Oil painters concerned with fat over lean will often turn to information about the oil absorption values for particular pigments as a way to compare how oily or lean certain colors might be. However this has led to many misconceptions and outrightly wrong conclusions which seem to persist in various forums and articles. In what follows we try to correct this and show how using the actual ratio of the volume of pigment to oil, rather than the weight, gives a far more accurate picture and is usually what people have in mind when wondering about the amount of oil in any one particular color.

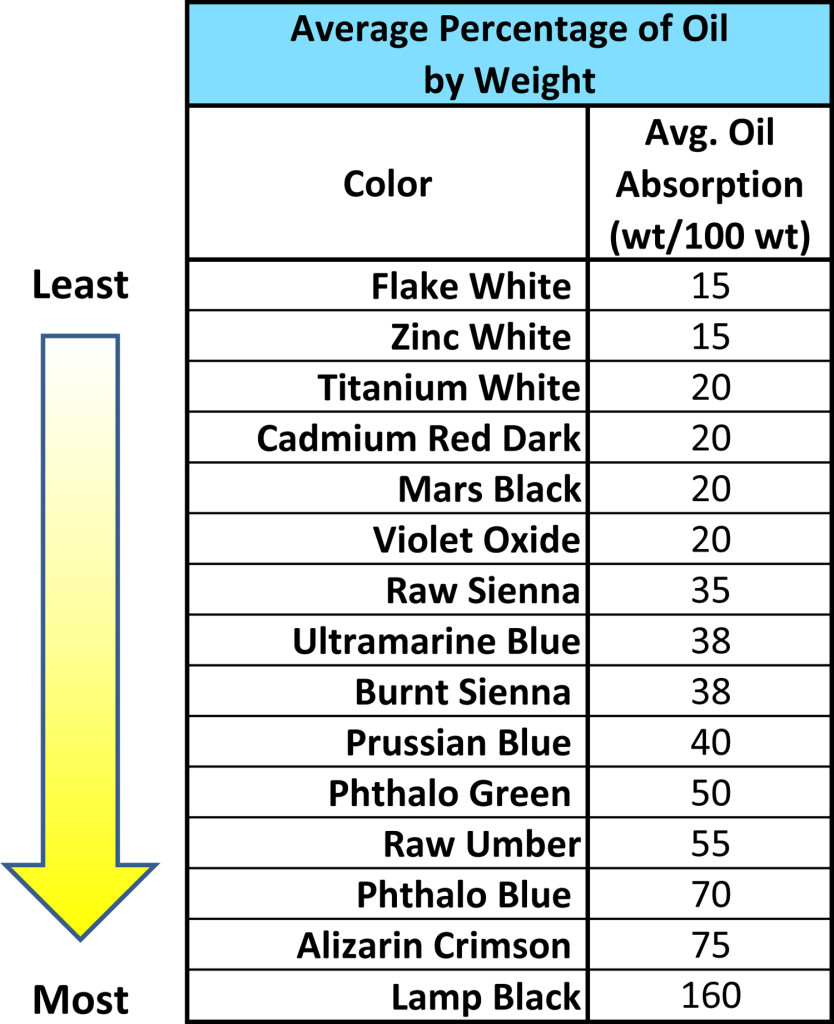

Oil absorption is defined as the ratio of the amount of oil by weight needed to form a stiff but spreadable paste from a known quantity of pigment, and is usually expressed as the number of grams of oil needed for 100 grams of pigment. This is extremely useful to know when making paint since measuring things out by weight is by far the most accurate. Unfortunately these figures can also vary quite a bit, depending on the reference you are using, so are usually expressed as falling within a range since the size and shape of the pigment can dramatically impact the amount of oil one needs. However, by supplementing the general average of what is found with our own calculations and tests using actual pigments, we have generated a table of 15 common colors with various percentages of oil (Table 1).

Some colors like Flake White are well known to require very little oil, while Lamp Black, at the other end of the scale, will actually require far more than even the pigment. But – and this is absolutely critical – all of these are based on the measurements of the weight of the oil to the weight of the pigment. The problem with this is that pigments like Flake and Zinc White are extremely dense and heavy, while ones like Alizarin Crimson, Phthalo Blue, and Lamp Black are incredibly light, and this has led to a false sense by many painters that Flake White, for example, is particularly lean, or that Alizarin has a very high oil content. And indeed this first table closely echoes the usual thoughts and listings of lean to fat paints.

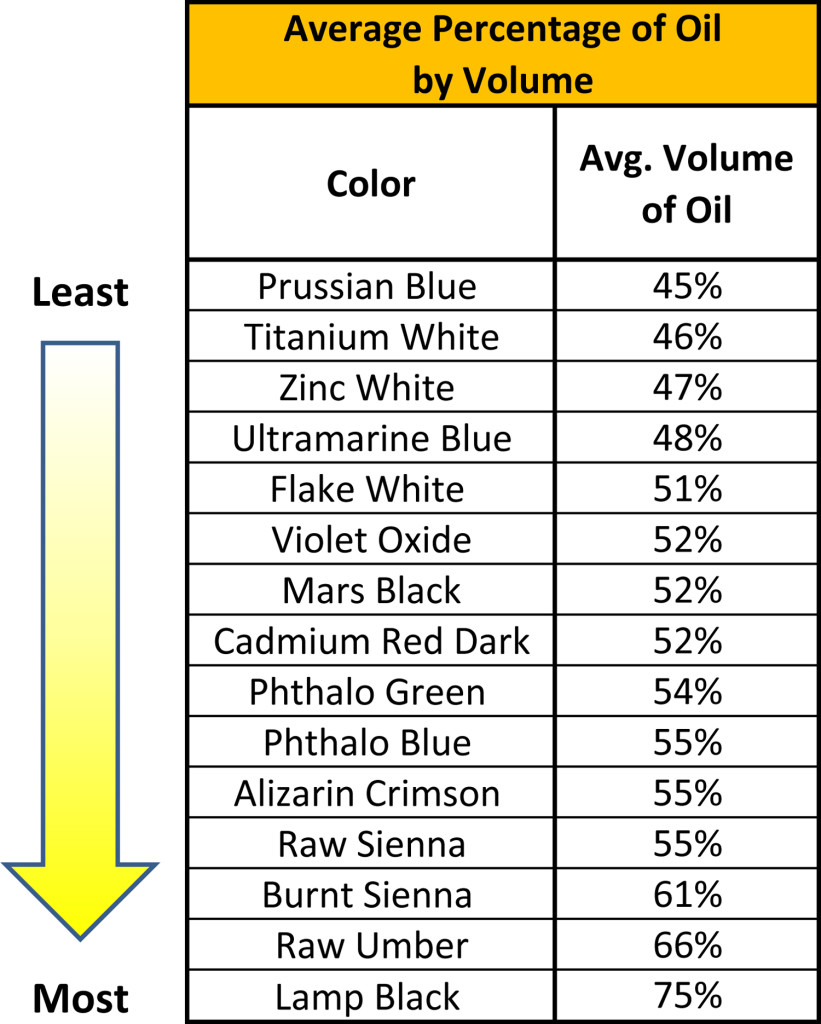

A more accurate way to think about this, however, is by volume instead of weight, because ultimately that is what most people are really interested in. Given a 37 ml tube of paint, how many mils of oil or pigment are inside? To calculate that one needs to know the Critical Pigment Volume Concentration, or CPVC, which like oil absorption represents the minimum amount of oil needed to make a set amount of pigment into a lean paint, with every pigment fully coated and all the spaces in between the pigment particles filled as well, leaving no voids. To calculate that, one is essentially using the density of the specific pigment and oil being used to convert from one system to the other, from weight to volume. The end result, though, is completely different and for most people, leads to a very unexpected reordering of the previous list (Table 2).

All of a sudden we can see that Prussian Blue and Titanium White, and even Ultramarine Blue for that matter, can actually end up having slightly less oil than Flake White, which is almost always seen as the ideal of a lean paint! Even Alizarin Crimson, often thought among the most oil heavy of colors, moves up ahead of such colors like Raw Umber or Burnt Sienna. Lamp Black, perhaps reassuringly, remains at the bottom, reminding us that some things at least never seem to change.

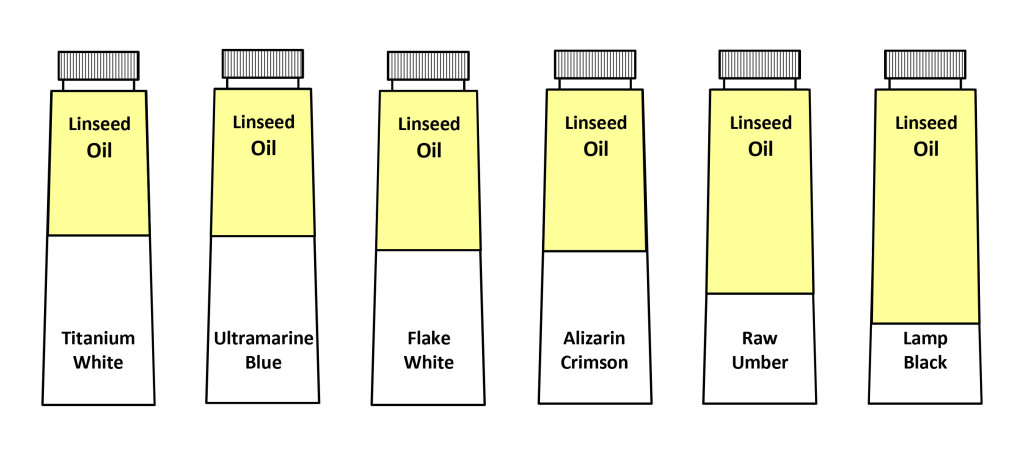

A more graphic way to represent this list is shown below, where we selected five of the most common colors and drew a line representing the respective percentages of oil and pigment by volume that one might find (Image 1):

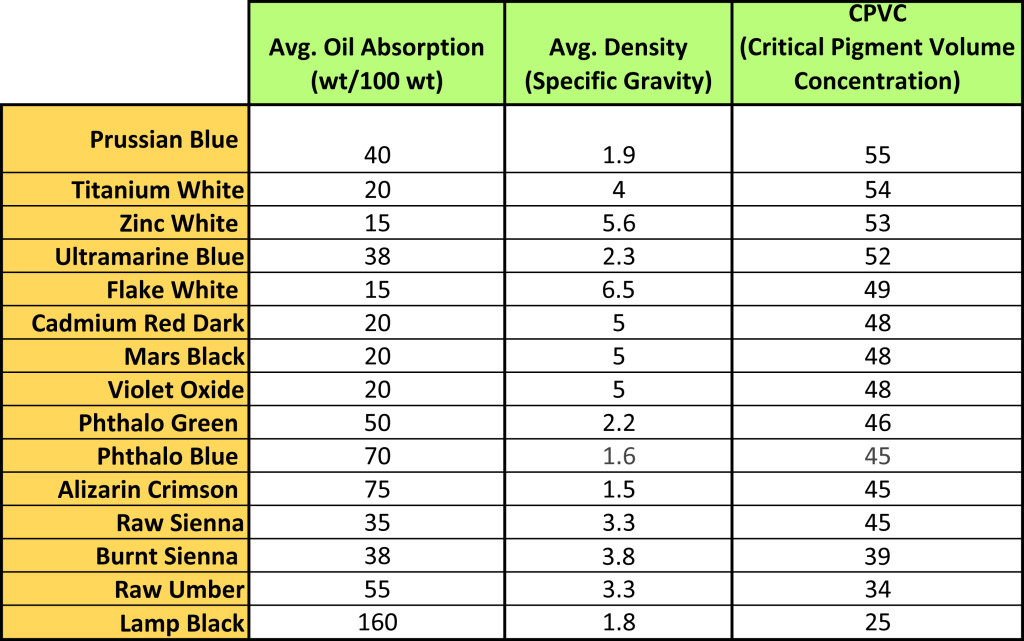

For those of you who like to geek out on these types of things, and we know you are out there, the formula for calculating the Critical Pigment Volume Concentration is the following:

CPVC = 1/1+[(OA)(p)/93.5]

OA = oil absorption value

p = Density (g/ml)

93.5 is the density of linseed oil X100. If different oil was used, this figure would need to be changed.

And here is the data for the colors that we chose:

As a final note it is important to remember that not every Burnt Sienna or Flake White will have the same oil absorption, and the use of any additives or fillers will almost always change the calculations. And of course, some paint manufacturers will hew close to the CPVC while others might opt for a slightly looser, softer feel, by increasing the binder level slightly. In other words, like all these types of tables, they are useful as tools to think about the properties of pigments but some wiggle room and leeway need to be granted when bringing this to bear in the real world of one’s studio.

Great article,

However, like most articles on several issues more questions are often raised.

When given a moment could you reference which instrument is used to measure the specific gravity?

Thanks Dean. And yes, almost every article will raise questions, especially shorter ones, so we welcome the opportunity to respond. In this case the Specific Gravity figures come from looking at spec sheets provided by different pigment manufacturers, as well as some reference sources, and while some range was common to find it was almost always within a very narrow range. The point of the tables was to be reasonably representative of what would be common to find, rather than claiming to be definitive, but certainly if using a specific pigment than you would want to plug its data into the equation. Lastly, just a note on measuring specific gravity – it is a fairly straight forward and well understood calculation, but is not something we carry out ourselves.

Dear Sarah,

Hope you are doing good..!

I have been working on the pigment dispersions and having issue while working on Red 112 and blue 15:0 as these two pigments become so thick that they can’t be grind on mill, can you please help in these, you can also connect on my whatsapp +9203200405624

Hi Umer – It is not completely clear from your question if you are making water or oil-based dispersions. If water-based, then it sounds like you simply need to be adding more wetting agent and water. If you do not have access to a universal dispersant for use in water-based systems, you might reach out to Kremer Pigments to see what they would recommend. If working with oils, then adding more oil should allow for the viscosity to become thinner. Oil paint is fairly simple in that way and while there are wetting agents that can be used in oil paints, it is not something we would recommend for an artists’ paint. Hope that helps.

can you tell me how calculate OA (absortion oil) in a mixture of 2 or more pigments?

for example if we have Tio2,Caco3,Talc

how i can calculate pvc,cpvc??

Hi Husein – Oil Absorption (OA) is actually very easy to calculate, although it will give you more of a range of values versus an objective, single number. Simply take 100 grams of the pigment – or, in your case, the blend – and add the oil you will be using one drop at a time until you achieve a very stiff putty-like paste using a spatula or palette knife. The goal here is not to have a paint-like consistency, but really just the minimum needed to wet out the pigment particles. Then simply calculate the grams of oil that was needed and that is your OA. To calculate the rest, you will need to know the calculated density of the pigment blend, which the supplier might be able to help you with. But depending on your goal, a lot of these types of calculations are not really needed to make a paint as ultimately you are still needing to adjust things until it has the feel that you like. The OA can certainly help tell you roughly what you will need just to initially wet out however much pigment you are using, and then from there, you would slowly add additional oil while milling the paint until it has the texture and flow that you want.

Hope that helps!

Thank you for this!

You are SO welcomed!

Thank you. I wonder with ever increasing powerful finer organic pigments, how will painters still have access to easy-to-use pigments. Phthalo might have been a wonderful and cheap invention for industrial painting, but for many painters these colors are way too strong. Put a phthalo opposite against a hansa yellow and you have a color with about 60 times as high tinting strength as hansa.

Now, added to that is the problem of high oil content, you end up with more and more transparent pigments.

I wonder what the future holds for painting, but I do home we eventually get safer alternatives to cadmium and cobalt, that are neither super powerful, nor super oily and transparent. But it seems like the art market is super small compared to the needs of the industry, so I don’t have very high hopes.

Thanks for the comment. You are right about the art market being very small and therefore not able to influence greatly the supply or development of pigments, while regulations and safety concerns will certainly continue to influence which ones remain viable. That said, we think most of the pigments artists currently depend on will remain for some time yet while new ones are constantly being developed and many of those, such as the Pyrroles or Bismuth Vanadate and Benzimadazole Yellows, hold great promise and new opportunities for expansion. So as always its a mixed bag and be assured we are keeping our eye on the ever changing landscape.

Enjoyed this. I have a bag of Prussian Blue bought last week, and I’ve not done artificial pigments before. I have a book somewhere also that gives me all the percentages of oil to pigment, but I have mislaid it!

Glad to have found this page to put against my mixture.

[I don’t know how to subscribe to this blog, so if possible…?]

Warren

Glad you found the article and enjoyed it! Will be interesting to see what you get as well. Keep in mind though, that Prussian Blue is one of those pigments where pure oil and pigment might not make the nicest paint as it can become very long, stringy, and with a strong bronzing tendency. But play around with it and see what you think.

As for subscribing, you can find a link at the top, just above the “J” in our header “Just Paint” O else just click on this link: http://www.goldenpaints.com/signup

Thanks!

Thankyou very much for this clear explanation Sarah. It seems mostly relevant to people mulling their own paints. It would be very useful to see a follow up article on what CPV considerations actually mean in painting practice for constructing an enduring paint film. Painters who are using high quality paint from the tube can assume the paint is usually already at its CPVC so we don’t need to concern ourselves about how oily a pigment’s CPVC is (as this is irrelevant to the old fat over lean rule)? We should either paint the whole thing alla prima all in one day or let earlier layers dry through before painting on top, but in reality we don’t necessarily paint that way

eg Umber (oily) is fast drying but brittle. If we lay down an imprimatura or make a sketch with earth pigments, is OK to paint over it with a slower drying pigment before the earth has dried?

What if I put on fresh paint straight from the tube (mixes of different pigments) nearly every day day after day for a week or a month? Does the fat over lean rule still apply after all?

What if I want to scumble a faster drying pigment over a slower and more brittle one? Use a slower drying medium in it?

Alkyds could help in some of these situations but I avoid using them (poor ventilation). Many thanks if you do address these questions.

Hi Jay –

These are all great questions although unfortunately few have hard, fast, scientifically proven answers. We do think you are right in assuming that the concept of CPVC can in many ways replace the earlier “fat over lean” rule, at least in terms of paints as they come from the tube. Far more relevant at that level, it seems, is keeping track of slow over faster drying colors, and thicker over thinner applications. “Fat over lean” would be more applicable when considering the addition of mediums or the use of solvents when constructing a painting. Otherwise you are generally safe when approaching a painting as largely alla prima, or allowing each layer to fully dry prior to the next. But saying that those are the two safer poles, shall we say, along a continuum of approaches, should not mean one cannot occupy any of the middle ground. Certainly many paintings that we admire and continue to appear in good shape were worked on daily, while others that must have seemed like the model of a slower, indirect, more academic approach might now display surface cracks. And of course, nearly all those appearances of cracks or other surface problems only appear decades after the fact and it is hard to untangle all the variables to know what is ultimately at fault – with fluctuations in the environment being easily as detrimental as anything in terms of techniques. Also, even the thought of some pigments being more flexible or brittle than others is highly dependent on the total painting as we know now from various studies that lead ions, for example, will migrate from a lead ground and travel throughout the various layers, lending a greater flexibility and durability to the painting as a whole.

So, as you might quickly see, it would be hard to give cut and dried answers to each case. In general we can state these things with some degree of surety:

– painting on an inflexible support, or mounting canvas to a solid panel, is by far the single best thing one can do to limit risks to a painting.

– use the minimum of solvent and oils whenever possible At the same time, when they are needed they are needed – just keep things as moderate as you can.

– use linseed-based paints as much as possible, as linseed will produce the most flexible and durable paint films.

– limit the use of zinc white or blends that use zinc oxide in their mix. Especially avoid zinc-rich paints in underlying layers or grounds, since zinc forms very brittle films.

– use lead white whenever possible as it is by far the most flexible option for a white and will contribute to the flexibility of the painting as a whole.

– if using an oil ground, consider a lead ground as again it is the most flexible option and will contribute, through the migration of lead ions, to the flexibility of the painting as a whole.

– avoid extremely thick paint applications

– exhibit and store a painting in as stable an environment as possible

– keep one’s technique as simple as possible.

As always hope that helps and if there is anything else we can do, just ask!

Hi Sarah,

Thanks for the post. I fear the information here might be a little incomplete.

In particular, zinc and other pigments are known to participate in chemical reactions that lead to the formulation of soap compounds. These can be a huge problem in paintings, as they can agglomerate and push through subsequent paint layers. In particular, zinc is known for causing problems with soap formation and delamination. It is a stable and useful pigment in acrylic, but in oil it is highly reactive.

https://phys.org/news/2017-04-video-weird-chemistry-threatening-masterpiece.html

Hi James –

The focus of this article didn’t really allow for a digression into those types of issues as we wanted to just look at the issue of differences in pigment/oil ratios when switching from weight to volume.

You are quite correct about the issues with metallic soaps, with both lead and zinc being problematic; lead soaps because they become mobile and can cause nodules to erupt through the surface, while zinc soaps generally accumulate at the interfacial boundary between layers and are linked to delamination, cracking, and embrittlement. And of course, the issues with lead soaps are usually in a time span counted in centuries, while zinc issues begin to appear in a matter of decades or years. Anyway, it is certainly an area we have followed closely and remain in touch with many of the main researchers doing this research. Ultimately it deserves an article on its own.

Thanks again and if you have any other concerns or questions just let me know.

Hi,how can I make lighter paint?

I want my each paint volume to have nearly same wight,is it possible?!

Hi Sina – There is no easy way to make all the colors weigh the same since the weight of each color is mostly determined by the pigment’s density. The only thing we can think of would be mixing our Extender Medium

http://www.williamsburgoils.com/mediums

with each color – say at a ratio of 1:1. Doing that would effectively make the colors much closer in weight without changing the mass tone too much. However the colors will also have far less tint strength and not be as bright or saturated.

Is there a reason why having all the colors weigh the same is something useful for you? Perhaps if we understood your needs better we could make a better suggestion.

As always hope that helps and if there is anything else we can do, just ask!

Thank you so much

Actualy,I’ve started to make paint tubes

And I am using aluminum hydroxide for extending and stablizing the oil paints

But Titanium dioxide pigment becomes too heavy,and stringy (nearly for all synthetic pigments) no mater how much I grind it(by 3 roller mill).

I was thinking to sell them in future,so its better to be in same volume and weight.

I think I need a filler which absorb more oil,according to your article.And I dont know what it is.

I have limited sources where I live, your article and guides are so useful,thanks

Hi Sina –

As you obviously recognize, depending on the pigment you are using making oil paint is not always that easy and it requires a lot of time and testing to create a stable formula that produces a paint with a nice feel. While we cannot provide you with our recipe for Titanium White, and we do not use aluminum hydroxide, you might try playing with the addition of barium sulfate (blanc fixe) or calcium carbonate as a way to moderate the feel and texture of the paint. We wish you the best of luck in your explorations.

Hi, thank you for this article. I noticed you mentioned in an earlier response that CPVC could replace the old fat over lean rule. I don’t quite understand this. Wouldn’t a paint film of say, Raw Umber, with a high amount of oil to pigment ratio, make a less absorbent film for future layers of paint to adhere to, especially if those later layers have lower oil content? I have seen low oil content colors have a hard time adhering to high oil content colors, no medium added to either layer. I was under the impression fat over lean is not only flexible over less flexible, slow drying over fast, thick over thin, which seem to be more long term concerns, but also fine/slick over coarse/absorbent. These qualities don’t necessarily need an added medium to exist in a paint layer. This makes certain fat but fast drying colors particularly worrisome (umbers and siennas). But regardless of whether you are adding medium to the paint or using it straight from the tube, don’t you want to follow the fat over lean rule, meaning CPVC should just follow that rule and not replace it?

Hi Steve –

Thanks for your response and questions. The value of using CPVC as a concept, in place of Fat Over Lean, is that one would then consider any well made paint as essentially ‘lean’ when squeezed out of a tube since it has the optimal pigment to binder ratio using the minimum of oil needed to coat the particles and fill any voids in between them. As a paint film, even when moving from one pigment to another, each with a different oil absorption ratio, you are always at a maximum packing of solids in a paint layer. At that point, the properties we think are truly the more important ones to keep track of – such as flexibility, drytime, smoothness, sheen, etc. – have more to do with pigment properties and particle size than a strict measure of how much oil was needed to make the paint initially. One needs look no further than the many conundrums and exceptions the article point to – such a lead white, which is exceptionally flexible and certainly desirable in an underpainting – not being leaner than many colors we think of as slow drying and problematic.

that said, you are right that glossy slick films make adhesion of additional layers difficult, but with straight paint this is rarely if ever a function of oil percentages alone and more dictated, if anything, by particle size. A case in point: Raw Umber requires more oil that Phthalo Blue, but clearly dries to a matte and toothy surface that is fine as an underlying layer, while Phthalo dries to a glossy surface, regardless of being ‘leaner’. The difference here is solely how large or small the pigment particles are in the two different colors.

Finally you might be interested in a similar discussion that took place on MITRA (Materials Information and Technical Resources for Artists), the website run by the conservation department at the University of Delaware, which you can find here:

https://www.artcons.udel.edu/mitra/forums/question?QID=136

And look for a fuller article on this concept in an upcoming issue of Just Paint – so check back soon!

Thanks, Sarah! That was my question! I will respond on there as well, but thank you for that very clear explanation. That makes a lot of sense and clears up what I was confused about. This was a great article and I will definitely check back soon.

Hello, thanks for,the article. I guess this is just for oil paint ??? Or is density same for acrylic paints ?

Any chart on that ? Would really be helpful . Thx

Hi Peter – In this specific instance the article is really only applicable to oil paints, but the good news is that we just published an article (Pigment Volume Concentration and its Role in Color)that took this same issue and looked at it in terms of various binders, including acrylics, and you might find that interesting to read through. You can find that article here:

https://justpaint.org/pigment-volume-concentration-and-its-role-in-color/

Essentially as you move out from oil paints you would substitute the oil absorption concept for Critical Pigment Volume Concentration, but the concept remains the same. Hope that helps but if you still have questions after reading through all that let us know!

Thanks for this article. I have been doing a research about oil absorption of pigments and extenders and getting confuse about which oil to use. I have known that Linseed oil and Paraffin oil, n_Dibutyl Phthalate are being used to determine the oil absorption but I have no idea which one for variety pigments and extenders. Can you help me to get some more information about this? Thank you very much!

Hi Ha –

Thanks for the question. In both of the ASTM Standards that cover calculating Oil Absorption for Pigments (D1483 and D281) the oil that is required is linseed and that is what we would recommend using. We hope this helps but if you have more questions simply let us know.

Dear Sarah Sands,

What would be an appropriate percentage, volume to volume, of beeswax to have in the final paint so that you get the desired buttery consistency in the paint but at the same time achieve longevity (no cracking, peeling, delamination, blistering etc.) for the paint film once it has dried. And how would this effect the CPVCs?

Hi Michael –

In general, you want to use as small a percentage of wax as you can and should be adding it mostly as a way to improve the stability of the paint. In the process, it will impact the feel some and can help shorten some pigments that produce long and ropey paint, but we would hesitate to rely on it to impart a lot of body. The more wax you add the more susceptible to solvents and the softer the paint film. So, with all that as a given, our general guidelines would be to keep beeswax to a 1-3% addition by weight, with perhaps 5% as an upper maximum. Translating that into a volume measurement is not so easy as of course weights of different pigments can change dramatically. But what you might look at doing is to heat the beeswax into your linseed oil, and since they are very close to the same density – 8.02 lb/gal for beeswax, 7.89 lb/gal for linseed – you could aim for, say, 4% of the volume of your oil. As oil will never make up 100% of your paint, and oil content by volume runs between 50-70% for most colors, your wax would likely run between 2-3%. And of course, you could always adjust the ratio of wax to oil up or down. As for how it will impact the CPVC, the wax would be included with the solids. Essentially the wax would be taking the place of some of the pigment. As CPVC is more a theoretical, idealized concept, and it all comes down to what percentage of oil makes a stiff paste, we would not get too caught up in trying to calculate the impact. At the percentages being used, we doubt you will notice it much – which is actually as it should be!

Hope that helps.

Please suggest the best pigment binder ratios for all the regular pigments and extenders during grinding.

Thanks for the comment. While that might seem helpful the truth the ratios can vary widely based on pigment source, particle size, type of oil, etc. So even the ratios we give in the article are based on our own information but might not be appropriate or match the pigment you use. For example, in Ralph Mayer’s The Artist’s Handbook, 5th Edition or later, there is an extensive section on pigments that lists the Oil Absorption for each. But you will quickly see why this has little practical value for the paintmaker. Phthalo Blue (PB 15) has a listed Oil Absorption range of 32-70 parts per 100 of oil, natural red oxide (PR102) 6-21, diarylide yellow (PY83) 39-98, etc. Unfortuantely, to get something that is truly useful, you will need to calculate your own values using the specific pigment you are using. Doing this is relatively simple – weigh out 100 grams of pigment then add linseed oil very carefully, weighing exactly the amount used to eventually form a stiff but workable paste with a palette knife. That will be your general oil absorption level, which can be used as a rough starting point when making your own paints, adjusting up or down from there as needed.

Hope that helps!

woooow i love this article it really help me on my project on oil paint production and analysis

So glad it was helpful!

Dear Sarah Sands,

Thanks for the great article it has helped me so much. I have a few concerns regarding particle size. Won’t particle size affect the amount of oil needed and therefore the numbers in the table you provide? If so, were these pigment particles all of the same size or bought from the same company or is the difference in size not going to change much/anything to the outcome of the table?

Thank you

Hi Geronimo –

Particle size will absolutely impact oil absorption ratios, so the tables we showed should only be taken as one set of fairly typical examples, but certainly your own source for one of those pigments could need more or less oil depending on particle size and even how you make the paint. For example, machine milling disperses pigments more effectively than hand mulling, so will also use less oil in the process. Particle size differences are also one of the main reasons you will find oil absorption figures reported as a range in most references rather than a set number.

The pigments we used did not all have the same size, as each type will have their own intrinsic particle size ranges. Bruce McEvoy’s Handprint website has a useful table showing the broad, rough differences between the various ones:

https://www.handprint.com/HP/WCL/pigmt3.html#particlesize

Also, even when you buy a single pigment, the reported particle size is really just a median average taken from a wider range. And finally, some pigments will vary in particle size over time as pigment manufacturers change their processes or opt to produce smaller particle sizes to get higher tint strengths, for example.

Ultimately, the tables we showed can be instructive and provide a broad sense of differences, but the moment you truly get involved with paintmaking, where different oils and additives and milling processes all have impacts, not to mention all the variations in pigments already mentioned, and you start to see how complex all of this can become.

Hope that helps and if you have any other questions, just let us know.

Dear Sarah Sands,

Thank you so much for your answer. I am at school in my last year before university (I say that because I don’t know if you would call it college or school or another word) and I have to write a thesis type document of around 30 pages on a subject. I chose to talk about the science behind the materials involved in paintings. I have an approximately two page part that talks about PVC and pigments (I also talk later about degradation and scientific methods of analysing artworks later and I also did an internship to learn and be able to talk about restoration which is why this part seems so short). Since it involves so many different things, like you said, and since I had no prior knowledge in this area whatsoever, I am struggling to know if what I have written is completely wrong or ok.

I don’t know who could possibly help me check it apart from you but all I would need would be for someone to read it and just tell me where I say something that is misguided, overly simplistic or just plain wrong. If you didn’t want to read it, which I would completely understand, do you know who else I could seek help from? What do I need to search to find people with knowledge similar to yours?

If you want I can send it to you either by email or here in the comments (or any other way you can imagine) before you decide whether to help me.

Thank you so much for reading my comments,

Best regards and have a great day!

Geronimo.

Hi Geronimo –

Thanks for the follow-up. I will email you directly regarding the paper.

Hi

In my country the good quality of oil brands is too expensive.I am not satisfy with studio oil colors wich is cheaper. Do you believe grinding pigments (even not first quality) is better than studio oils that are on the market?

Thanks

Hi – That is a hard question to answer. We believe there is a lot to learn by grinding one’s own paints, but we also think it can take a lot of time and trial and error to get the paint to be stable in storage and have the feel you want. Technically the three roll mills used by most manufacturers will disperse the pigments more efficiently, with less oil, and thus produce a paint that is leaner and more even in texture. On the other hand, very cheap paints can contain a lot of additives that compromise the quality and complicate the long-term durability of the paints once they dry. Lastly, when making your own paint, while some pigments can be done using just the pigment and oil, a lot of them will need additives such as driers, wax, barium sulfate or precipitated calcium carbonate, as a way to get better stability and performance. So it truly becomes a craft that would take time to learn and master.

We wish there was an easier answer. Certainly if you are curious and interested, we would say start small with a couple of easy pigments, like an iron oxide, cadmium or cobalt. If nothing else you will learn a lot in the process and start to discover the properties you like. As you probably know, if you search online there are any number of sites that will provide instructions for making your own oil paints. This one, from my own searches, seemed particularly good and includes some proper safety guidelines as well:

https://www.instructables.com/id/How-to-Make-Oil-Paint/

And of course, reference books like Ralph’s Mayer’s The Artists Handbook has a ton of useful if sometimes dated information.

Hope that helps and let us know if you have any questions.

I cant thank you enough for your great information about oil absorption of pigment .kindly i have some question

Firstly why the standard oil in this test is linseed oil ?

Secondly if i have more than one pigment differ in density in my paint formulation how can i calculate cpcv for my paint ?

Regards

Ahmed salim

Hi Ahmed –

While it is true that oil absorption is usually calculated with linseed oil, that is simply an industry standard as linseed oil paints were the norm for so long. But you could certainly do the calculations based on other oils. So, if you were working with safflower or walnut oils in your formulation then it could make sense to use those for the oil absorption calculations.

As for having multiple pigments, you could work out the oil absorption for each pigment separately and then calculate the combined cpvc from the ratio of the two pigments in the recipe using this:

CPVC = 1/1+[(OA pigment 1 x % of pigment 1 in formula + OA pigment 2 x % of pigment 2 in formula)(p of pigment 1 x % of pigment in formula + p of pigment 2 x % of pigment 2 in formula)/Density of oil]

or more compact

CPVC = 1/1+[(OAp1 x %p1 + OAp2 x %p2)(pp1 x %p1 + pp2 x %p2)/Density of oil]

OA = oil absorption value

p = Density (g/ml)

However: While the above might give a rough calculation, the moment you mix two or more pigments things get much more complicated than a simple formula can reflect since the optimal packing of the pigments together is not the same as the ratio of the maximum packing for each of the pigments separately. Think of the contrast between pebbles and sand separately and then blended together, where the sand will now occupy the spaces between the pebbles. Ultimately CPVC is really best figured out by feel and hand more than anything else unless trying to calculate an idealized theoretical model. Many modern paint formulas might contain several pigments, a couple of inert fillers, and a stabilizer like wax, and those ratios will be constantly changing to compensate for variations in the raw materials. So you can imagine the nightmare of trying to constantly calculate CPVC in that type of situation. On a more practical level, what you want to go for is simply paying attention to how much oil you need to add to get a paste that is just spreadable with a palette knife. That will define roughly the CPVC, and then most manufacturers will go a touch above that to allow the paint to flow a little more easily as the CPVC paste might be quite stiff and unpleasant for many painters without some added medium.

Hope that helps.

Interesting. Are these oils and crude oil related ? How is paint price affected with the price of crude ?

Hi Kal,

No, not at all. The oils used in fine art oil paints and mediums are derived from plant/vegetable sources.

Thanks,

Greg

Hi

Do pigments with lower volumes have lower absorption?

Hello Faeze,

Thank you for asking. The tendency is that pigments with higher densities have lower average oil absorption rates.

Hello,

I have a question regarding the calculation of the CPVC for pigments to be used in encaustic paint. Is the OA (oil absorption) value of the pigments still valid in this case?

If I wanted, for example, to calculate the CPVC of ultramarine blue in wax, would I still use the OA value of the pigment? Would the calculation look like this?:

1/1+[(38×2.35)/0.95)]

Being 38 the OA of ultramarine blue; 2.35 the density of ultramarine blue and 0.95 the density of Cosmoloid H80

Thank you!

Hello Catarina,

Every binder has a different loading potential. So, while determining oil absorption would offer some information about the binder demand of a pigment, it would only offer comparative information to previously known pigments in your wax system. Unfortunately, oil absorption would not allow for CPVC calculation in encaustic.

We hope this is helpful!

Barium Sulphate mentioned as stablizer in paint formulations, does it also reduce the high chroma of Phthalo colors and help make it more opaque. If not how does one increase the Opacity of colors, since most newer pigments are too transparent?

Hi MPC –

Barium sulfate on its own makes a semi-translucent, greyish off-white oil color which, when mixed with more transparent organics like Phthalo Blue, would increase opacity and lower chroma, just as you suggest, and in darker organics would also raise the value making it appear like a tint. You get a very good sense of the impact in the following article, where we show a picture of our Extender Medium, which is a blend of Barium Sulfate and Calcium Carbonate, mixed into a Phthalo Turquoise (a blend of Phthalo Blue and Green) and Ultramarine Pink right near the end:

https://justpaint.org/williamsburg-alkyd-resin-and-extender-medium/

While the Extender Medium includes calcium carbonate, barium sulfate on its own would be similar.

Hope that helps.

Sarah

Thank you so much for posting this! I’m mixing my own interference, fluorescent and phosphorescent (“glow in the dark”) pigments into oil paint these days. Do you have any information on the volume ratios or absorbency of those kinds of pigments?

Could I ask you to please speak as you can to the relative absorbency of different types of oils (which I understand have different dry times and propensities to yellow – in the above I am using walnut oil because I want a non-yellowing oil that will dry slowly).

Finally, could I please ask you whether you have a preference for either Barium Sulphate or Alumina Hydrate as an extender? I should mention that I am using neither in the above efforts, as they only dim the interference/fluorescent etc effects; please treat this as a separate question.

Thank you very much for your time!!

Takashi Hilferink

Hi Takashi –

I think the biggest lesson in our studies is that these calculations are better arrived at empirically as even with just pigment and oil, the variables in pigment particle size and properties of the oil, and even the temperature and humidity where you are, will impact the results. Oil absorption is really simply derived by adding oil drop-wise to a known volume of pigment until you get a workable paste. At which point it still might not be at the viscosity you desire – so invariably one tends to be slightly above the critical pigment concentration to allow for some flow. Also, for interference pigments, keep in mind that you really cannot mill these as they are fragile, and will fragment under pressure, so we tend to simply stir them into the oil until we get a workable viscosity. Also, they are formed on flat platelets of mica which are very nonreactive and relatively smooth compared to the craggy surfaces of most pigment particles, so will have little oil absorption.

On the different values for oil absorbency based on the types of oil, there certainly will be some variability but not sure how significant it would be, and I have not specifically looked at quantifying it. If I find some information for you, however, I will report back. But again, I think the differences will be subtle. Can you say what your concerns are? It might be that other factors – like feel, yellowing, durability – are more important for the choice of which oil to use than something like oil absorption.

Finally, we do not use aluminum hydroxide in our paints, although it does form the base for some pigments, such as alizarin crimson. Both will extend paints, but barium sulfate will be more opaque and heavier, while aluminum hydroxide will be lighter, fluffier, and more transparent, thus when used in high amounts can show the yellowing effect of the oil more. But used in small amounts should be fine. I think the choice will be more on the feel and opacity you are after.

Hope that helps!

Very good information here. Have you done research on the pigment volume concentration for any additional pigments? Specifically Cadmiums, Cobalts, & Quinacridones…….? Its not info that seems to be readily available.

Hi Cory –

Happy you found the article helpful, but no, we haven’t done these types of calculations with other pigments. The ‘research’ for the most part is simply plugging in numbers either calculated from an actual pigment or looked up on spec sheets or via Google searches and plugging those into the equation. But as I mention at one point in the comments, while we felt this article was useful to give people insight into what all these terms and concepts mean, and to dispel the huge misconception that Lead White is particularly lean, none of this is really needed to make your own paint. Essentially CPVC is built into any well-dispersed workable paste that uses just oil and pigment. But how much this will help anyone trying to understand manufactured paints out in the world is somewhat dubious since every brand will be different – due to the use of additives and modifiers, which will change the calculations and the fact that pigment density and oil absorption will change from pigment supplier to pigment supplier, and even a single pigment’s oil absorption can fluctuate from batch to batch. Even for us, using this formula at best gets one ‘into the ballpark’, so to speak, when optimizing a formula or working with a new pigment, but ultimately the art of paintmaking takes over and it’s all in the feel.

Hope that helps!

Hello!

Thanks very much for this article. It explains many mysteries while, of course, suggesting many more! Although it seems like determining the OA is somewhat subjective, I see that there is an ASTM standard for how to do it. Is there a reference work that has OA and density values (or perhaps the CPVC itself) for common pigments? It would be very useful to be able to look such things up since I often want to adjust ratios of pigments relative to each other and this would provide a rational way to approach this when using manufactured paints.

Another question is just about the formula, which says that the density of linseed oil is 93.5. That can’t be right, though, because if that’s g/ml it would mean that linseed oil weighs 93.5 times as much as water, which clearly isn’t the case. Maybe 93.5 is 100 times the density?

Thanks for your blog sharing pigment oil.