Imagine if you will, the scene: the artist in their studio, clothing covered in paint, standing above, next to or on top of canvas laid upon the floor, fully animated and wild broad gestures halted by short deliberate movements; using their whole body to fill the enormity of the painting surface and capturing the physical movement, the action, the color, the emotion…

GOLDEN’s history with stain painters and the birth of Stain Painting runs deep and wide. In the 1940’s, Sam Golden (Mark Golden’s Father) made the first acrylic paint for Bocour, the paint company he co-owned with his Uncle Leonard Bocour. The paint was called “Magna” and was a solvent-borne acrylic. Sam later made water based acrylics named Aquatec. Morris Louis was one of the earliest painters to use Magna and he did so by staining. Many other artists during this time also used Bocour paints for staining including Helen Frankenthaler (who invented the “Soak-Stain” Technique), Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Mark Rothko, all with whom the Bocour/Golden family had direct relationships. Please refer to the sidebar in this article to read about the history of GOLDEN and stain painting in Mark Golden’s own words.

Creating a Stain Painting on a Raw Canvas Half Wetted with Water and Wetting Aid and Half Wetted with Water Only

While the word “stain” may bring up images of spilled wine or coffee on a tablecloth or rug, or soiled clothing from a hard day’s work; Stain Painting is essentially the same idea. Thinned paint is applied to raw canvas and allowed to soak in, just like stained clothing or wood stains. Although intentional, this technique lends itself to be full of surprises and “happy accidents” that can birth a new technique, a way of making marks or a new sense of control or chaos of the paint application. Because the paint absorbs fully into the untreated canvas, it becomes part of the canvas, interlocked into the warp and weft of the fibers and usually all the way through to the back.

This is truly a movement to make “art for art’s sake”. The true love of the materials dictating the act of applying the paint with the possibilities or limitations of the paint guiding the way to the final piece. This can be a basis, a ground if you will, for a more intricate composition painted on top or as it is for a simple, but thoughtful one.

Wash vs. Glaze:

While staining began as a technique using oil paints or solvent based paints, we do not recommend using these for staining, as the linseed, other oils or solvents penetrating directly into the raw canvas can cause darkening and embrittlement of the fabric over time. Instead, as modern materials developed, more artists moved toward using acrylics thinned with water for staining techniques. Thinning acrylics with water creates a “wash” as opposed to adding a medium into the paint, which is considered a “glaze” and has much more body. A “glaze” would likely sit on top of the canvas, whereas a “wash” absorbs in as a stain. Read our article, “Washes and Glazes: What When and How” for more information about a “wash” vs. a “glaze”.

Wet vs. Dry Raw Canvas and Absorption:

Usually with Stain Painting, the paint is applied to raw canvas by pouring or brushing in a wet-on-wet technique, or all at once, but can also be layered to create a different look. Once the raw canvas is fully saturated and dried, then the paint will no longer absorb into the surface; it will then sit atop as is the case when a primer or ground is applied for prep. The resulting sheen of a stain in raw canvas is very matte and flat. Stain painting is usually done horizontally, meaning the painting surface is laid on a table or floor. Since the paint is thinned with water, if created vertically, gravity will pull the paint down and cause it to drip. If desired, this can be lovely as a technique as well. If the canvas is pre-wetted and hung vertically, the fabric would likely sag unless temporarily stretched by stapling down to some wood with plastic sheeting underneath, so if the paint soaks through the canvas, it will not stick to the wood. Raw, untacked canvas on a table or floor may also buckle when dry, due to differing surface tensions.

Experimenting with different paint applications will provide different results. When applying paint to a dry canvas, the paint will at first sit on top and eventually sink in and the paint will stay in place, whereas applying the paint to a wet canvas, the paint will tend to flow and be much more active, soaking and bleeding into the water, which can sometimes result in looking very different from wet to dry. If applying only to one area or sporadic areas of dry canvas, when the wash has dried, the tension of the fabric will change in those areas due to the shrinking of the paint, which in turn can cause puckering and distortions of the canvas around the dried paint. This can make stretching the canvas after completion quite a challenge. Due to the sizing in the canvas from the manufacturer, washes or even just water applied to the raw fabric will not soak into the canvas right away. The sizing lowers the surface tension of the fabric, which causes the water with a high surface tension to remain on top or even to ball up and roll around. This can be remedied by scrubbing the paint into the canvas, essentially washing out or diluting the size.

Another way to break the surface tension is to add some Wetting Aid to the water used to wet the canvas and/or thin the paint. Wetting Aid is a surfactant or soap, which breaks the surface tension to make the paint or water “wet out” or absorb easier. Surfactant is an ingredient in all of our acrylic products so they do not reticulate on the surface. The paint will also behave differently with the addition of this surfactant in the paint or water. Instead of the paint being active and moving to the wet areas as readily, it will provide more control of the shape, line and edges of the paint applied and will result in a more even application with less change from the wet-to-dry appearance. This is also true when doing stains on paper, pre-wetted or dry. The origins of this product is also attributed to Sam Golden, who developed the first “Water Tension Breaker” product. The name and formulation has varied slightly throughout the years including; “Acrylic Flow Release”, “Wetting Agent” and now “Wetting Aid”.

Preventative Conservation:

If paint thinned with a lot of water is used for the stain technique, it would be recommended to protect the canvas from degradation down the line. The thin paint is akin to dying fabric and diluting the binder meaning there is not much acrylic resin in or on the canvas. The thicker the acrylic paint, the more the cotton or linen canvas is coated by a protective layer of binder, so when there is very little acrylic, the fabric may be exposed to the elements. The paint could also potentially be water sensitive, meaning if you brush another water based product on top of the extremely thinned paint, there may no longer be enough acrylic resin to hold the pigment down, resulting in potential color lift or bleed into the new and wet application on top. When using a wash on a very absorbent surface like raw canvas, water sensitivity is rarely an issue because the paint incorporates into the fabric, which tends to lock it down. Since it is nearly impossible to create a stained mark on top of a previously applied ground or other coating, best practice states that an Isolation Coat then Varnish, just varnish or even a medium, like Fluid Matte Medium or Matte Medium could be used on top to lock the pigments into place and coat the canvas resulting in a thicker paint layer that minimally changes the appearance, but can protect the painting from damage. One exception to this rule might be the Absorbent Ground. You may still achieve a stain look, but it will be different than directly on an untreated surface. Absorbent Ground also requires a Gesso application to the canvas first to aid with adhesion and flexibility. For further reading on canvas supports, read Mark Golden’s article, “Painting Supports: Cotton Canvas”.

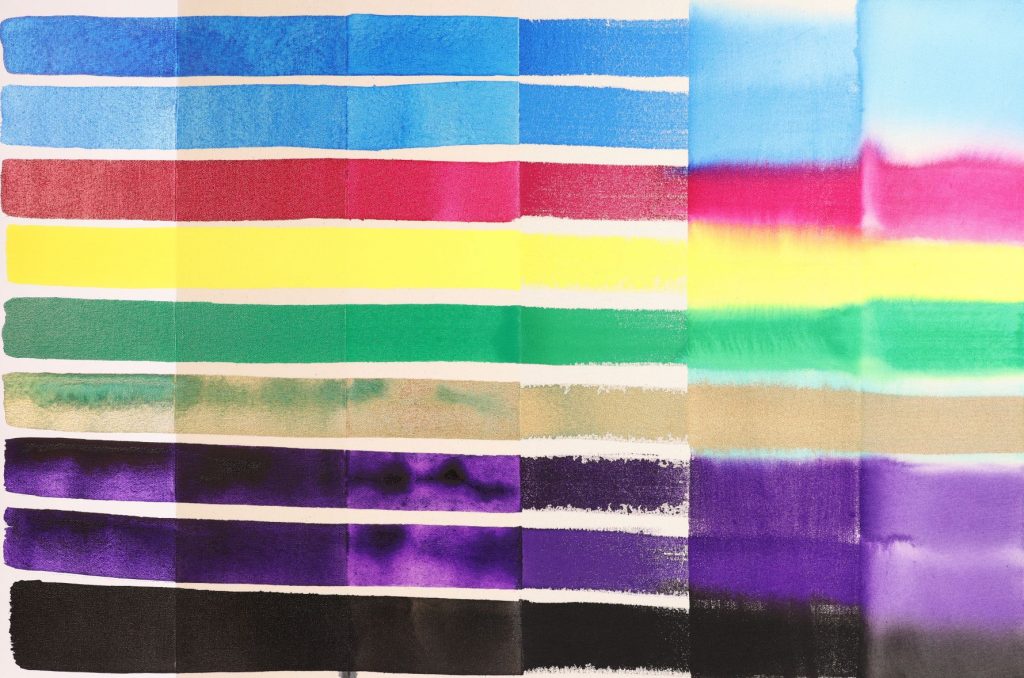

Paint Mixtures Applied from Top to Bottom in Images Below: Fluid Manganese Blue Hue: Water 1:2, Fluid Manganese Blue Hue: Water with Wetting Aid 1:2, High Flow Quinacridone Magenta: Water 1:2, SoFlat Bismuth Vanadate Yellow: Water 1:2, High Flow Permanent Green Light Unthinned, Heavy Body Iridescent Bronze: Water 1:2, Heavy Body Dioxazine Purple: Water 1:4, Heavy Body Dioxazine Purple: Water with Wetting Aid 1:4, High Flow Carbon Black Unthinned

Stain Painting can be a very exciting way to paint. It can be very physical and lovely surprises can give rise to new techniques. Every result is a learning experience and the more you do it, the more control you can have over the marks and composition. Don’t be afraid to get a bit dirty and dive into your canvas with your paint!

About Stacy Brock

View all posts by Stacy Brock -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

I have been stain painting my whole life. I received a BFA from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1972 and an MFA from NYU in 1977. In a number of my paintings I use masking tape to control the integrity of the image while staining color edge to color edge and letting accidents and interactions happen as a contrast between the two. Morris Louis and the other stain painters of the 60’s were very influential.

I especially like the hard edge I can achieve with tape and I even use the tape on paper as additional works of art.

Thanks so much for sharing your experience and technique for hard edges in Stain Painting, Denis! Happy Painting!

Thanks for reading and thanks for your feedback! You don’t necessarily need in depth knowledge to do a stain painting technique. You could simply prewet the canvas or scrub in the water thinned paint, but if longevity is a concern, some extra steps can be taken to stabilize the painting for the future. Thank you again!

Thank you!

do you have any Literatur where I can refer this technic, is for a paper.

Thanks in advance.

Estefania

Thank you for your question. Stain Painting should be included in any 20th Century Art History book. It may be helpful to look for literature about specific artists like Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Mark Rothko and Morris Louis.