In blog posts and workshops the warnings can seem dire: add too much water, we are told, and the acrylic binder will break down, causing paint to flake off or adhesion to fail. Some will set the magical mark at 30%, others at 50, but almost universally the rules are presented without citing or showing any evidence. So we thought we would fill in some of those blanks and share what our testing reveals.

Water is clearly a central ingredient of artists’ acrylics, which even at the start will usually contain somewhere between 45-55% water. So it can feel natural to be hesitant before adding a lot more. Surely there must be a breaking point, but where? For years our standard advice was that a 1:1 ratio was very safe for most of our paints and mediums; plus, it had the advantage of being easy to remember while greatly erring on the side of caution. However, our current testing shows you can go a lot further than that before encountering significant issues. Just how far? We think you will be surprised.

Core Findings

- Adhesion: We saw no adhesion failure of any of our paints, no matter how thinned down with water, when applied on top of acrylic gesso.

- Sensitivity to water and other acrylic products: Colors we tested that are typical of our line, like Yellow Oxide and Phthalo Blue Green Shade, showed no sensitivity to water or various acrylic products even when thinned with 20 parts water. In fact, sensitivity was mostly limited to worst-case scenarios of highly thinned down mixtures (1:20 and 1:100) involving pigments like Raw Umber, which has a high clay content, or the more dye-like Anthraquinone Blue.

- A safe way to thin any ratio of paint to water: By using a minimum blend of 1 part acrylic medium to 10 parts water, we essentially eliminated sensitivity to water or other acrylics, even with highly sensitive pigments thinned at a 1:100 ratio.

The Tests

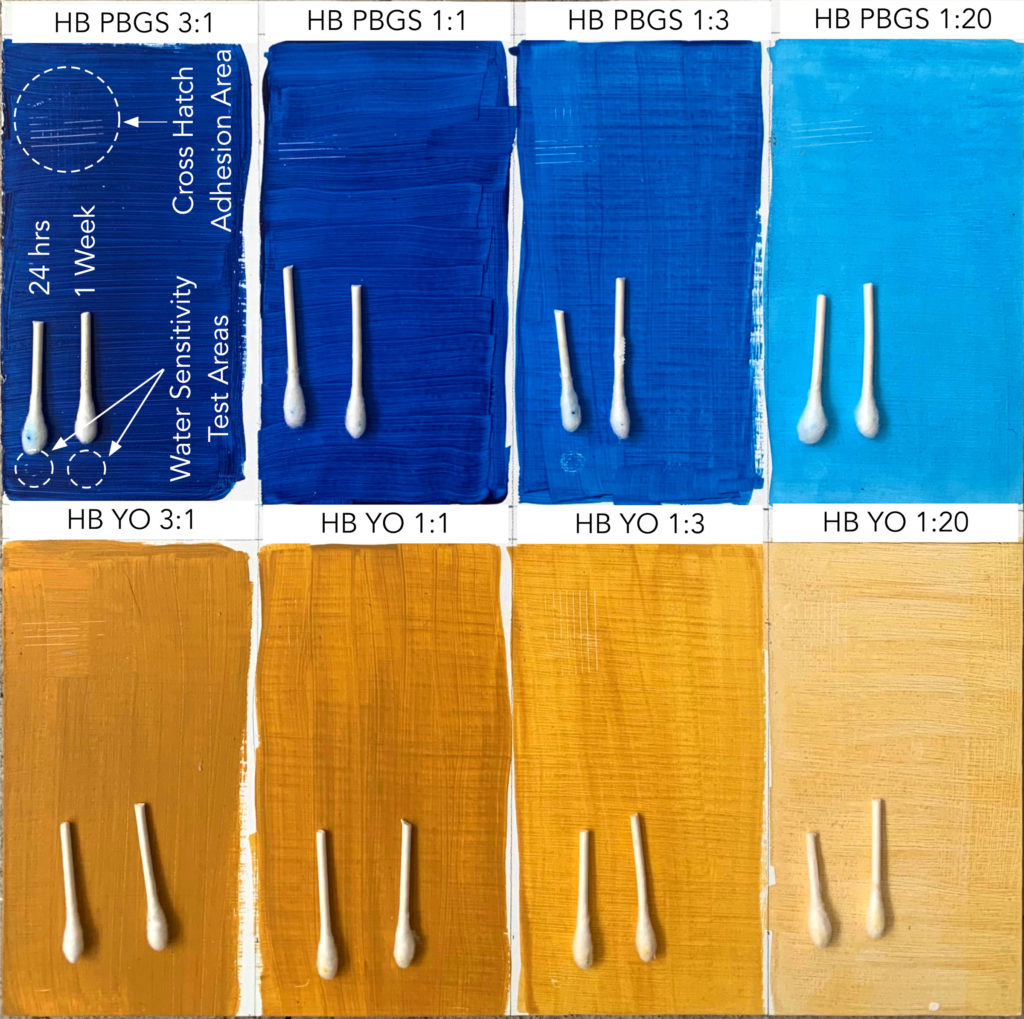

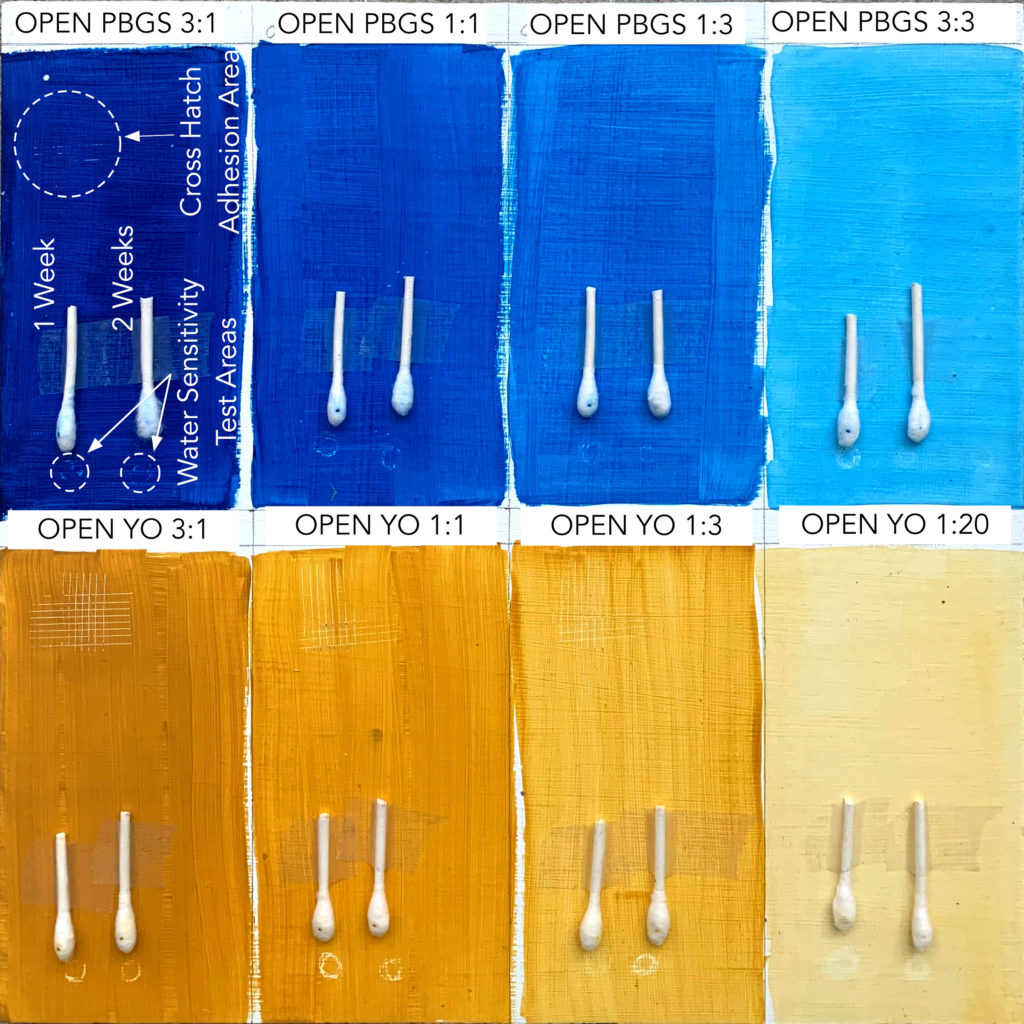

We tested GOLDEN Heavy Body, Fluid, High Flow and OPEN Acrylics on both wood panels and aluminum plates primed with GOLDEN Gesso. In terms of color, we chose Yellow Oxide (YO) and Phthalo Blue Green Shade (PBGS) as typical of our paint lines overall, and Raw Umber (RU) and Anthraquinone Blue as being outliers that were among the most water sensitive. The paints were tested as-is and blended with water in volume ratios of 3:1, 1:1, 1:3, 1:20 and 1:100.

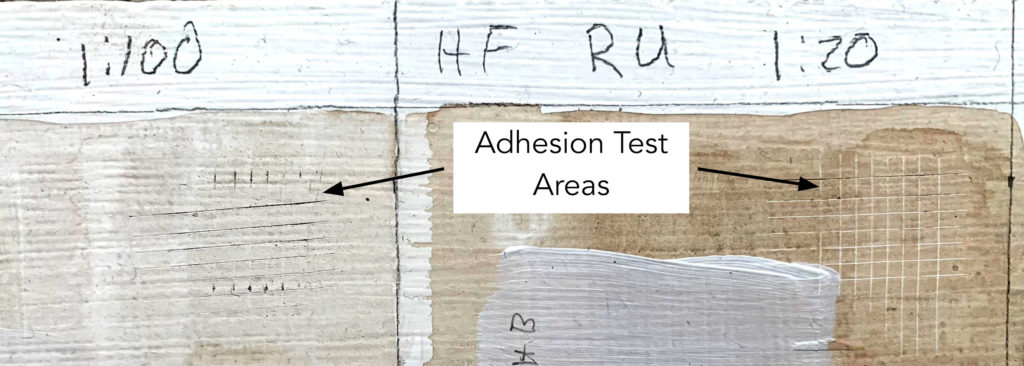

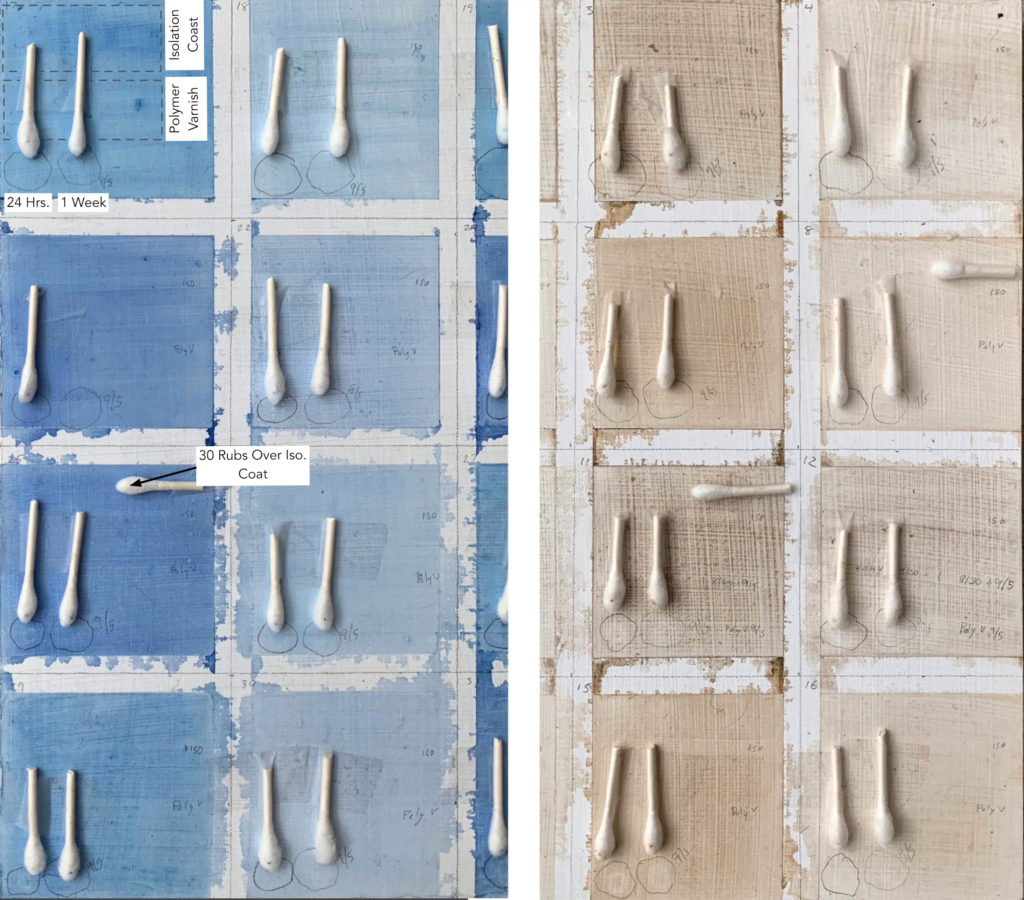

The testing was extremely strenuous and went far beyond what anyone would normally encounter. Adhesion was tested at 24 hrs and 1 week using ASTM’s Cross Hatch Adhesion Test (D3359). Water sensitivity was tested at the same intervals, using a cotton swab dampened with water and rubbed 10 times while pressing downward with very firm pressure, as well as brushing another area 20 times with water. The only exception was OPEN, which we tested at 1 and 2-week intervals instead, due to its slow curing time. Additionally, we tested for any color lift when brushing on Heavy Body or OPEN Titanium White, Polymer Varnish, or our Isolation Coat recipe. Finally, we pre-made 1:5 and 1:10 blends of water with either Fluid Matte Medium or High Flow Medium, then used those to thin Raw Umber and Anthraquinone Blue at 1:20 and 1:100 ratios. These were then tested for any sensitivity at 24 hrs and 1 week. In all, there were some 175 samples generating well more than 1,000 data points.

Some Limitations

While our results should hold true on top of other GOLDEN Paints, Grounds, Gels, and Mediums, because there are so many variables and combinations, it is always important to test for your application. Also, keep in mind that glossy acrylic surfaces might cause some wetting issues when applying highly diluted paints. We provide some suggestions for dealing with that later on. We did not look at direct adhesion to non-absorbent surfaces like plastic and metal, so always test those before use as well. For suggestions on how to test, please see the Just Paint article Will It Stick? Simple Adhesion Testing In Your Studio. Furthermore, our results would not be applicable to materials like glass or glazed ceramics that acrylics inherently have poor to moderate adhesion to without the use of special primers, mediums, or preparations. Finally, we did not test other brands of acrylics and cannot speak to how those would perform in similar tests.

Results

Adhesion

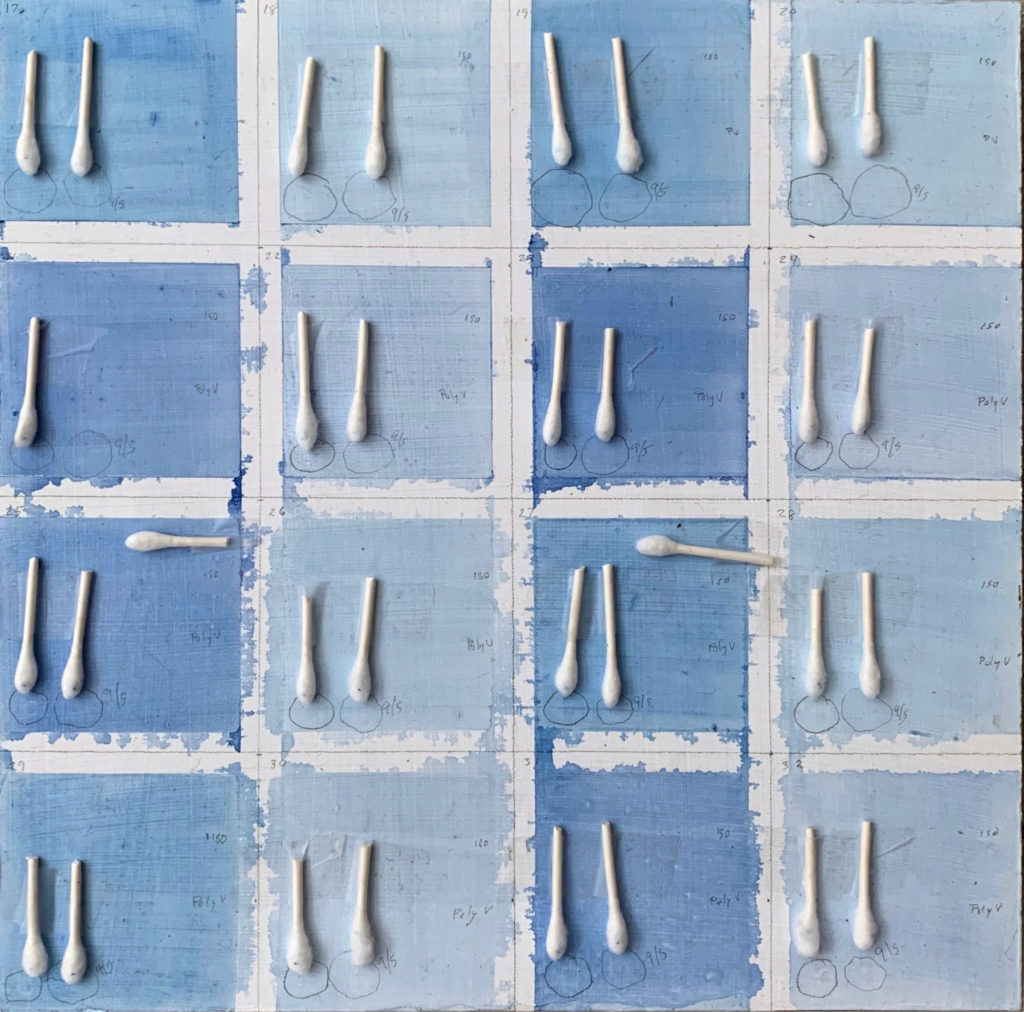

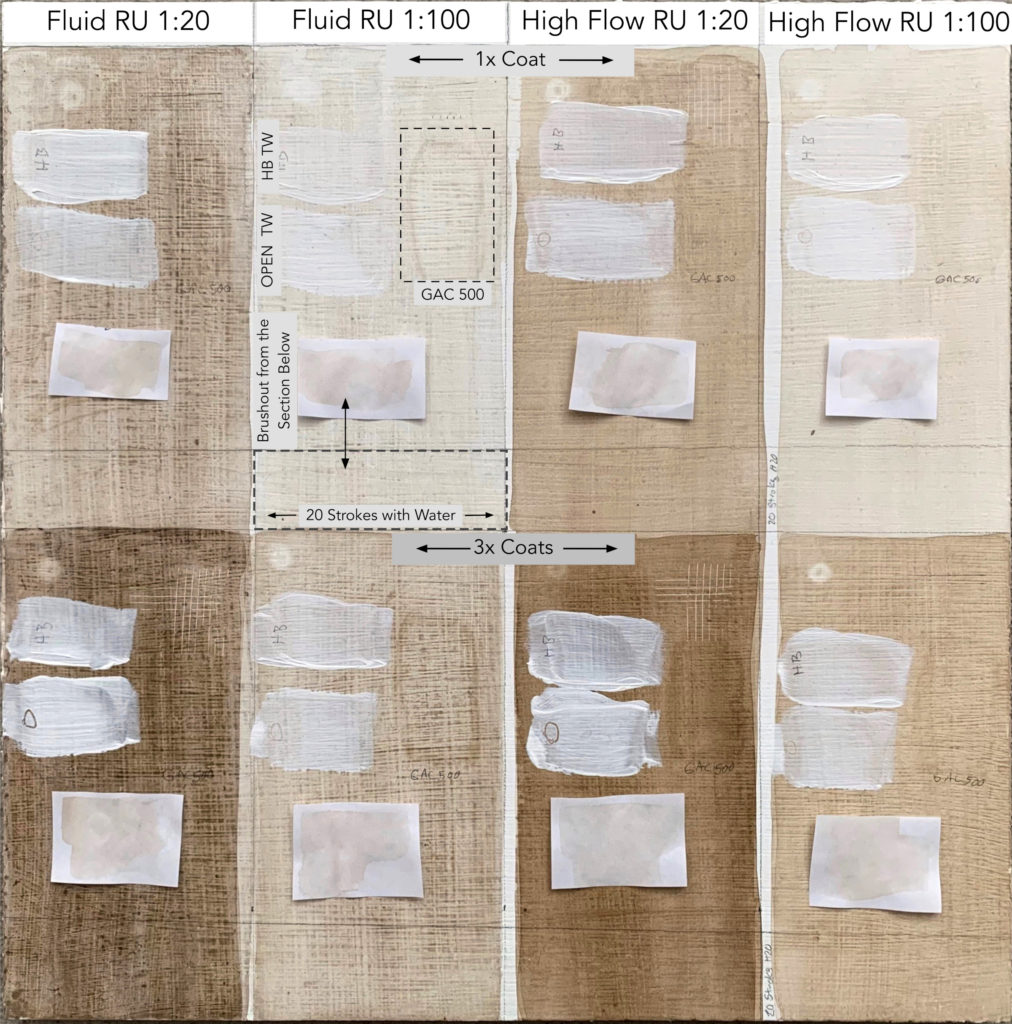

As mentioned, even thinning the paint with 100 parts water did not lead to any adhesion failure. (Image 1) Of course, adding that much water will also turn paint into a stain with no film thickness to speak of. By that point the paint is soaking into the absorbent acrylic gesso the same way watercolor washes will get absorbed by paper. However, all the acrylic blends, even the 1:3 or 1:20 ratios, which still dried with a discernible film, performed well. At least on an acrylic ground, adhesion is simply not a concern.

Sensitivity to Water and Other Products

Colors with a Typical Range of Sensitivity: Phthalo Blue GS and Yellow Oxide

Between these two typical colors from our Heavy Body, Fluid, and High Flow lines, only Phthalo Blue GS showed some slight water sensitivity at the 24 hr mark, and that disappeared when it was retested after 1 week. (Image 2)

Our OPEN line, by contrast, was tested at 1 and 2 weeks since it takes longer to lock down. While the cotton swab was able to pick up more color, the color was largely restricted to a concentrated dot, which is more about the relatively soft film being physically rubbed off than color lifting per se. It is also important to keep in mind that the cotton swab test is a very aggressive one, and this degree of rubbing would rarely be encountered. (Image 3)

Paints with Higher Sensitivity: Raw Umber and Anthraquinone Blue

Because we had so few failures with Phthalo Blue and Yellow Oxide, we decided to continue the testing using Anthraquinone Blue and Raw Umber, a pair of highly sensitive colors representing a ‘worst-case scenario’. We left OPEN out of these additional rounds since it presented such unique issues due to its slow drying formula. Instead, we opted for High Flow and Fluid Acrylics, since they are frequently used for wash applications, plus any results from the Fluids would be applicable to Heavy Body as well. Finally, we increased the maximum water additions and tested colors at both 1:20 and 1:100 ratios; far past what almost anyone would use.

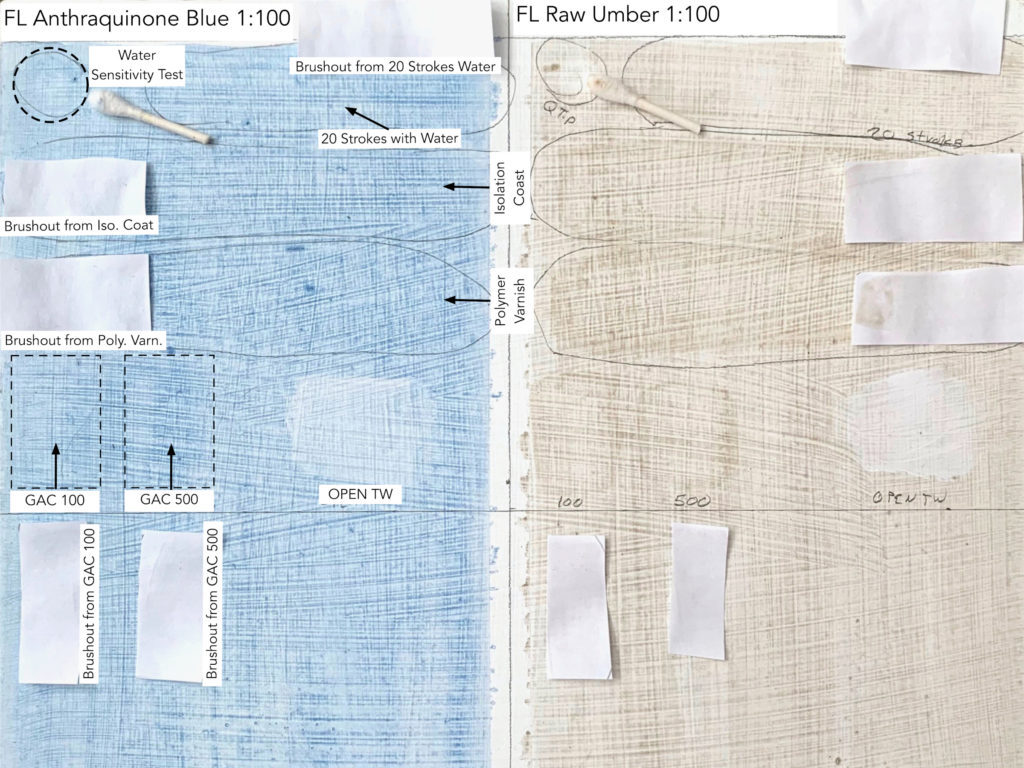

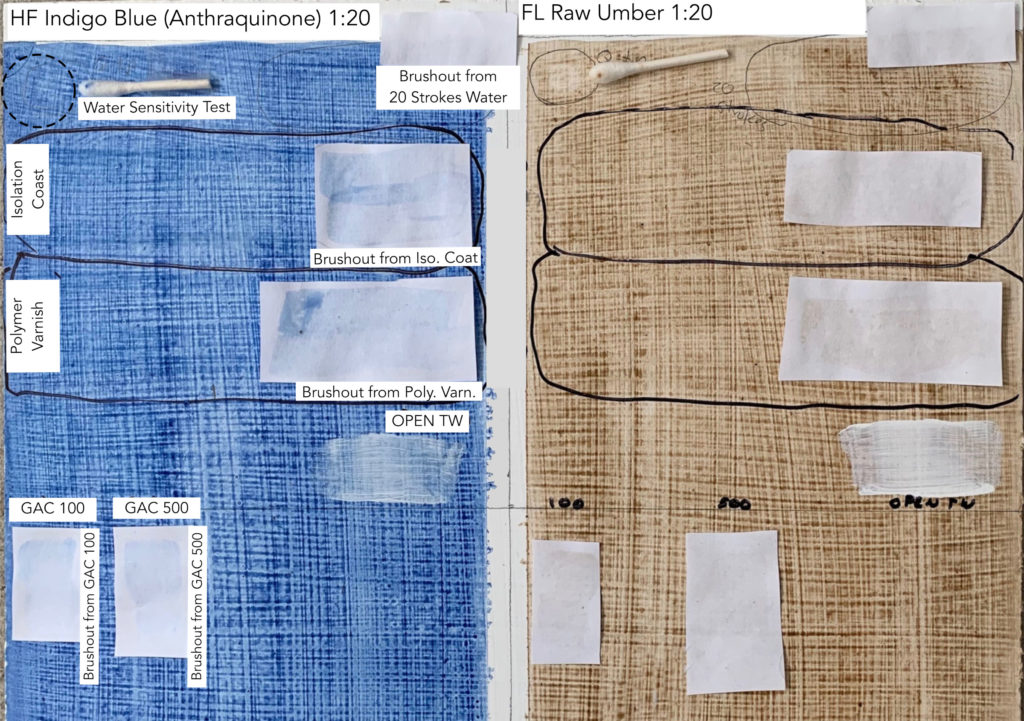

Water Sensitivity

In judging water sensitivity, we wanted to add something less physically aggressive than the cotton swab test. We therefore decided to brush water 20 times over a small section on the test panels, then wipe the brush on a clean piece of paper to see if it had picked up any residue. And indeed, for the Raw Umber in particular, you could see a very light wash of color left on the sheet. But even then, the area on the panel where we had brushed, appeared untouched. For most artists under most circumstances, we felt, this amount of sensitivity could be acceptable, especially as most people would be doing far fewer passes than we did. And even at the higher level, it certainly was not anywhere near the warnings of complete lifting expressed by some. In the cotton swab area, enough color was lifted to still be a concern if someone was rubbing or working the surface more forcefully.

Sensitivity to Other Products

Of course, simply rubbing or brushing water by itself on a surface is just one type of testing, and is not something artists might do frequently outside of cleaning the surface, or using very watered down washes. So we also tested other types of applications: brushing on a layer of paint (in this case, Heavy Body and OPEN Titanium White), adding an isolation coat of 2 parts Soft Gel Gloss and 1 part water, brushing on GAC 100 and 500, and finally applying our Polymer Varnish. (Image 5)

While the Titanium White brush outs all looked fine, the other products lifted color to one degree or another, varying by paint line and pigment. While none entailed a significant loss of color, an artist might certainly notice it while applying an Isolation Coat or brushing a medium over adjacent colors. It is also worth noting that the Polymer Varnish lifted the most color, likely due to its unique composition and amine levels. Much more problematic, however, was the appearance of dark rings around the outer edge where many of the clear mediums and varnish had been applied, in particular, to highly diluted Raw Umber; almost certainly evidence of suspended pigments that were lifted and deposited there in the process of drying. (Images 4 & 5) However, even if limited to Raw Umber, it was clearly an issue that needed to be remedied.

One Easy Fix for the Increase in Sensitivity

We entered round 3 of our testing hoping that a simple blend of some acrylic medium and water could be an easy solution to the earlier issues. We therefore tested mixing Fluid Matte Medium or High Flow Medium at both 1:5 and 1:10 ratios with water, then blending each of those at 1:20 and 1:100 ratios with paint. These were brushed onto an acrylic gessoed panel where, after just 24 hrs, we saw almost no evidence of sensitivity outside of a handful of cases, and even those all showed improvement when reexamined a week later. Also, when we tested the cotton swab on top of an area with an isolation coat, even if we rubbed 30 times while using a lot of pressure, we could not get any amount of color to lift. And reassuringly, the unsightly dark rings that we saw earlier were no longer an issue. Lastly, and perhaps just as importantly, these thinned down mixtures of water and medium really felt indistinguishable from using water alone.

Changes to Other Properties

Handling, Sheen, Wetting, and Stability in Storage

When thinning paints with water more than just adhesion or sensitivity can be impacted. The entire feel and performance of the paints change as well, and can often be a major reason for wanting to use or add mediums rather than water alone.

- Handling: the more water that is added, the more the paint will feel….well, watery! Which of course is not a surprise, but certainly something to be aware of. Otherwise the rich transparent glaze you were hoping for might appear more like a thin watercolor wash after it dries. And of course, thinned down paint can cause runs on a vertical surface, puddle on a flat one, or cause things like paper to buckle and warp. So always do some testing to make sure that just adding water gives you what you want. If it doesn’t, and you want something thicker in feel or richer in binder, then try experimenting with different ratios of water and acrylic medium until you find the balance you are looking for. Or even try using our High Flow Medium by itself, which is the thinnest of our mediums and can often act as an alternative to water while maintaining a high binder level and imparting a glossy appearance.

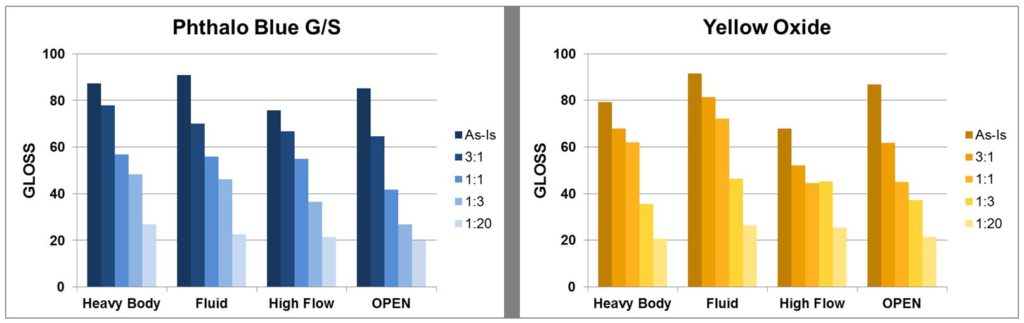

- Sheen: The more water you add, the more matte the paint will become, regardless of what sheen or line of paint you start with. Chart 1 shows the change in gloss for two of the colors as they were increasingly thinned down. This can also impact the appearance since matte colors appear lighter and less saturated. If this is a concern, adding mediums can help give you more control in this area. However, at the ratios that we blended mediums and water in our tests (1:5 and 1:10), the results still appeared fairly matte, so you would need to continue adjusting the ratio to get the sheen you want. Or again, look to using High Flow Medium by itself for a glossy film.

- Wetting: The acrylic lines are formulated with an optimal level of surfactants that, among other things, will help them wet-out a variety of surfaces more easily. As more water is added, these surfactants get diluted and you might find that the paint begins to bead up or crawl on some surfaces, like metal or some plastics, or resists penetrating into raw canvas. To solve this you could try mixing more medium with the water, or add a tiny amount of our Wetting Agent into the water you plan to use, making sure to follow the directions very carefully as this is a highly concentrated material and adding too much will cause other problems.

- Storage: The more watered down the paint, the more the pigment particles will start to separate out and gravitate towards the bottom. To prevent this while working, you will need to stir periodically to keep them in suspension. It is also best to only mix up as much as you need in the very short term as very thinned out paints can develop mold since the overall pH starts to move towards neutral and the biocides that were originally added have become too diluted to be effective. If you need to make up larger quantities, always use distilled water and store in clean uncontaminated containers. Also, adding a very small amount of unscented household ammonia (about a capful per gallon of water) will maintain an alkaline pH that discourages spoilage.

Our Recommendations

Given all of the results, where do we end up in terms of recommendations? While there is nothing wrong with our older advice of a 1:1 ratio, which is both easy to remember and eyeball in mixtures, it remains an extremely conservative limit and we want people to feel more confident and comfortable exploring mixtures well above that. We hope the guidelines below will help:

First, just a reminder that the following guidelines are for using GOLDEN Heavy Body, Fluids, and High Flow Acrylics on top of GOLDEN Gesso, Mediums, or Grounds, as well as other layers of those same paint lines. We can not speak to the performance of other brands of acrylics.

And, even more importantly: Always Test for your application to make sure it meets your needs and expectations.

Adhesion

- In all our testing adhesion was never an issue, even at 1 part paint to 100 parts water.

Up to 1:20 Paint to Water

Water Sensitivity

- While for most colors this should remain a non-issue, even at higher levels of dilution, we did see an increase in water sensitivity for things like Raw Umber, with its naturally high clay content, or the more dye-like Anthraquinone Blue. Other examples will most likely vary with paint lines and the nature of your application. If you simply want to take the guesswork out of it, you can always blend a minimum of 1 part GOLDEN Acrylic Medium, like our Fluid Matte Medium, Gloss Medium, GAC 100, or High Flow Medium, and 10 parts water. Then thin to your heart’s content. And if ever in doubt, water sensitivity is super easy to test with a cotton swab or piece of cotton fabric and some water. Just let the application dry completely and know that water sensitivity will often improve with time.

Sensitivity to Other Products

- While we only tested Heavy Body and OPEN Titanium Whites, we do not anticipate any problems applying additional layers of GOLDEN Acrylic Colors.

- Applying Polymer Varnish or GOLDEN Mediums, including our brush-on Isolation Coat recipe of Soft Gel Gloss and water, directly to highly thinned and water sensitive colors, can cause some color lift. And for some colors, like Raw Umber, dark halos might develop around the outer edges of the application. If needed, a sprayed on Isolation Coat might be required, or use of our Archival Varnish as a way to decrease sensitivity before applying further layers. Alternatively, follow instructions below to increase film durability.

Above a 1:20 ratio of paint to water, or whenever needing decreased water sensitivity

- We recommend using a minimum of 1 part GOLDEN Medium to 10 parts water to thin acrylics above a 1:20 ratio, or whenever more durability is needed. Doing so will increase film strength and lower sensitivity to both water and other GOLDEN Mediums and Varnishes.

Note on OPEN Acrylics and Mediums

With OPEN Acrylics, adding large amounts of water gets a little more complicated as it will greatly reduce the working time of the paint, which is usually the main reason people use it in the first place. And of course, as we shared, water sensitivity is generally higher in this line. That said, just in terms of adhesion, we saw no problems in our tests which went as high as a 1:20 ratio of OPEN to water. If wanting to hold onto more of the working time of the OPEN, and still create a wash, explore using either our OPEN Thinner or a blend of water and OPEN Medium.

Some thinned down GOLDEN Acrylic Colors showed increased sensitivity to OPEN Thinner, which has a high level of glycols. This sensitivity might extend to other OPEN Products, so always test if using on top of highly thinned down washes. Use of an Isolation Coat, when possible, would be recommended, or thin the initial layers of acrylics using our recommended minimum blend of 1 part medium to 10 parts water

Exceptional technical article. The hard work is appreciated! Now…where did I put that water…

Hi Michael – Thank you so much!! We love doing this type of research so much that we sometimes forget to think of it as hard work! But more seriously – we definitely appreciate hearing that articles like this are appreciated and valued. It makes it all worth the effort – truly.

so helpful

and I have so much airbrush paint ,hope I can use a little

do not airbrush any longer.

great site thank you

linda

Hi Linda –

Glad the article was helpful! The Airbrush Colors should perform very similarly to the High Flow paints we tested, so feel fairly confident you should be able to use them in the same ways. Just follow the same guidelines if wanting to dilute them with water.

Sarah

I never add water to Golden acrylics Colors.

As I never à add water to my wine…

I neverthless mix some Golden mediums to golden HB or fluid Colors. But never water.

Consequently I use a lot of pure from the packing or container, Golden colors. My technique is applying colors withe squeegees on the canvas. Many layers wet on wet.

One of the wonderful things about acrylics is how it lends itself to so many different approaches – but also have to admit that your comment made me smile with its analogy to wine.

Thank you, this information is super. I’ve been using your various mediums with OPEN acrylics for about 6 years now, and I really enjoy working with them.

Hi Ann – Thank you for the warm words of appreciation, and for being such a dedicated fan of our products! It means a lot to us and we never take that for granted.

The most important areas of testing, I’ve found, are those topics that “everyone knows”. When I’ve seen other acrylic painters add more and more water for glazing, I couldn’t help but wonder where the breaking point was. Thanks so much for sussing out that information.

I can’t help but wonder what the long-term effects (decades or more) of high dilutions are, or how they stand up to the changes in the support over time due to temperature and hydration?

Hi CJ – First, thanks for the positive feedback and we couldn’t agree more, that it is often the handed down assumptions that might need as much focus as the great unknowns.

Your questions are great ones. Luckily acrylics remain incredibly stable. in terms of their final properties, and while all things age and change, we wouldn’t expect these films to suddenly take a turn for the worse and lose flexibility or an increase in sensitivity. But there are some things worth noting. For example, as the acrylics become more and more matte in the process of dilution, they naturally become more vulnerable to dirt accumulation and surface abrasion, and without an isolation coat or varnish to protect them, future cleaning and repair would be a much more delicate process. So we would certainly be an advocate for adding those protective layers, although we also understand that that will alter the visual aesthetic of the piece. And finally, as the pigments become less completely bound in an acrylic binder, they start to assume some of the vulnerabilities of watercolor in terms of the potential fading of less permanent ones, or for any pigments more sensitive to exposure to the environment.

Thank you. In my conversations with other artists about acrylics, one of the main criticisms besides the rapid drying, was the complicated additives and the lack of using “good old water” to work the paint. In workshops I learned and held fast to the information concerning the hydrophilic nature of acrylic paint. So, now, you’ve expanded that information (and the limits) which is a breath of fresh air and a great vindication of the flexibility one has with acrylics, especially Golden.

Hi Stephen – Its great to hear that this article helps confirm what you already intuitively felt, not to mention provide some ‘vindication’! And hopefully, as it is shared and makes its way to a larger audience, it will be able to change the misperceptions around acrylics, which truly remains one of the most versatile mediums one can use.

Wonderful article. I thinned down acrylic for years but would only say I used some water to thin the paint because so many frowned on it. I also paint on fabric using only water to thin. had problems. Now if someone starts whining about water being a poor additive, I can say, “Go read the article on the Golden site.” Thank you

Hi Gloria – Thank you for the comment and warm feedback. Also great to hear that you feel you now have a place to point people to. It’s true that there are a lot of misconceptions out there and we will continue to do what we can to help provide solid information.

I usually work with watercolour on paper but I am able to do the same, get the same feel, with Fluid on canvas. Preparing the canvas with correct Gesso is crucial and took a lot of testing. Thank you so much for this thorough information!

Hi Stefan – You are so welcome! Definitely Fluids and High Flow colors can be used in just that way, thinning them down to make watercolor-like washes. We are so glad that you found the information useful.

what would be correct gesso to apply thined down fluid

Hi Jane – It sounds like you are asking which gesso you should use under thinned down paints? If not let us know. In general our regular Gesso will serve most needs and is what we sued in our testing. However, if you wanted something that was closer to painting on watercolor paper, you can look at our Absorbent Ground which you would apply on top of our gesso to allow for watercolor-like stains and bleeding, softer edges:

https://www.goldenpaints.com/technicalinfo/technicalinfo_absorb

Beyond those two, however, you are also free to use almost any of our Gels or Pastes as a ground for acrylic washes. For example, Light Molding Paste offers a unique sponge-like texture, while Fiber Paste forms a hard but still absorbent surface similar to unbleached paper-pulp. Overall, matte products will provide more tooth and absorbency then gloss ones, and experimenting with both – or even blending the two – can give you a range of possible effects. Hope that helps, and if you have any other questions just let us know.

Golden’s light molding paste is easily becoming my favorite ground (over gesso) for acrylics, and watercolors, even more than absorbent grounds, which I still like 😊 I did have a question, how much watercolor paint can I add to an acrylic paint and still not need to apply a special isolation coat etc to the final painting? There’s something very nice, usually anyways, that happens with an acrylic color for me when I add a dab or so of watercolor paint. Thanks so much!

Adan

Hi Adan –

Thanks for the question. First off, just to let you know, we consider any percentage of watercolors added to acrylics to be experimental, but it sounds like you are comfortable with that. In terms of amounts that can be added before seeing water sensitivity and color lift, there is really no way to know – different brands and different colors will all have different levels. So some testing will be required on your part. The best way is to add varying controlled amounts of watercolor to, say, a clear gel, let fully dry, then use a wet Q-tip moistened with water to see if color lifts up. You might also test how an isolation coat does, as well as whatever varnish you might use if needed. Basically the same testing you see in the article. That said, if we had to give a likely maximum amount, it would be in the neighborhood of 10-15% at most. But again, the actual results could be variable and dependent on things that we have not tested ourselves, so in the end would still be considered experimental.

Hope that helps –

Sarah

It’s nice to work with a company that makes research and share knowledge with users

Hi Alessandro. Thanks! And it’s incredibly nice for us to have customers that find this work valuable, and are dedicated to our products. In a very real sense, we couldn’t do what we do without the support of people like you.

Thanks for the article. It is really well done. It reaffirms my current process, where the use of water or some form of medium has more to do with feel and look, and less to do with worrying about whether or not I am going to have a technical issue.

Hi Hal – Glad you found the article useful and that it confirms your approach. A lot of what we set out to do was exactly that – to give artists like you a bit more confidence when working with thinned down acrylics.

Glad to read. Not been in the habit of ‘varnishing’ or applying a protective coating to finished works, but in light of your work I may well do so as you seem to think it advisable to stop any long term degeneration of colour

Hi Patrick – We feel that varnishing is always a choice and, as much as protecting the painting, it still needs to work aesthetically as well. You might like this video that explores that question: Should you varnish your painting? In general acrylics, it is true, are more vulnerable to dirt and abrasion, especially if very thinned down, but the colors should not degenerate unless using less lightfast ones and placing them in strong light. But if concerned, it is true that varnished paintings are certainly better protected in the long run and something we do believe in, regardless of how one might paint.

Your article is informative and is in agreement with what I have learned through trial and error. I have been flooding and pouring water-thinned acrylics onto large watercolor papers, using flow and fluid acrylics and liquified gel mediums. This winter, I began painting with liquid watercolors and using disperse pigments in Aquazol—along with my acrylic process described above—in various combinations. It all works well for the first pass, which I let dry.

The problem is how to fix or isolate that initial layer, so I can continue with a second pass and additional layers painted over that. Can you recommend some way to lock in the watercolor and pigments without disrupting the original painted layer? I realize it may not be possible and using watercolors is a fatal flaw. Or maybe not?

Hi Jeffrey –

The best way would be to use a solvent based acrylic to lock things down. We would recommend our Archival varnish, which we use a lot as a way to lock down watercolors or lessen the water sensitivity of inkjet prints and allow for additional layers to be applied on top. Three layers might be needed depending on how sensitive the watercolors are, so you might want to test. Once that is dried you could then continue with acrylics, or even apply a layer of, say, Fluid Matte Medium as a form of translucent ground. Any additional watercolor at this point might feel very different, but you can do some tests. Just understand that the sandwich of layers get increasingly complicated the more different mediums you use. So I think the best would be to use the watercolors in those initial layers, apply Archival Varnish on top of those sections, then continue with acrylics from there.

Brilliant article and very informative and interesting. Thanks as always Sarah! 🙂

You are very welcome Phillip – and equally, as always, thanks for the warm feedback. We appreciate it!

I hope you can answer a question here.

I am especially interested in your article because 2 days ago, I watered down a modeling paste (not Golden) and it flaked all over the place.

I’m hoping that Golden has something that I can apply over the dried, frail paste that will stabilize it.

I was thinking matte medium.

Unfortunately, I applied the stuff over a huge number of cardboard elements, and removing it would

be too time consuming to even be worthwhile.

Thanks for the excellent article.

Hi Jen – I saw that you are also working with one of our Materials and Applications Specialists and unfortunately my advice would be similar to hers. Once there is a failure between a coating and the ground underneath, applying an additional coating on top will rarely solve the adhesion issue. At least in a very longterm durable way. You might get enough additional stability for a short term need, but there would be no guarantees. So starting fresh, unfortunately, is the best option if this is meant as a permanent or semi-permanent piece. If you opt instead to try and stabilize the remaining pieces more, your best bet would be using a very fluid acrylic (such as our Fluid Matte Medium, with possibly a little water added, or our High Flow Medium) which could hopefully soak through or under enough to anchor them a little more.

This is a very informative article, thank you. Could you let me know if you know of, or have any information about the long term stability of water diluted acrylics? I tend to premix my paints or washes to a certain consistency in large amounts to reuse at a later time across repeat projects but I find there’s increased separation with paints premixed with water. My suspicion is that I should be using deionized water to avoid molecular binding over time. My experience is that the matte medium especially is susceptible to falling out of solution. I’m usually using the additional medium as you were to keep a better ration of binder while still thinning.

Anyways, thanks for any help in advance!

Cheers

Hi Dan -Given how thin your dilutions sound, and simply the inherent nature of pigments to settle out of watery mixtures, we do not think that deionized water will do all that much, although particularly hard water could also make things slightly worse. Ultimately, however, we think your solutions lie elsewhere. If you haven’t already, give our High Flow Acrylics and High Flow Medium a try as they are already optimized to be stable a much lower viscosities and actually have similar pigment load as our Fluid and Heavy Body lines. So they are not simply ‘watered-down’ Fluids, but a truly highly pigmented ink-like paint. It will not be as thin as water, but you might also find that you do not have to add as much water to begin with in order to get the effects you want.That said, and as I mention in the article, pigments and matting agents will settle over time the thinner the mix gets and there is no easy way around that. The High Flow is likely as thin as one can get most pigments to stay in suspension, at least over the course of a working session, but we still advise gently shaking the bottles before each use. It’s a form of humble bow to the laws of gravity.

We wish we had a better solution for you – no pun intended. And at least take comfort in the fact that all painters working with thin washes, from Helen Frankenthaler on, have had to deal with similar issues.

Hello,

I just want to make sure I understand your article correctly. So, as long as my ‘water’ consists of 10 parts water to 1 part acrylic medium, I can add any amount of this ‘water’ to a paint without ill effects?

For myself, I’d have trouble eyeballing a 1:10 ratio. Could I just pull or drop a dollop of medium into a mix with water and be generally safe?

I’ve been so programmed NOT to water down my paint with water, so this is great news — that I can feel free to use your acrylic paints in a watercolor-like/washy fashion without fear.

I’m also wondering if the rules around retarder are still accurate, or if you could add as much as you needed. (I don’t use it, but I know people who add more than 15% and have had no ill effects, at least in the short term.)

Hi Lisa – Yes, that is, in a nutshell, the implications of the testing. Another way to think about it is that the paints thinned down 1:20 with water did quite well, which means that the binder in those paints was diluted by a similar amount. By doing a 1:10 mix of medium to water you are basically guaranteed to have twice as much binder as the 1:20 paint, so that should build in enough wiggle room to be safe. If ever nervous, one can always do a 1:5 mix which, especially if using the High Flow Medium, will still feel very fluid.

In terms of eyeballing, all my tests were done in volume ratios, so you could do 1 tablespoon medium and 10 tablespoons water, or use the ratio of 1.5 Tablespoons medium to 8 oz. of water, 3 tablespoons to a pint, etc.. If you use distilled water, and clean containers, you can make up more than you need for one session as well. It should keep fine, but if using Fluid Matte Medium you might want to gently shake the bottle before use to make sure the matting solids are in suspension.

On the retarder front, we do still recommend a 15% max addition as being safe, but it is also true that if working directly on an absorbent surface like paper or canvas, either raw or gessoed, you can get away with higher levels as it will be pulled down into those substrates and not get trapped in the paint film. And you can also get away with a bit more if working with very thinned out washes – again because the retarder will tend to evaporate away. The main concern is having it linger in the paint and causing increased water sensitivity or preventing the film from fully locking down until it can evaporate away. If nervous working with retarder you can always just use the Glazing Liquid, which has the 15% already built in, and use that to your heart’s content as well as you can never exceed the recommendation!

Hope that helps and happy painting!

Hi Sarah,

Your above comment is with regards to the retarder, but I have a similar query about the OPEN Thinner. I can see in the additives page that it says:

“Retarder is an additive used to increase the open (drying) time of acrylic paints. Useful for wet in wet techniques and reducing skinning on the palette. (Item# 3580)

OPEN Thinner is a water-based additive for thinning the consistency of OPEN Acrylic Colors and Mediums without altering drying time. It also maintains and adjusts the workability of OPEN colors on palettes, and can be used as a thin-bodied retarder with Heavy Body or Fluid Acrylic colors. Because OPEN Thinner contains no binders, it does not form a film and should only be 25% or less of mixtures with acrylic colors and mediums (one part OPEN Thinner to three or more parts paint or meduim). (Item# 3595)

For more information on OPEN Thinner see the Product Information Sheet.

Neither Retarder nor OPEN thinner contain binding agents. To ensure adhesion, it is recommended that the addition of Retarder not exceed 15% (1:6), and OPEN Thinner should not exceed 25% (1:3) when mixed with colors or mediums. ”

And in the tests above you said that:

“Adhesion

In all our testing adhesion was never an issue, even at 1 part paint to 100 parts water.”

So, is the limit on the thinner more to do with the issue of the additives being trapped in the paint film rather than adhesion concerns? However the information you have regarding GOLDEN open says that “OPEN Thinner should not be used in thick applications. Applications of more than 1/16″ may result in:

Excessively long drying periods

Persistently soft, higher tack feel

Translucent layers that remain cloudy”

Does this mean that paint that is thin due to more thinner being used will have the same issues, but will eventually dry too?

Hi Richard – You basically have it correct. The big concern with retarders is that they can get trapped in thick films, causing all those issues we mention, and as long as they are still present you get a lot of water sensitivity, which would mean much more color lift. It is also why we note, towards the end, that OPEN Acrylics are a different case in many ways because of the inherently longer open time and water sensitivity. That said, a lot will also have to do with the absorbency of the surface you paint on. For example, if working directly on paper or raw canvas, you could probably get away with more OPEN Thinner than we recommend since the retarders will be drawn down as well as evaporating up. But we think its best to avoid overloading with retarder. If you want to incorporate them into your thinning, then work with our Glazing Liquid, which has the recommended max of 15% and you can thin that down further if needed.

Good Day/Evening, Ms. Cathy.

Does the 1:20 ratio you have mentioned also hold true for your mediums such as GAC100? I managed to purchase a sample of the rarely-manufactured pigment Egyptian blue (PB31) and would want to use your medium to make an Egyptian blue acrylic paint. But because I was only able to purchase a small amount, I want to make the formula last for as long as I could.

Hi Clarence – Yes, the 1:20 ratio would include GAC 100. Also, if you are trying to make acrylic paint from a dry pigment, we recommend looking at our article, Just Make Paint, which covers some of the steps and issues to be aware of:

https://justpaint.org/just-make-paint/

At the most basic level, and assuming there are no wetting-out issues, you could simply start by blending the Egyptian Blue with GAC 100 to make a strong dispersion. A 1:1 ratio by weight is a place to start but adjust as needed to get a creamy paste. Then you can add that concentrated dispersion into whatever medium or gel you want to use as the base of your paint. Because of the thinness of the dispersion, you will want to choose a medium/gel thicker than you want for the final product. For example, use the Extra Heavy Gel for a Heavy Body type consistency, or try the Soft Gel for something more fluid. If you run into issues or have questions, of course, let us know. but overall once you have your paint made, you should be able to thin it with water at the 1:20 level, but of course because of the variability of a handmade paint, it is worth testing before committing to anything of importance.

I just recently watched the 2003 documentary film “Agnes Martin: With My Back to the World”. She is shown applying very thin watery-looking washes of color which she says is drying very fast, to a large canvas that she had gessoed herself. On a work table against one wall are large jugs of Golden paint.

Thank you for this information. It has completely changed my understanding of how your paints can be safely applied.

Hi Susan. I LOVE that film and know exactly the scene you are talking about! And so glad this has broadened your understanding of what might be possible to do with our paints and still feel things are durable. Happy painting!

Hi. Can I use pre-gessoed canvases in this way? They have less “tooth” than gesso applied on paper or boards. Perhaps add an additional layer of Golden gesso to the canvas?

Hi Betsy –

We always like recommending adding a coat of high-quality gesso on top of any preprimed canvas as a way to know that you have a good and consistent ground to paint on. We definitely know that our own gesso should be fine with applications containing a lot of water, and indeed, most of the testing we did for this article had a layer of our gesso underneath as we felt this was closer to what artists will experience. If you have any other questions, simply let us know – or email [email protected].

I appreciate the work you put into this article. However I do not agree that you can add water to acrylic paints when used on non-porous surfaces (even gessoed canvas). Your tests were not over 10 or 20 years – this is when the paint can crack or flake. Follow what is recommended by the manufacturer (most are ok with 30% water). I do agree you can use as much water as you like when painting on absorbent surfaces such as paper (like watercolor). Here’s one article that explains it clearly: http://rfasupplies.com/dont-use-water-to-thin-your-acrylics-a-review-of-acrylic-mediums/

Hi Mary – Thank you for sharing your thoughts and concerns. We totally agree that on truly nonabsorbent surfaces, like glass, metal, and some plastics, good adhesion would require proper surface preparation, the addition of mediums, and often the use of special primers. And we do state in the article that the results and our recommendations were limited to the use of our acrylics on top of our gesso.

In terms of adhesion to our gesso, this research and article were meant to counter the frequent misinformation we often find around thinning acrylics. We cannot, of course, speak for other manufacturers and did not test their paints, but as one of the major manufacturers of acrylics with an unmatched 40-year record of research in this field, we do stand behind these findings in regards to our own products. While it is true these specific tests were recent, keep in mind we have worked with artists and tested applications involving thinned-down acrylics over many decades and have not had the cracking or flaking you mention.

Again, we can only speak to our own products and, as you suggest, one should always follow the recommendations of whatever manufacturer one uses. These just happen to be ours 🙂

Thank you so much for this article Sarah. I paint on cradled birch panels, and use my Golden acrylics like watercolours, very thinned down…. even leaving drips run down in the painting. I love that effect. After the painting is completed and dry, I varnish it with Golden Archival spray. Will that guarantee that the paint will continue to adhere to the panel ?

Thank you,

Karole

Hi Karole –

You don’t mention if the birch panels have a ground on them or not. I am assuming so, in which case we would have no concerns about the adhesion of the acrylics. As our testing showed, even very dilute mixtures adhered well to acrylic gesso. However if using a lot of water, then one should protect against SID (Support Induced Discoloration) which you can learn about here:

Blocking Support Induced Discoloration

As for the varnish, it will certainly help protect the washes from dirt and dust and should eliminate any water sensitivity, while of course providing protection from UV. But in general, varnishes will not solve adhesion issues but again, in this case, I don’t think that is even a concern.

One note, in case you are painting directly on raw birch, while adhesion would still not be an issue, we would be concerned about how the piece ages since it is so intimately tied to the life of the wood which will inevitably age as well, changing color and potentially having some surface checking – which are thin cracks that can develop along the grain due to expansion of the wood fibers in response to changes in humidity. For more on that see here:

Surface Checking and Plywood, Is It a Concern?

The above is not meant to cause undue alarm, we just like making people aware of potential risks even if they are small.

Hope this is helpful and if have any other questions just ask!

Thank you so much for this article and research! I get so anxious when I hear “recommendations” about watering down my paint, even though I never have issues with it. I have spent ages trying to find research that is evidence based so I can feel good about selling and exhibiting my work despite using watered down paints. This has helped me to feel so much better about experimenting and doing what works for my process!

Hello Emily,

You are very welcome. We are happy to help, and are glad this article has given you confidence to add water to your acrylics with a spirit of freedom! Enjoy!

Greg Watson

This is such a great article! I just want to make sure I’m reading this right since I also have been so scared of over watering my paint! Paint:water ratios (no medium added) 1:5 very safe, 1:10 quite safe, 1:20 generally ok.

“ If you simply want to take the guesswork out of it, you can always blend a minimum of 1 part GOLDEN Acrylic Medium, like our Fluid Matte Medium, Gloss Medium, GAC 100, or High Flow Medium, and 10 parts water. Then thin to your heart’s content. “

I have Golden Wetting Agent, can it be used to take out guesswork like those other mediums?

Thanks so much!

Generally you are reading it correctly, but we cannot speak for all acrylic paints on the market, so testing for your own application first is best.

Wetting agent is not a medium, but an additive, so it contains no binder and will not add binder to your mixture. Wetting Agent helps paint absorb into a surface better.

If you have any other questions, please feel free to email us at [email protected].

Brilliant article and valuable resource, thank you!! I too immediately thought of Agnes Martin’s diaphanous washes and also of Mark Rothko’s stain-like applications (in acrylics, as well as oils, the latter being another subject). My wish would be for a matte protection that did not alter the final paint appearance, yet afforded protection from scuffs, etc. I like working with very matte finishes, as per Ad Rheinhardt, albeit in acrylic, but always worry about potential damage in handling and display. Glass is out of the question as the super-matte finish would be compromised.

Thank you for this informative post. I am researching this topic because I am experimenting with applying powdered ochre pigments to cloth using diluted medium (the cloth will be embroidered but not laundered). I have GAC 100, and I would like to dilute it with water, mix it with pigment powder, and apply that to the raw cloth (without a coat of gesso first). Do you see a problem with the medium/pigment flaking off later on? I also have your fabric medium, but it doesn’t seem to mix well with dry pigments, so I’m looking for other options.

Hi Ruth –

When you say that you have our “fabric medium” are you referring to our Silkscreen Fabric Gel or GAC 900? That will simply help me know what else you have tried. That said, the fact that this is not meant to be laundered probably means you would be fine using other mediums. And yes, you can definitely get away with watering down the medium easily 1:1 with water and still have good adhesion. GAC 100 should be able to wet out any earth pigments very easily. You might try starting out making a workable paste using just water and pigment and then, afterwards, slowly adding in GAC 100 to make a very concentrated dispersion. You can quickly test the ratio of GAC 100 to the pigment paste by brushing some of the dispersion onto a piece of paper or cloth and letting it dry and seeing if it powders or easily rubs off. To make measuring and repeatability easier, and if you have a scale, try starting with a 1:1 ratio by weight of GAC 100 to the paste and adjust from there. Once you have the dispersion made, you could certainly thin further with just water or if needing to extend it out to get, say, more transparency, make a “medium” of 1:1 water and GAC 100 or, for something more water-like, try High Flow Medium in place of GAC 100, then add as much of that as you like. As you can imagine, there are a lot of variations you can play with and I would encourage you to do some playing with test samples. Finally see the following Tech Sheet for more information about using Golden Acrylics with Fabrics:

https://www.goldenpaints.com/technicalinfo/technicalinfo_fabric

Hope that helps and if you have more questions, just ask!

Thank you so much; this is super helpful and I will try your suggestions. In answer to your question, I previously used the GAC 900. And maybe with the 900 I could try mixing the pigment first with a bit of water to make a paste, in the way you described doing with the GAC 100. I’m guessing though that the diluted GAC 100 will work well for me. As you point out, testing is important, and I can try it with both mediums. Again, many thanks.

Thank you for this reply Sarah. (I replied to your post about 10 days ago but my reply has not been posted.) The fabric medium I used before was GAC 900. I did not dilute it and it had a somewhat sticky, plastic-y feel to it. I would be willing to try diluting it, since I have plenty left in the jar, but I also have GAC 100 on hand so I would like to try working with it (diluted) as well. I will try making samples with both according to your suggestions, which I very much appreciate. I’m looking forward to trying this out.

Hi Ruth –

Sorry about these delays. For some reason, the system thought your responses were spam – silly computer! Anyway, yes, do try diluting it – thinner is better in this regard as you will have a softer and less plasticky feel. Obviously more water the more transparent things become, but you can dilute a good degree and still have good adhesion.

And don’t forget that GAC 900 is meant to be heat set, which will also give it a soft hand. Check the tech sheet aI pointed to on using Golden Acrylics with fabric for guidelines on that. Also check this video as well:

https://www.goldenpaints.com/videos/fabric-painting-and-gac-900

Best regards,

Sarah

Thank you for this information! I always heard it was not safe to add more than 30% water to acrylic paint because it weakens the binder. Knowing about the pH level and the effects on biocides is also very useful. Is it safe to use soda ash (sodium carbonate) instead of household ammonia to the paint/water mixtures?

Hello XiXi.

You are most welcome for the information. Ammonia will evaporate out of the paint layer during drying. Soda Ash does not evaporate out during drying. This could lead to a powdery or crystallized residue on or in the acrylic paint layer. Therefore, we would not suggest swapping out ammonia for soda ash.

– GAC

Hi there!

Has a similar test been done with Oils (Williamsburg); how much solvent can you add? Because just as with water an acrylic, the same advice is often given for oils, because of the ‘sinking in’ of the oil; which for the acrylic will be its acrylic binder as well…

Are oil paint films weaker than acrylic ones of the same thickness?

How do they compare?

All my best,

M

We have not done that testing M. But have seen similar issues, in that highly diluted oil layers can be vulnerable to color lift. Also, dilute oils over absorbent surface can be even more extreme and dry to a dusty surface. Here is an article that compares oils and acrylics: https://justpaint.org/aspects-of-longevity-of-oil-and-acrylic-artist-paints/

Thanks,

G

I have seen similiar MEME some place (Vallejo?).

(Not “adhesion”, but “physical resistance”.

But it is said to be related to polyurethane component for acrylic-polyurethane primer product.

— — —

Of course the “adhesion MEME” is commonly seen.

I think the “Thinning will weak adhesion MEME” is just for unprimed situation.

Higher surface tension by water make it hard to wetting the workpiece. Thus weak the adhesion, but has little meaning for already primed ones.

(For Vallejo, the unprimed workpiece might be PS plastic.