Stand Oil, is possible but care must be taken as young oil films can remain solvent sensitive, especially when underbound. In addition, solvents can extract materials from the film and make it more brittle over time.

Varnishing or Retouch Varnish Used at the End

This can take patience and try nerves, but if experiencing dead areas after a painting is finished the best thing would be to wait for it to dry sufficiently to allow for a final varnish. Waiting 6-12 months remains the safe rule before varnishing, and while there are some who advocate a shorter period, we feel there has not been enough research done on the possible consequences. That said, if needing to apply something earlier, after making sure it is at least hard dry, the use of a proper retouch varnish would be preferable. These are typically composed of thinned-down versions of full strength varnishes and should be applied as thinly as possible, aiming to simply create an even overall sheen. Damar and other natural resin varnishes should not be used for this purpose due to yellowing and embrittlement.

Not Recommended

Retouch Varnish Used in the Process of Painting

Despite the name, this is not recommended as a way to remedy sunken-in areas of color during the course of a painting. Doing so complicates the structure of the piece by introducing a very different material in between paint layers, not to mention that retouch varnishes are almost always removable and therefore poses a problem for future conservation and cleaning as they could be reactivated. That said, if you have used these, simply make sure to make note of it on the back of your painting.

Mediums or Oils as a Final Layer

DO NOT USE. More than any other practice, this is likely the worst option as it introduces a permanent layer of oil that will only darken and yellow with time and with few treatment options available to reverse this condition. Also, should you need to paint on it further, the dried layer of oil or medium could cause issues with adhesion, beading, and potential problems with cracking in the future.

Thank you for doing this study . I have a painting with dark dead areas right now, but I still love the painting.Waiting for it to dry and varnish will fix it.

Some paint colors are notorious for being dull, so now I know what to do with Stand Oil.

thank you.

Hi Donna – We are so glad you enjoyed the article and found it useful! Dead spots can definitely try one’s patience when waiting for a painting to dry enough to varnish, but ultimately that really is the best way to even out the sheen. As always, if there is anything else we can ever do, just let us know. Until then, best of luck with all your painting!

Thanks for this. Since I have never gone to school for art, I wasn’t sure what the stand oil was even for!

Hi Suzanne – You are so welcome! And thank you for taking the time to let us know that you enjoyed the article. Stand Oil is indeed useful as it yellows much less than regular linseed oil while also helping the paint to level, besides also helping with dead spots. Just keep in mind it dries slower than most oils, but then oil painting is nothing if not a constant reminder that ‘patience is a virtue’. As always, if we can do anything else, just let us know!

Great article. I will share.

Thanks! We appreciate it!

Thanks Sarah! I cannot paint without oiling out. If I skip this crucial step, then I’m astonished at the nasty surprises that suddenly appear upon varnishing. These surprises had ‘sunk in’ and were not visible during the painting process. I find that oiling out is like a “dress rehearsal” for the final varnishing. It reveals the unseen and indicates what the final painting will look like. But there is always the issue of time. I can’t use slow-drying oils and still complete a painting in a reasonable time frame. Finding a fast-drying oiling out medium is challenging. Some painters abuse fast-drying alkyd resins by oiling out with them. I know of painters who begin a day’s work by applying a layer of Liquin over their work. Few of them realize that this is precarious. It would be great if manufacturers could produce a fast-drying “Oiling Out Medium”. Sadly, this isn’t an option. Thickened Linseed Oil is too viscous for me, even when diluted with a solvent. I’m tempted to try Drying Linseed Oil as an oiling out medium, perhaps diluted with a solvent. How does that sound to you Sarah?

Hi Alex –

Unfortunately I am in Peru until June 6th so cannot go into much depth at the moment. Long and short oiling out over areas you will not paint on shortly afterwards is not supported by conservation research as they have had many old paintings that are irreparably yellowed or have other issues as a result. The best thing to do is to adjust your ground, painting techniques, and possibly the type of medium used to limit the amount of sinking you are having.

As for fast drying mediums, oil painting is ultimately a medium that rewards patience and taking shortcuts almost always entails a lot of additional risks. That said, something based on Stand Oil with an alkyd to help speed drying, and OMS if needed, is perhaps the best I can offer.

I know that is not an ideal answer for your needs but is really the best practice we can recommend.

Hope that helps. If you need more assistance I will be back on June 6th.

Thanks!

Thanks Sarah – as usual you go the extra mile! Enjoy your time in Peru, because I will be bugging you again after June 6! Regards.

I thought final varnishing doesn’t do much to remedy sunken passages? Or if it doesn’t it’s only temporary?

Hi Jay –

If the painting is fully cured final varnishing should help to even out the sheen and fix any sunken-in passages. After all, retouch varnish, which has its own long history of use as a curative for sinking-in, is simply a weakened, dilute solution of a full strength varnish. So the practice of using varnishes to fix this issue is a well known, traditional approach. It is also important to always start with thin layers of gloss varnish until an overall even sheen is established, and one might need to start with a thin application on just those areas with dramatic sinking-in for a more even final result. Lastly, we think its important for the painting to have ideally dried for the traditional 6-12 month period to assure that it is no longer undergoing many changes and has become ‘hard dry’.

Hope that helps!

Thank you very much for this work, which has much more depth than anything I’ve read on the subject before. I have a question about oiling out to remedy sinking. I understand why this is a bad idea with linseed or an oil that is known to yellow, but what about oiling out with safflower or another type of oil that isn’t going to yellow? Or, is the long term problem caused by the fact that a layer of oil (regardless of type) will attract dirt which will cause it to yellow, and it won’t be removable as a varnish would be? I’m really trying to find a combination that will work in the short and long term. I don’t want sunken areas if a painting sells quickly or is a commission that the client doesn’t want to wait 6-12 months for, but I also don’t want to jeopardize the future of the work. I have been using a thin layer of alkyd to oil out, but am rethinking that thanks to this information.

What do you think of oiling out sunken areas with safflower (with or without a little alkyd in it), even if I’m not going to repaint those areas, and then varnishing later when the time is right?

Also, retouch varnish often seems to remain a little bit tacky, and that makes me distrust it, so I don’t think that’s a good solution anyway.

Thanks again for your help and advice.

Hi Kathryn –

Thanks for the warm words about the article – we truly appreciate it! And great questions – which I try to answer below:

Q: I have a question about oiling out to remedy sinking. I understand why this is a bad idea with linseed or an oil that is known to yellow, but what about oiling out with safflower or another type of oil that isn’t going to yellow?

A: While Safflower will definitely yellow less, it will STILL yellow some over time. So one is not completely rid of that issue. Plus Safflower oil makes a less durable and more brittle film, so having it as a permanent coating on top of the paint, or in between layers, is not necessarily ideal. That said, if you are oiling out IN ORDER to resume painting on top, and have been using Safflower oil in your mediums as paints, then using Safflower oil as a way to remain consistent would have some validity.

Q: Or, is the long term problem caused by the fact that a layer of oil (regardless of type) will attract dirt which will cause it to yellow, and it won’t be removable as a varnish would be?

A: Yes to all of these things.As the article points out, one should oil out ONLY in areas you plan to paint back into, and not as a continuous overall coating left alone. Obviously when painting on top of an oiled out section, these other issues are not a factor.

Q: What do you think of oiling out sunken areas with safflower (with or without a little alkyd in it), even if I’m not going to repaint those areas, and then varnishing later when the time is right?

A: It is not something we can approve or recommend, and we know that no conservator or materials expert would present this as best practice. So that’s the short answer. That said, if having to use something, then a retouch varnish would be better than a general oiling out since it is at least potentially removable and should not yellow appreciably if art all. So if you have to do something, that would be the best option in our opinion.

Hope that helps and if there is anything else we can do, just ask! Also, feel free to email us with questions at [email protected].

Sarah

Great article, but now I am totally confused on best practice. Based on your research it shows oiling out is bad, so that makes me wonder why would a company like Gamblin advocate to oil out for every painting? https://www.gamblincolors.com/controlling-surface-quality-a-holistic-approach/

They even say it is part of having a more stable painting in that article. And when people glaze (say with liquin or galkyd) wouldn’t that then not be ideal for a painting top surface before varnishing? Clearly those oils or safflower oil like you mentioned above will yellow over time even if it has color in a glaze?

Curious to hear your thoughts. Thank you

Regards

Matt

Hi Matte – Thanks for the comment and glad to hear that the article was helpful, even though it seems to have raised as many issues for you as it resolved.

A few things to note – we DO include oiling out among “Best Practices” but feel it should be used judiciously and only when and where needed, rather than applied as an overall layer. By using it only where you plan to repaint that day, any oil left on the surface after wiping away the excess would simply merge and be part of the whole and not represent a truly separate, intervening layer. On the other hand, applying oil over areas where it is left to dry on its own runs the risk of additional yellowing and darkening in the future, and if ever needing to paint over those areas later on, there could be potential wetting and adhesion issues. Granted a lot of this is an issue of degree and we are choosing to ere on the side of caution, especially as we know conservators who have been confronted with older paintings where the broad use of oiling out caused issues with no good solution. As for glazing, this is great question. Certainly using all over,glazes with very little color will run the same risks of yellowing and make subsequent painting in those areas difficult. A lot of the yellowing of glazes is not noticed in many older paintings because they were frequently used to deepen and develop the darks, or to provide warmth to an area that then simply grew warmer still – the resulting patina even being, at times, prized, like the admiration we have for old furniture. So its complicated.

Overall our philosophy is to keep things as simple as possible and avoid as many intervening layers of oil or – even worse, varnish – as possible. But art is always at least partly a dialog and tug-of-war between artistic necessity and technical soundness.

As for Gamblin, we cannot speak to their positions and at the end of the day we simply have a difference of opinion or philosophy on some issues. Overall we are known to err heavily on the side of caution and, as best we can, to follow what we consider ‘best practice’ in light of current conservation research. That said, conservation is a large and evolving field and finding consensus, even there, is a rare thing.

Hello Sarah, good morning. I came across the problem of dead dry patches when applied linseed oil to my finished painting before varnishing. I see a few dry patches that do not get leveling shinning as most of the painting seems leveled with “oiling out”. My question is how to fix this problem before I apply varnish. 2nd question, how long do I have to wait before applying varnish after this application of linseed oil used as “oiling out” process?

Reading your article I did learn that I will be using retouch varnish just to be on the safer side. Thanks.

Hi Meera. Thanks for the great questions. As you can sense in our article, we recommend oiling out only when needing to alter the sheen of an area one will be painting back into and never as a final finish on its own. In terms of evening things out once a painting is done, one of the uses of varnishing is just that – to unify the sheen over the painting, and so one would typically just apply sufficient varnish to achieve that or, if needed, to start with a light spot application of varnish to a sunken in area and then follow with a more overall application. Finally, in terms of how long to wait, we take a very conservative approach and recommend always waiting 6-12 months after the last layers are applied – including things like oiling out. If you do not have that luxury of time, then we would obviously encourage you to wait as long as possible, with perhaps a month being a good minimum. But sadly there is not enough testing around this to be precise. Using retouch varnish will also help limit issues of applying varnish early on, so would agree that is the better option.

Hope this helps and if we can do anything else just ask!

Hi Sarah,

Thanks so much for this insightful article. The darker areas of my painting developed a cloudy and matte appearance. I believe the colors have sunken in. The color was a rich dark brown (mixture of Ivory Black, Rublev Purple Ocher, Yellow Ochre Deep and I think English Red), and I thinned it with refined linseed oil to create a thin layer for my shadows. After reading your article, I think the thin layer may have been the source of the problem.

My question to you is, how do I fix this problem and bring back the richness of the dark brown? If I were to repaint, would I need to paint a thicker layer? Or would I need to change the medium to maybe stand oil + Gamsol? If I were to use varnish instead, would I need to apply retouch varnish first to the sunken in passages before I apply a final varnish to the whole painting? How long would I need to wait between applications of retouch varnish and final varnish? Could you recommend a good retouch varnish and final varnish?

Lastly, how do I avoid this sinking in for future dark passages? Is the solution painting a thicker layer with less medium? Or continue to paint in thin layers but with a medium that includes stand oil?

Thanks so much in advance for your help!

Hi Annie –

Thanks for the comment and questions. Fist definitely know that the blend of colors you used included many that have long reputations for drying unevenly, so you are not alone! And definitely if you found that applying a thin layer with the first medium resulted in dead areas, then switching to one using a bodied oil, such as Stand, could be helpful since it will not soak into the underlying layers as readily.

As for how to correct things, if repainting is an option then that would be great and yes, using a medium with Stand Oil – as mentioned above – can help. As for painting it more thickly, you might not need to. What we would recommend is first oiling out the areas where you will repaint using a blend of Stand Oil thinned with some Gamsol and letting that sit for a bit before wiping off any excess. This will help quench the thirst of the sunken-in areas, so to speak, and should allow the new layer to dry more evenly. If not wanting to repaint, then you could correct this when you decide to varnish – but know that we recommend waiting 6-12 months after a painting is finished before applying a final varnish, so this might not be an option if you have just recently completed things. For future reference we make a series of varnishes that are compatible with oil paints, called MSA Varnish, that would be worth looking into:

http://www.goldenpaints.com/technicalinfo/technicalinfo_msavar

Or take a look at the varnishes put out by such companies as Gamblin, Natural Pigments, or Winsor Newton as all of these would be possibilities.

Lastly, to avoid this problem in the future, you might want to check to see if your ground is too absorbent. Not knowing what you are using it is hard for us to say if you need to change. If using an acrylic ground, or a preprimed canvas, you might look to first apply an oil ground to the surface which can help by often being less absorbent overall. Then tweaking the medium you are using, by adding or swapping in some Stand Oil can also help. In truth painting processes are so individual and dependent on the stage and the colors being used, that it is hard to give a one-size-fits-all recommendation. And keep in mind that the article is not against oiling-out as a practice – and one that is often needed – just cautioning painters to not use it as a final coating. but if you get sinking-in from earlier stages, when one’s painting is often less rich in medium and one might use more solvent and paint more thinly, then oiling-out before developing those areas further is perfectly fine.

Okay, I hope the above helps and as always, if there is anything else we can do, just ask!

Dear Sarah,

Thank you so very much. Your article is extremely helpful and informative.

Hi Fronc –

You are so welcome! It is our pleasure to help and if we can ever do anything else just ask!

Best –

Sarah

Hi Sarah, great and informative article. I have a question that might only be slightly about this article but you seem very well versed about materials and methods so I’ll give it a go here. About 10 years ago I did an underpainting on a large painting using a medium consisting of dammar, stand oil and turpentine. I haven’t touched it since. Now I am finally ready to continue but really dislike using turpentine these days. What medium and method would you recommend. I am using walnut oil as a medium these days and was wondering if there would be any adhesion issues if I would over paint using only that. Do I need to “wake up” the dried layer by oiling out with a turpentine and walnut or stand oil layer?

Thanks –

Dan

Hi Dan –

One can definitely paint on top of an older very well cured oil painting, although a few words of caution are in order:

– first, there is a risk of pentimenti appearing whenever painting on top of another image. Essentially oil paint becomes more transparent with age, so darker areas of an underlying area can frequently come through – even if only faintly – with age.

– because you already have a paint layer down, you should not use thinned-out washes at this point as you will go against the general advice of ‘fat over lean’.

– if there are areas that are very smooth or glossy, they will need to be sanded to help provide some tooth for subsequent layers to grab onto. The ideal would be if the painting has an overall matte to semi-matte appearance.

We do not think you need to oil out the entire painting to ‘wake it up’, but if you are painting into a specific area, then oiling out with just a small amount of Linseed, or Stand Oil with some odorless mineral spirits, can be helpful in terms of paint handling and color matching. Just make sure to thoroughly wipe off any excess before painting, leaving just the thinnest and barest of layers to work into.

As for a medium to work with, there are a number of alkyd-based ones that are popular, if wanting something that dries quickly. Within the Williamsburg line, we do sell an Alkyd-Resin (Slow Dry) that can be used in place of Dammar and Stand Oil in medium recipes, or simply thinned itself with Odorless mineral Spirits. In general we believe that the less medium you can get away with the better, so use whatever you choose sparingly. This will avoid a lot of the complications in drying, prevent excessive yellowing, and simply keep[ things….well, simple!

Hope that helps!

Best –

Sarah

Thank you for this information. I begin my paintings with thinned Burnt Umber, usually using Linseed Oil and sometimes Gamsol as well. I have problems with sunken in areas and have tried various solutions to deal with it. Although I’ve painted for a long time, I’ve never used Stand Oil as I wasn’t sure how to use it. For a short time I switched to Walnut Oil, but then had problems of it running after I had painted it and it was slow to dry. So I gave that up. Thanks for your research into a complicated issue!

Hi Laura –

Thanks so much for warm words about our research! In terms of your own issues, Burnt Umber is definitely one of those pigments that can be prone to appearing sunken-in or matte when applied thinly. And definitely, as the article mentions, Stand Oil can help a lot with the problem – either by adding small amounts into your paint, or using it when needing to oil out a section you plan to paint back into. Just make sure to use it in moderation, keeping in mind that Stand Oil dries more slowly than regular linseed oil. Hope this helps and let us know how your future painting goes.

Best –

Saraah

Hi Sarah,

Thanks for the Great article addressing this common yet frustrating problem with oil paint. I paint with mainly natural earth pigments and I tend to add a small amount of bodied oil to my colors which helps remedy most of my sinking in. I find that my very first layer of oil paint hardly ever sinks in. It’s only the layers after the first layer that sink in and I’m not sure why as the paint is not going on thin and I do not use solvent to thin my paint down. I’m also guessing that my surface cannot be absorbent as my first layer has an overall satin – semi gloss sheen which is normal. Any idea why this would happen?

I understand the reasons you suggest not oiling out as a final layer, but, if I use linseed oil only to oil out and then completely wipe off all excess so that I end up with a satin looking finish, am I not just replenishing the pigment with oil that should be there in the first place? If the oil replenishes the sunken in area and then gets completely wiped off leaving no excess oil, will that area really yellow if all im doing is putting something back that should be there in the first place? I’m asking this this as a final oiling out only on areas that have sunken in with the intention of not painting back over. Hope that question makes sense…any help will be appreciated…🙂 Thanks much!

Hi Chris –

On the question of colors becoming matte or sinking in after that first layer, would you say it is something that appears right away, after drying, or something that develops over time? Also, more with one color than another? Allover or more isolated to certain areas? Knowing a little more can help me in trying to troubleshoot. So, for example, we have seem some sinking in developing over time from the contraction of the oil after the initial oxidizing, where it will gain weight, and then begin to shrink as volatile material is released. Anyway, getting more info might help suggest a cause.

As for the issue of oiling out at the end, while it might always seem like you have wiped away any excess, if an area looks matte or sunken in then odds are it has a toothy surface and if you magnified it you might find that you really only got the oil that was up on top of the peaks but than additional oil might have flowed towards the valleys and be hard to get to – something I have tried to illustrate below:

This would be happening on a very small scale and not something you would readily see, so the danger is that very slowly, over a long period of time, these little micro-pockets of oil will yellow and something like an Ultramarine or Cobalt Blue can become slightly more gray or take on a slight greenish cast. And keep in mind that these are not simply our concerns but are truly coming straight from conservators that we work with who have seen this when attempting to restore or clean an older work. Presented with a situation like this, they really have no recourse or ability to fix it. This is also why they prefer artists using a removable varnish to equalize out any sheen issues, or fix any dead spots.

So those are at least the concerns and you will need to weigh the risks for yourself. And as always, if you have more questions, just ask!

Best –

Sarah

Hi Sarah

I have only just found your site. What a wonderful resource it is! Thank you so much for the opportunity to ask questions. Advice from someone with your expertise is much appreciated.

I have a some questions I would like to ask your advice on please:

I have been working on a cradled poplar panel that is prepared with a gesso surface. I notice the gesso is quite absorbent.

1) Can you please tell me which intermediary layer product I would be best to use on top of the gesso to lessen the absorbency before beginning my oil paintings please? The ,manufacturer of the board suggested oiling the board out – but I am not happy to do that.

2) I would like to talk with the manufacturer of the board to ask them which size (sealer) product they are using on top of the poplar board to ensure acid does not leach through to the painting? Can you please tell me what product you feel would be the most reliable please?

3) I have painted a portrait with pale pale caucasian skin colors. I used an alkyd medium with a touch of linseed to wipe over the face and neck, I am sure I wiped the excess off – but maybe not well enough? I then added my next layer of oil paint. I now find my subsequent layers are all very shiny and full of spots of sheen and some are matt – all close together and very spotty. She looks like she has measles. It is very well dried – about 6 months since my last layer. Maybe I need to repaint it with thicker paint to cover it? I have tried using thin layers of opaque oil paint but once dry, the spots come back. I cannot remove the spotty sheen with OMS. Will a final varnish fix it? Can you recommend a varnish brand? Ideally I would like to varnish the woman with a satin varnish and the background with a gloss varnish. More on this in my third question

3) I understand using different varnishes in one painting is called “spotting”. I hear this is sometimes done by conservators.

Are you able to give me any hints and tips on spotting varnishes please? Would it be possible to have a transition on the edges where the two varnishes meet? By this I mean could I create a 50/50 mix of the gloss with satin to enable a narrow but gentle blend (transition) between the gloss and satin separate layers?

Thank you again – so much for the wonderful work you do Sarah.

Hi Susan –

Thanks for the comments and warm appreciation – it means a lot to all of us, and to me personally. In terms of your questions I try to respond to them below:

1) We would suggest starting with a layer or two of our Fluid Matte Medium, which will help seal the surface and lessen absorbency while still providing enough tooth for excellent adhesion. If that is still too absorbent then we could discuss some other options – but start there as I think it will solve the problem.

2) GAC 100 is our standard recommendation for sizing panels under an acrylic gesso, especially when the plan is to paint in oils. Polymer Medium is another option, if for some reason GAC 100 was not available.

3) As you can imagine troubleshooting matte spots from a distance, especially without photos, is difficult. Spots can happen for a number of reasons and causes, from quirks in how some colors cure over time, to differences in the absorbency of underlying layers, or simply how thick or thin something is applied and how large the pigment particles are. One thing I would be curious about is if the matte spots appeared shortly after the paint had dried, or if it only slowly appeared after some weeks or months? As for what to do, you can certainly try repainting it but recreating a passage and matching color precisely is hard enough in the best of cases. Plus you would then need to wait for everything to fully dry again before vanishing. That said, if going that route, try adding some bodied oil – such as Stand – which should help the paint from sinking in. Otherwise you should be able to fix everything with a final varnish. In terms of brands, Golden makes a line of varnishes called MSA which are compatible with oils and which you can read about here:

http://www.goldenpaints.com/technicalinfo/technicalinfo_msavar

While you want to end up with the women in a Satin sheen, we would recommend first treating the sunken-in areas with some thin coats of MSA Gloss. While the tech sheet will recommend 3:1 Varnish to Solvent for brush applications, for this I would recommend going even thinner and trying a 2:1 or even 1:1 mix. The goal here is to slowly even out the sheen and keeping the varnish layer as thin as possible.

Once the mottled areas are fixed, let that dry for several days and then apply a thin coat over the rest of the women so that the entire area has a similar sheen. Let things dry ideally for 72 hours before applying the Satin Varnish, which should now go on more evenly.

4) While familiar with the concept we have unfortunately not done a lot of spotting here – at least in terms of truly creating smooth transitional areas and keeping a wet edge to facilitate blending on a larger scale. If nothing else we would recommend practicing this technique on other less valuable pieces or on some trial surfaces in order to get a feel for it. The varnish, especially when freshly applied, is easily resoluble by the next layer and so reactivating areas might be possible and brushing one varnish into the other should create something of a transition, but controlling the look and smoothness could definitely take some finesse and practice. So it might be easiest to settle on a single sheen for the piece overall while you explore and practice this more advanced form of varnishing.

That said. if still interested in pursuing this we would recommend posting this part of your question onto the site for MITRA – Materials Information and Technical Resources for Artists – which is run by conservators at the University of Delaware and they should be able to share any of their own tips or experiences in this area. You can find that here:

https://www.artcons.udel.edu/mitra

As always we hope this helps!

Sarah you are fabulous! Thank you so very much for this very detailed and well thought out reply. It is very much appreciated. It makes sense and you have explained the reasons for your suggestions which helps me to follow your reasoning and grow from there with the experience of actually doing it! I will practice first as you suggest. Thank you too for the suggestion and link of MITRA. I will look them up and if I have any problems – I will be in touch with them. Thank you so much again. Susan

Hi Sarah,

Thanks for this information! Reading the Q&A was especially helpful. My current work has large fields of dark colors and black. I like a smooth ground, fluid application, and ideally more matte surface to my paintings. I’m having trouble with sinking in, both in the thiner/earlier layers and in the more oily final coasts. I am using a mixture of walnut oil (for it’s resistance to yellowing and fluidity) and spike lavender (for a less toxic studio). The brush work is important and I hate having to repaint successful areas due to sinking in, especially because I have trouble with it in subsequent layers too.

Can you recommend a cold, tube black that resists the phenomenon best? I am currently using Mars Black. I prefer a tube black for consistency from piece to piece.

Could the “sinking in” in later layers actually be a type of beading up? If so, what can I do to fight beading up?

If I try a 50/50 mixture of stand oil and walnut oil in my medium to try and mitigate the sinking in without sacrificing all fluidity, I know the stand would increase the shine. Say I dissolve some wax medium into my spike lavender to reduce the gloss, so that my medium is stand, walnut, spike lavender, and wax. Could I use this medium to oil-out a painting? Or, could I use straight walnut oil to oil-out a painting done with this medium? Assuming the wax would create issues but interested to hear your thoughts.

I’ll check out MITRA too.

Thank you!

Aliza

Hi Aliza –

Sorry for the slight delay in responding – somehow your comment got filtered as spam. Which is far from the case – your questions are great ones and I will try to respond to as many as I can.

Can you recommend a cold, tube black that resists the phenomenon best? I am currently using Mars Black. I prefer a tube black for consistency from piece to piece.

– Ultramarine Blue and Burnt Umber (the Burnt Umber component might still make this prone to sinking in, but give it a try. Traditional recipe with a long history.)

– Phthalo Green or Phthalo Green Yellowish and Quinacridone Red or Quinacridone Magenta (should stay glossy)

– Sap Green and Egyptian Violet (Dioxazine Violet)

You will find other recipes with Prussian Blue, Indian yellow, and Quinacridone Red, allowing for more nuance than a two-color mix. I personally would avoid recipes that include Alizarin Crimson, but you could try substituting our Permanent Crimson into those instead.

I don’t think so. You would see beading up when trying to apply the paint. It would feel like a resist and pull back.

Stand oil is actually not all that glossy, in truth. More of a satin sheen at most. Worth a try just to see – perhaps on a test panel?

Oiling out is really meant as just applying some oil and then wiping off the excess before painting back into that area – rather than as a final adjustment to the sheen. In that sense, the wax would not be helpful, and I would just use Stand Oil and some solvent, or the Walnut Oil by itself, if needing to bring an area up for color matching and to continue work.

Yes – I think Walnut Oil by itself would be better than the recipe you gave with the wax.

Hope that helps – and MITRA is a great resource, so definitely check them out as well.

Hi Sarah,

I am a self taught budding artist. I have a problem I hope you can advise me on. I have been using mixed media boards and painting direct onto with oil, it begins to leave a greasy shadow to the same shape of the painting.

I also am painting direct onto canvas board and having a similar problem however less noticible.

I suspect the surface needs a thin paint layer to paint onto… I’m new to this and can seem to figure it out? Please could you help.

Hi Lee –

My first thought is that the boards are too absorbent, thus pulling out too much oil from the paint, or oddly could almost be the reverse, with the oil spreading out sideways because it is not being absorbed enough. In either case, and something we actually always recommend when painting on a preprimed surface, is to apply a coat or two of a high-quality acrylic gesso. This will help assure you that the paint has good adhesion and the ground have the right degree of tooth and absorbency. Plus it will provide some consistency even when you move from a canvas panel, say, to a multi-media board. The other possibility would be to apply an oil-based ground, such as the ones we have in our Williamsburg line http://www.williamsburgoils.com/grounds, or even a layer of a linseed-oil based white oil paint with no zinc in it. Our regular Williamsburg Titanium or Lead White meets those requirements, but if using another manufacturer’s paint make sure to check the label. Safflower-oil based paints, and ones containing zinc, would not be recommended for underpainting.

We hope that helps, but if you still have other questions about anything, from materials to applications, do not hesitate to reach out to us. If the question is not about a specific article, the best way is to email us at: [email protected] We can nearly always get a reply back out on the same day if it arrives in the morning, or the next day at most.

Dear Sarah, thank you for all the great info!

I had no choice but to oil out in full a painting after having had terrible problems with varnishing it. I removed the varnish with Gamsol. The painting was left comply sunken dried out and dull. I oiled it out with 50/50 Galkyd and Gamsol. It looks better but my very even and smooth black background is streaky.

Any idea how I can fix this problem? Would a second coat of oiling out help?

How long should I wait between oiling out coats ?

Thank you very much fir you time and expertise.

HI Sarah – I am new to painting, and currently, using water-based oil. A friend recommended that I oil out at the end. I used a Winsor-Newton medium. After reading your article, I see that I shouldn’t have done that. Is there any hope for this painting? If I wait 6 months to a year, will putting a coat of varnish over it, help at all? Thanks for your response.

Hi Mary – You are not alone in having oiled out a painting in that way – indeed, doing so has been and still is very common. While we do not recommend it, I would hesitate to say your painting was ruined – especially if you kept the coating very thin and wiped away any excess. In which case, hopefully, much of the oil was absorbed into the layer where any color changes will be minimal. As for the use of varnish, that is less about the prevention of yellowing than from scratches and dirt and potential fading of anything that might be fugitive. So I would say varnish if that is part of your normal process, otherwise, any yellowing is controlled more by light exposure than anything else.

Hope that helps!

Thank you so much, Sarah! This is all very helpful.

Warmly,

Aliza

Hi Sarah,

Thank you for all your comments and the original article. Your expertise is obviously in great need. My problem is that I finished a painting about 8 months ago, and decided to make a few changes to improve it recently. I used a liquid retouch varnish by Daler-Rowney over the painting, wiped it off and thinly repainted a few small areas completing the changes about a month ago. I made a couple more tiny changes with very thin paint two weeks ago. I tend to paint relatively thinly, without a medium so the painting has always needed a final varnish for the depth of color to come out. The areas where I used the retouch varnish and which I left alone have a nice sheen and are ever so slightly a tiny bit tacky, the areas which I repainted are clearly dull. The painting now seems to be touch dry. I feel I must use a spray varnish so that I do not disturb the new paint. My questions are: if I use a Krylon Conservation Retouch varnish spray, the only one I know of, in the next week, can I follow up 6 – 12 months with a final varnish? Or does it have to be removed? I have used Krylon Retouch Spray Varnish, and also Golden Archival Gloss Varnish before. I will have to purchase a new can of Krylon retouch varnish which is not a problem. However, I have a can of the Golden Archival Varnish on hand, although the can is probably a couple of years old. Instead of using a Retouch varnish, would it be safe and to spray several ( 3) very thin layers of Golden Varnish final varnish now, and follow it up with thicker layers of a final varnish later. The painting is due to go into a juried show soon. Thanks for any help you can give me. El

Hi Eleanor –

So glad the article was useful and always happy to help out!

Normally retouch varnishes should be able to be topcoated with a full strength varnish, and would normally say there should not be a problem IF staying within the same system. That “if” means that we are uncertain if our Archival or MSA Varnish is compatible with the Krylon and we have not done any testing along those lines. It very well might be – but that would need to be tested. If wanting to avoid that issue, you could either use one of Krylon’s other Conservation Varnishes to go on top of their retouch, or, as you suggest, you could try to apply very light layers of our Archival Varnish on top of your painting and then follow up with more layers later on. However, while we know other artists have done this, and we have limited testing that showed it could be okay, we do worry that the use of a UV protective varnish with a strong solvent on such a young film could cause problems, with the UV inhibitors possibly interfering with the further curing of the paint, and the solvent possibly biting into the young film and making the varnish and paint somewhat fused, making future removal difficult.

We wish we had a clearer answer for you but would rather be up front about the potential risks. Using a product formulated as a retouch varnish might in the end be the less risky, and while you wait for 6-12 months to pass, you could easily do some testing to see if the Archival Varnish can go on top. You would just need to create or find some piece you can use for testing to see if there are any obvious incompatibilities.

Hope that help.

Hi, first of all thanks for the deep research you posted on the matter. I have two questions for which I can’t find an answer yet. I would be very grateful if you look them up.

1. After priming the canvas I usually paint all of it with a single semi-diluted neutral layer of oil paint. That layer is not too thin as most people tend to do it, but also not as thick as paint straight from the tube. So what I’m wondering is – If I experience sinking on that first layer, is it a good idea to oil it out in order to prevent future sinking of successive paint layers?

2. How much does the number of coats of ground affects absorbency? You gave example for 2 and 4 coats of ground, but what if you use more? Does the surface become increasingly more absorbent as you apply more coats of ground?

Have a great day,

Daniel

Hi Daniel,

Sorry for the delay in responding – I was out of town until yesterday. Happy to answer your questions!

1) Oiling out is always fine IF – and that is the caveat – you are planning to paint back into that area. So, if you are prepping for a fresh session of painting and the area you will be working in has dead spots, oiling out is fine and can help. As too adding a small amount of bodied oil – such as Stand or Sun Thickened Oil – to the paint itself. But of course, that will change the feel of the paint, so does not work for everyone. We just would not recommend oiling out areas that you think might remain untouched.

2) This is a great question and while we have never tested this in a rigorous way, I feel that after -4 coats of Gesso you likely are plateauing out and additional coats will not add much. However, sanding – and especially wet sanding – can lessen the absorbency especially if the dust and slurry (in wet sanding) are not fully removed as these tend to clog up the surface and make it less porous. Plus the smoother a ground the less absorbent it will be simply because it has less texture and surface area, so the paint will tend to skate across the surface and feel more flowing.

Hope that helps!

Thank you for your answers, Sarah, they’ve sure helped me understand the oiling out process better. In the article, you’ve mentioned that some colours are more absorbent than others. That made me wonder which colours are some of the less absorbent? Anyway, if you’re too busy don’t feel inclined to answer this as well and of course thanks again for your answers.

Have a great day,

Daniel

Hi Daniel –

Not sure if I literally say some colors are more absorbent than others – at least I could not find that reference – but different pigments do have different oil absorption rates, so different paints will require different percentages of pigment to binder, but not sure that would be a practical guide to how absorbent any particular paint might be once dry. And in fact in the article we show where the pigment to binder ratio seems irrelevant – in the example of Phthalo Green and Raw Umber on polyester film – where particle size was clearly the bigger factor. That said, the pigments that are often notorious in terms of sinking in include the darker natural earths, like Raw and Burnt Umber, as well as most blacks.

Thank you for your response Sarah Sands. I’ll consider what you’ve told me.

Regards,

Daniel

Hi Sarah

Hope it’s not too late to revive an old thread. I’m just wondering what would be the most reasonable thing to do if I’ve already made the mistake of oiling out all over—in this case using a mixture of glair (distilled egg white) and Natural Pigments vacuum bodied oil (stand oil essentially, I suppose). I did this based on an oiling out recipe from a book that contains a lot of useful information but perhaps this bit was not so useful…Should I rough up the surface with some sandpaper and try to repaint over that, whereever I can ? Some parts don’t require repainting and I’d be reluctant to do any more in those areas for fear of ruining a good painting but could consider it if was absolutely necessary.

Hi Jenny –

Never too late! At this point, I would be inclined to just leave it as-is. A couple of things are in your favor – the use of glair and Stand Oil means this coating is already very low-yellowing, and then the fact that the layer was applied so thinly means that any yellowing will be extremely minimal if it is even something that you even notice at all. And trying to selectively repaint specific areas might just end up calling more attention to any changes than simply allowing the painting to age evenly. The one thing that could be helpful is to eventually varnish it with a UV protective removable varnish, like Golden’s MSA. as that will certainly remove a large amount of the UV responsible for yellowing and aging in general.

Hi Sarah…

any thoughts on the WN Painting Medium for oiling out in process?

I posted on the varnish page but included below also:I have looked at the reasons for the issues of sinking in.

I have looked over the technical docs. around vasrnishes and I have corrected my process to (hopefully) avoid the following problems in the future.

However I have a few older paintings that I need to “correct'” as the Gamvar varnish I have applied has been beading, uneven, spotty and dripping.

I want to try and carefully remove it or somehow even it out.

Here is the lowdown

I use a generous amount of chromatic black. My mixture is a combo of Aliz Crimson, Prussian Blue and Raw Umber.

Because of the dose of Raw umber, and the fact that I was using too much thinner, I consistantly had areas that “sunk in.”

As a result I was correcting this issue by oiling out using WN Artists’ Painting Medium as I painted to bring back the details and rejuvinate the work. Occassionally, I would apply this over the entire work when I was finished to create the most even appearance. Sometimes this worked well.

However, after letting the paintings dry for 6 months I tried to apply, (2 coats thus far), of Gamvar as a varnish and it failed to sink into the work and beaded and ofter dripped as mentioned.

My question: Is the non adherence and innefectiveness of the varnish a result of oiling out with the WN medium? Can I remove this with OMS or mineral spirits? and what is your opinion about the WN medium?

Hi Russ – Thanks for letting us know about your issues. Unfortunately we have never tested the WN Medium and in general – as you probably know from the article – we do not advocate oiling out unless painting back into those areas. But of course, your issues are more about what to do now with a painting where extensive oiling out has already occurred. Given that you are having the most immediate problems with the Gamvar, we would recommend reaching out to Gamblin to get their thoughts as they will know a lot more about this product than we do. In general beading-up speaks to a wetting issue, and that would likely be the result of the high oil content on the surface of the painting and the particular properties of the OMS that GamVar uses. With that in mind, you might try doing a small test in a section to see if wiping the surface of the painting with a full strength mineral spirit or turpentine prior to using Gamvar helps. We would also recommend posting your question on the MITRA site, which is staffed by helpful conservators that might have other suggestions:

https://www.artcons.udel.edu/mitra/

We wish we could help further but it is always hard to troubleshoot another manufacturer’s products as we simply do not have the familiarity of working with or testing them.

In the text for image 5 you say “These are both cast at 6 mil thick, about the same as two sheets of paper” which leaves me absolutely baffled. I have never met a 3mm thick piece of paper, one sheet of paper isn’t even 1mm thick by it’s self, by 3mm thick it would be heavy cardboard. So do I follow your millimetre number (which given the way you wrote it sounds like you aren’t that familiar with metric….) or go with the likeness to two sheets of paper?

A confused European

Hi Blissey –

The confusion comes about simply because “mil” feels and sounds like it must be referring to a metric unit but actually it is one of those odd measurements based on inches and stands for 1/1000 of an inch, or .0254 mm. I give the paper equivalence since even if someone is familiar with inches it is hard to imagine what 6/1000 of an inch looks like. We hope that helps. In the end, it is not so much your confusion as simply the crazy persistence of certain parts of the world not to adopt the metric system. 🙂

Hello Blissey.

Thank you for your questions.

Mil refers to 1/1000th of an inch, or .0001 . This is the standard unit of film thickness here in the U.S.

Regards,

– Mike Townsend

How can I describe a sense of relief and joy? I thought I was the only one with this problem 🙂

I am a beginner, I must be in my 10 painting and decided to change the traditional method I was working on which was acrylic plaster – primer with ocher yellow, white, tupernoid and damar varnish – underpainting with regular medium siena earth (20 parts of tupernoide for 2 damar varnish parts).

On 4 layers of acrylic plaster, I directly applied the underpainting with water-based oil paint, this created a very matte texture. After that I applied the traditional method of grisaille with a regular medium on a thin layer of flaxseed oil applied with the hands on the underpainting. What is my surprise 3 days later, the painting was totally dull, with some dead spots.

In another test I did painting on a layer of acrylic binder the result was dull but not full of dead spots.

My doubt, can I cover all of my current painting with acrylic binder and repaint it all? Or would it be better to reapply the whole grisaille in a thicker layer without medium? I do not know what to do

Thank you

Hello Vinicius,

Thank you for your comment. It might be worth experimenting with a new painting ground that is less absorbent, as many issues with dead spots can be attributed to highly absorbent ground preparations. 3 or more coats of Acrylic Gesso is usually sufficient to set up a nice ground for oil painting. If it is too absorbent, then a thin layer of Fluid Matte Medium or Matte Medium can be applied over top to lock up the surface. Oils can be painted directly on top after several days of dry time. Oil Grounds can also provide a lower absorbency surface for oil painting. Here is a video on applying Williamsburg Oil Ground: https://www.williamsburgoils.com/videos/how-to-apply-titanium-oil-ground

We do not recommend applying acrylic mediums over works made with oil paint. Acrylics are not compatible over oils, as the oil layers are water resistant and are too closed to provide good adhesion.

If the works are still in progress, then oiling out the areas you are going to repaint, can refresh the surface, make it easier to match color and blend edges. Oil out right before you begin work and paint directly into the wet areas. Try and keep the oil layer as thin as possible and only where you are going to work, as the oil will yellow with time and ideally, should not be left exposed. Also, adding a little oil or alkyd medium into your paint layers can increase gloss and keep the paint from going matte once it dries. Repainting or simply working over your grisaille after oiling out and with the addition of some medium in your paints should help. Keep in mind, higher additions of solvents into mediums can cause oil paint to dull.

If your paintings are complete and have dried for 6 months, then you might consider simply applying a varnish. Varnishes can unify the sheen to a satin or glossy surface and are removable layers that usually provide UV protection. GOLDEN MSA Varnish or Archival Varnish can be used on oil paintings. We do not recommend painting with oils over MSA or Archival Varnish.

We hope this helps. Please contact [email protected] or call 800-959-6543 with any additional questions.

Best Regards,

Greg Watson

I’ll be final-varnishing a painting mine with a combination gloss/matte. . .

Query, though: As in matte, wax the matting-agent, need that be

heated somewhat to assure that wax “fluid” beforehand?!

I do wanna get this right. . .

Hello Albert,

it is correct that varnishes with wax as matting agent, require gentle heating in a bain-marie or on a hot plate until the wax has molten into the solution. You can gently stirr the varnish while heatin to speed up the process. Feel free to reach out if you have more questions

Best,

Mirjam

Hi Vana – Before moving on to a reply I would like to ask about the “Walnut Stand Oil” you mentioned. This is something I have never come across and wonder if instead, it is a Walnut Alkyd Medium which I know is available. Please let us know if you can, as that can help in our assessment. In terms of your other questions, yes, varnishing should even things out, but you are obviously a bit pressed on the timing. On the good side, the paint was applied thinly, and if the walnut oil turns out to be an alkyd, that should help create a strong film more quickly. On the other hand, if a Stan Oil, those tend to dry very slowly and produce a much softer film. In an ideal world you would wait 6 months before varnishing, but alas, we unfortunately live in this one. So what to do, As you get into late Oct see if the film has become hard by using a fingernail and seeing if you can easily indent it. If it passes as fully dry, then it should be ok if you apply a light retouch varnish, which you can find ready-made by companies like Old Holland and Winsor Newton, although avoid anything that uses damar. The key is to apply it thinly and just to even out the sheen. If by some chance the paint is still soft then there is nothing I can see us recommending without fear of causing damage and I think you would need to try to work with the buyer to get them to understand. If it is October and that is not an option, then contact us and we will see if there is something else we might suggest. Or you could ask one of the conservators over at MITRA who are available to answer questions from artists: https://www.artcons.udel.edu/mitra/forums

As always hope that helps and let us know about the Walnut-based product.

Sarah

Hello Sarah,

I am so thankful to have come across your extremely inquisitive and knowledgeable article.

I am relatively new to oil painting and have been working on a commissioned piece that is almost entirely darker tones, as the composition includes a black and white poodle sitting upon a dark wood flooring – so a lot of black and burnt umber has been used. About 85% of the painting has sunken in so repainting these dead or sunken areas is not feasible. The commission was short notice, and they want it on the 23rd of June, but I was hoping to apply a final varnish 6-12 months from now. I have recently read that the final varnish would not completely fix this problem, however, so I am a bit stressed. I would love to hear your thoughts on this and any suggestions you might have. If a final varnish is a remedy to my issue, do you have any recommendations on the best product/brand to use?

Many thanks,

Lacey

Hello Lacey,

Thanks for your comments. It should be possible to significantly reduce the sunken in look of your darks with a varnish layer. Gamblin’s Gamvar might be a good product to try, as it can be applied about a month or so after a piece is completed as long as it is hard dry. It is a very thin, easy to apply varnish. They have good info on their website. Alternatively, you could apply thin glazes to the sunken areas with oil additions to some paint. this can be thinly applied to the dull areas, which should re-saturate the color. You can massage this layer into the surface to re-saturate and leave as thin a film as possible. these type of modifying glazes can unify the surface sheen and provide a saturated took to the image.

We hope this is helpful. Please let us know if you have additional questions.

Best wishes,

Greg

Wow so much information, could I ask your opinion on something (I think I know what your going to say, that they didn’t know as much back then as we do now)

I know a few historical famous artists that liked the matte look of an unvarnished painting, even noting on the back ‘DO NOT VARNISH’

Is this a thing? And if it’s valid wouldn’t that also mean they maybe oiled out / glazed as the final layer?

-also, does oiling out have a permanent lasting effect on appearance? Or does it go back to its original matte appearance once completely dried?

Last question – what are your opinions on spray varnish instead of liquid, and what shouldn’t you do if your using it

Thankyou so much