Genuine Indian Yellow was prized for its transparency, depth of color and mixing properties with notable applications in landscape painting. Its origin was and is still, a curiosity. Recently, a 19th c. sample of Indian Yellow pigment was generously donated to Golden Artist Colors by Brian Baade, Paintings Conservator and Assistant Professor of Art Conservation at the University of Delaware. In a recent conversation with our Formulator Ulysses Jackson at an ASTM (American Standards for Testing Materials) Meeting, Brian mentioned he had come into a tiny amount of this Genuine Indian Yellow, authenticated using polarized light microscopy. Intrigued, we extended an offer to do some additional analysis of this sample in our lab and share the results alongside a comparison of our Williamsburg, GOLDEN and QoR India Yellow*. Thus a collaboration was born, one of many we have had with Brian over the years.

To have a genuine sample of Indian Yellow is an exciting opportunity for GOLDEN. For this article we hope to provide a brief history of this pigment for context and share the results of our scans so that conservators and enthusiasts alike can have a data set to add to their repositories.

*India Yellow (Indian Yellow): Golden Artist Colors will be changing the name of GOLDEN, Williamsburg and QoR Indian Yellow (hue) to India Yellow (hue) and within this article we will make reference to our products as such. To avoid confusion, when referencing historic “Indian Yellow”, we will refer to it by its historical name.

A Brief History of Indian Yellow

Tracing the origin of Indian Yellow Pigment has been a complex social and scientific endeavor spanning at least two centuries. Still, to this day, there is much debate as to whether Genuine Indian Yellow was fashioned from plant or from animal. It is not surprising there is confusion surrounding this pigment as its genesis has been obscured by myriad names, misattributed pigments, different grades of Indian Yellow and even the blending of this unique pigment with other colorants. The sole first-hand account of its manufacturing by T.N. Mukharji in 1883, described the raw material as being derived from the urine of cows fed a diet consisting solely of mango leaves and water. A diet toxic to cows and a process considered loathsome enough to be banned or fall out of favor in India as a result of religious preferences or changing cultural mores. After decades of research by scientists into metabolic processes and key biological markers, it is in fact likely Genuine Indian Yellow was produced as the popular story would suggest and was described by Mukharji. Recently, there has been renewed interest in the origin of Indian Yellow as one of the more mythic colorants and in light of the science there can be some irony in that it takes both plant and animal to produce this pigment.

Analyses of Genuine Indian Yellow

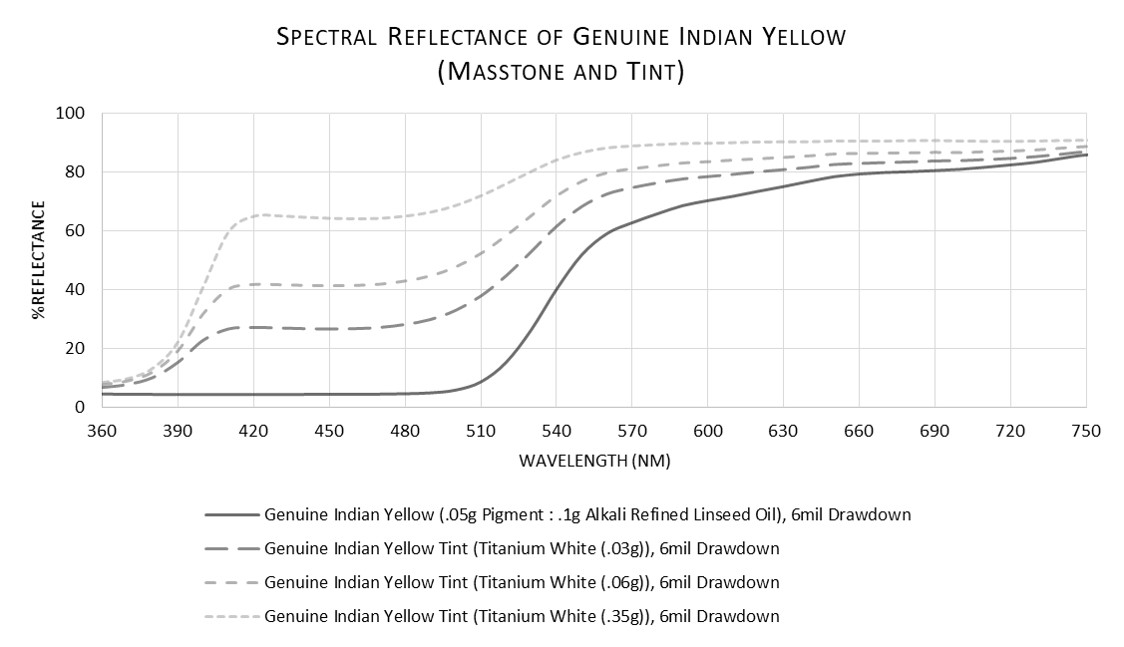

Below we have included a series of drawdowns of Genuine Indian Yellow pigment mixed with Alkali Refined Linseed Oil along with some tints using Titanium White. We chose to make oil paint for the historical data and have included Spectrophotometer and FTIR scans of these samples with some direct comparisons to our Williamsburg Oils, GOLDEN Acrylics and QoR Watercolor.

Drawdowns

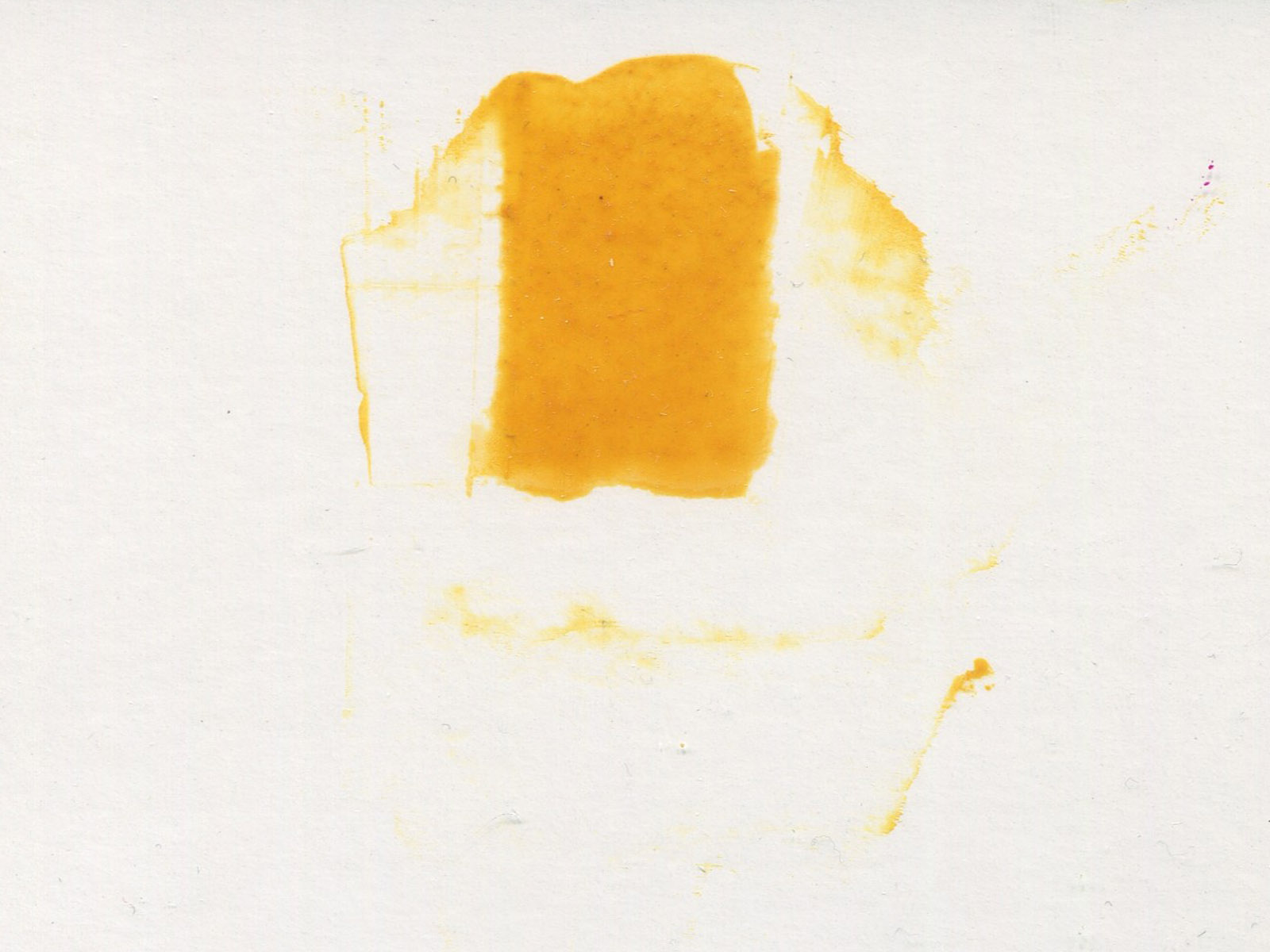

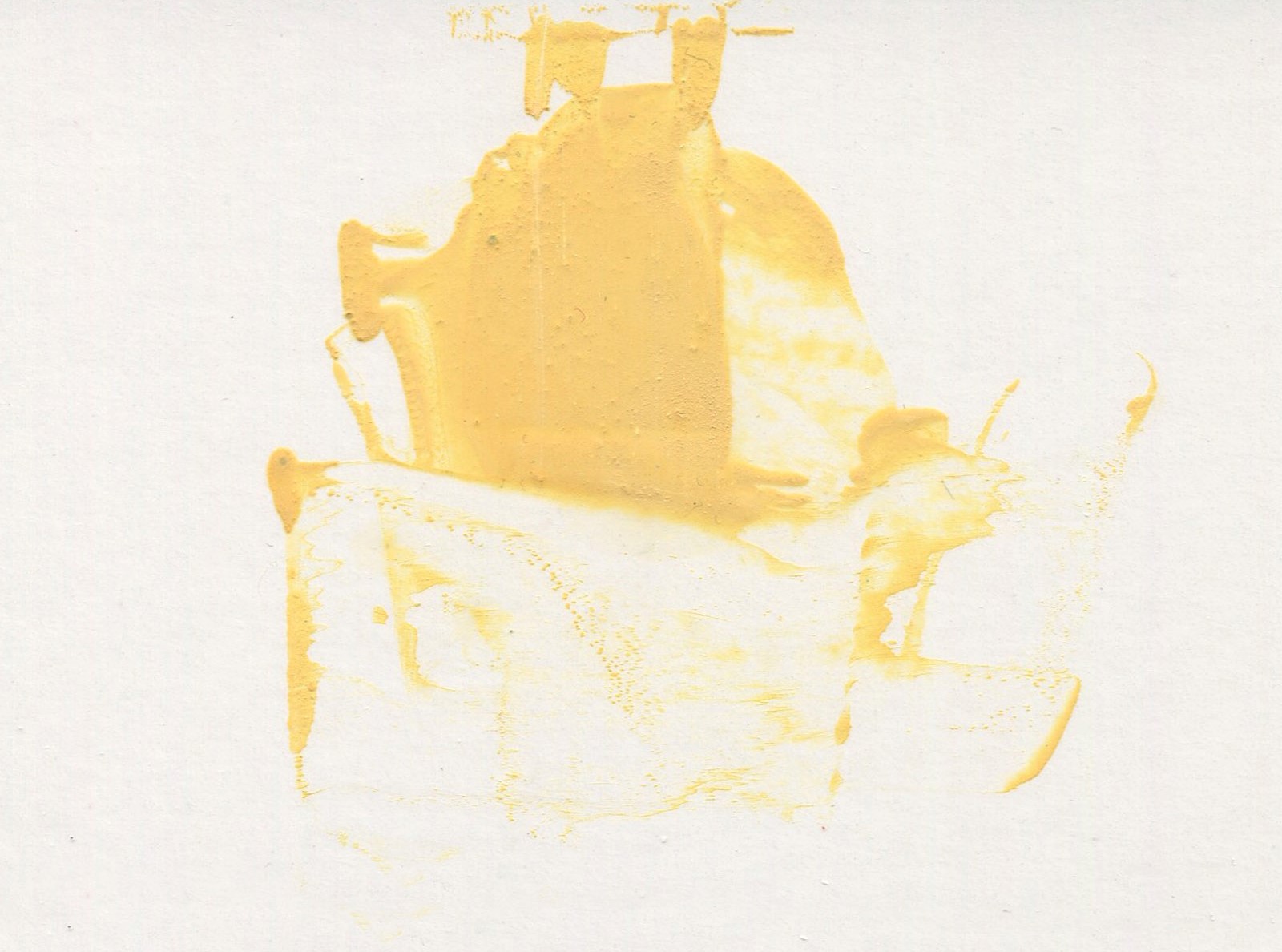

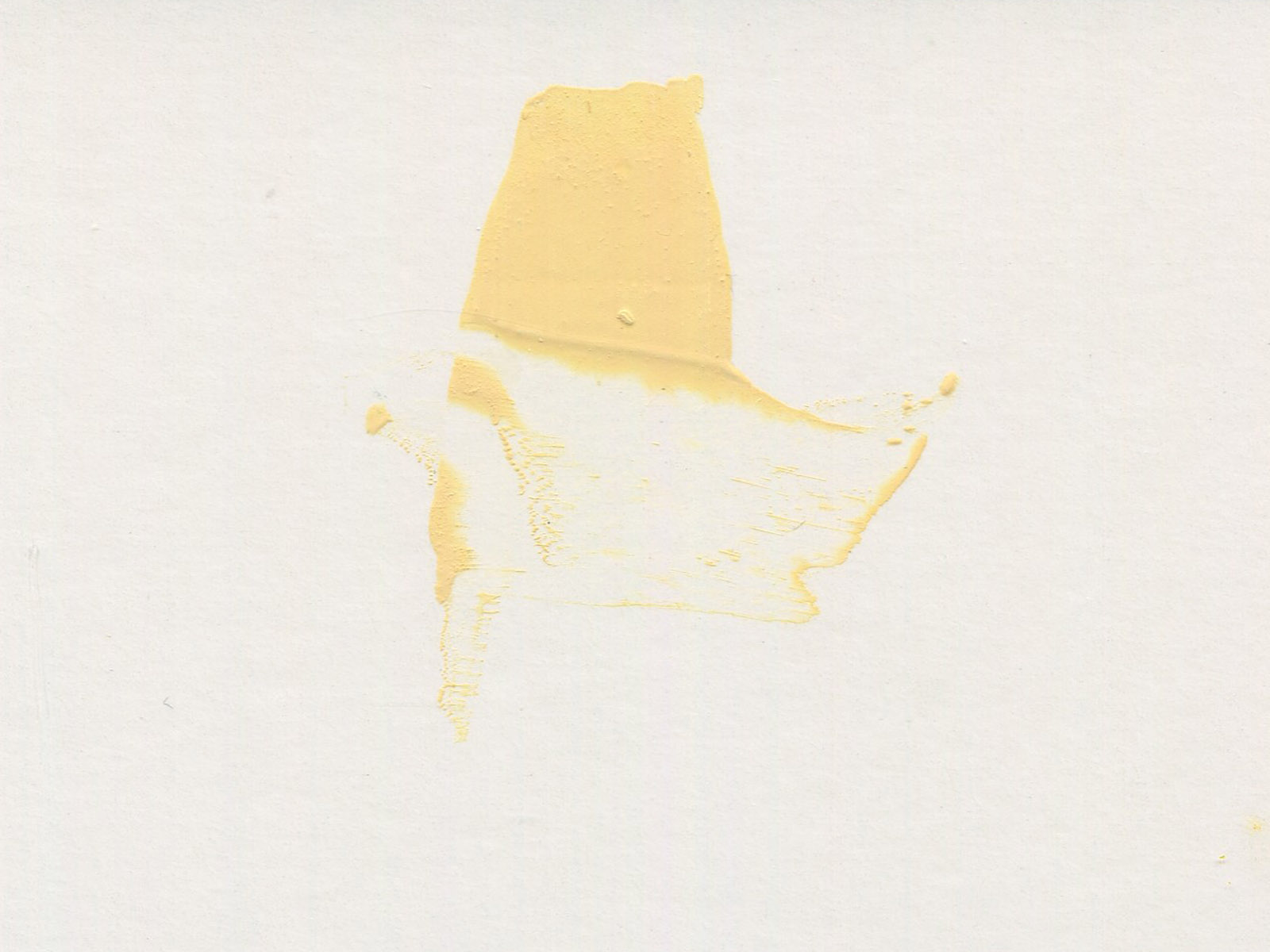

In image A we have Genuine Indian Yellow as a 6mil drawdown where you can get some sense for the transparency and masstone at a thickness similar to a brush application. In images B, C, and D, different amounts of Titanium White were added to see what this sample would look like as a tint and to assess its tinting strength. Due to the rarity of our sample of Genuine Indian Yellow we cast smaller drawdowns than typical.

Spectrophotometer

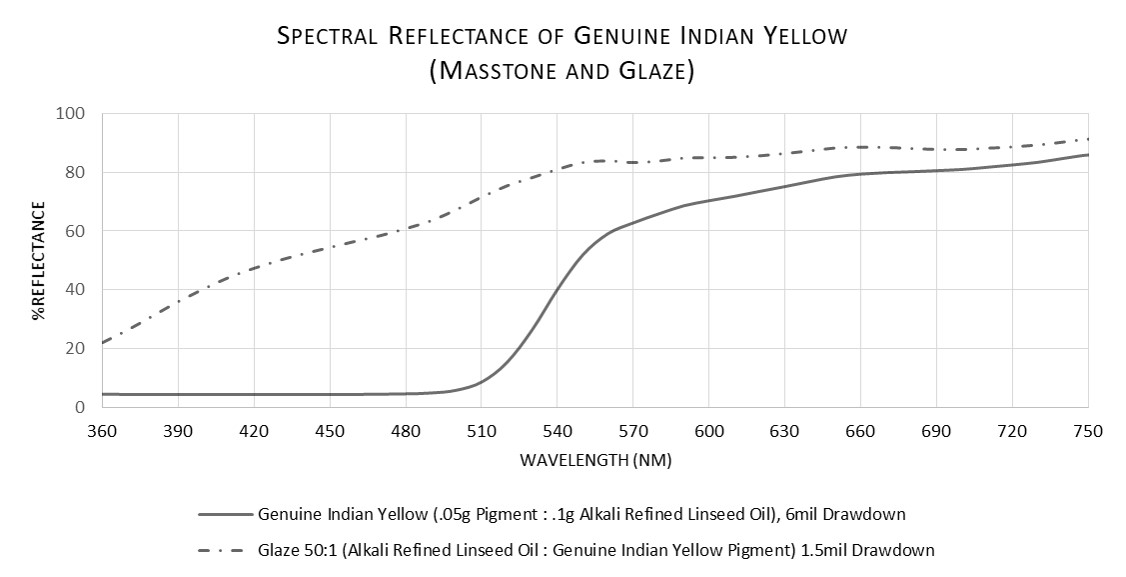

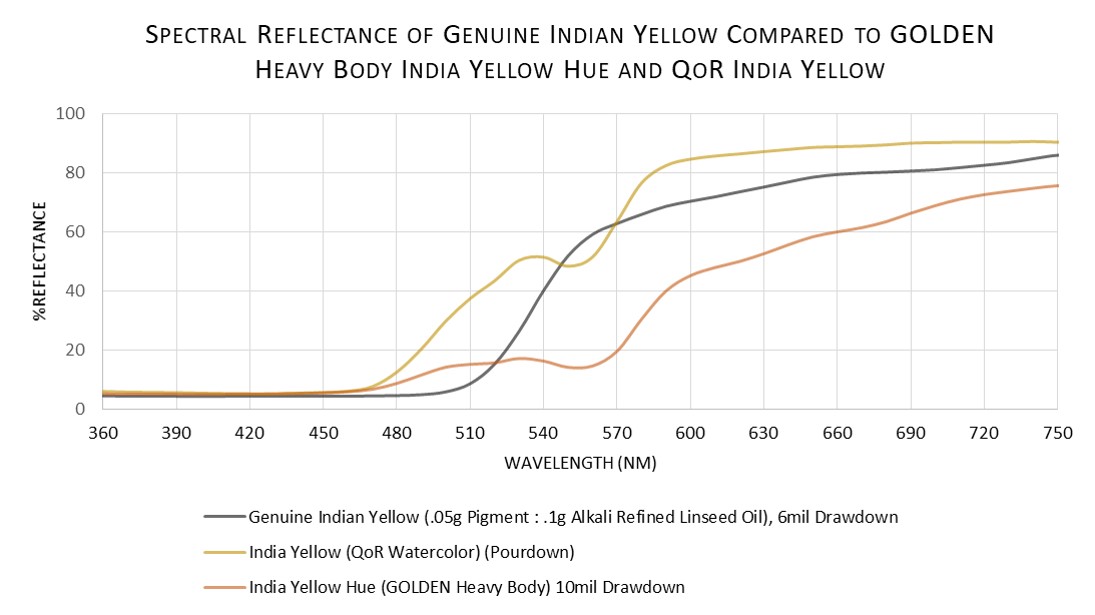

The Spectrophotometer as a tool allows us to measure how light interacts with a particular sample. Different colors will reflect light in different intensities at different wavelengths. This allows us to “measure” the visible range we perceive as color, which can be an asset in applications such as color matching and lightfast testing. Below we have compiled a series of reflectance curves of Genuine Indian Yellow as compared to its Tints, a Glaze and our versions of India Yellow from Williamsburg, GOLDEN and QoR. We have included a link to an Excel file that contains the data from our scans on an Xrite CI7800 as well as these graphs.

Click Here to Download Spectrophotometer Data Set

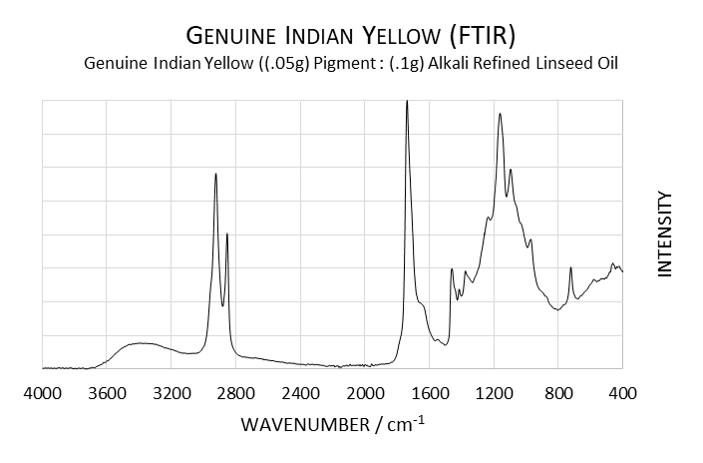

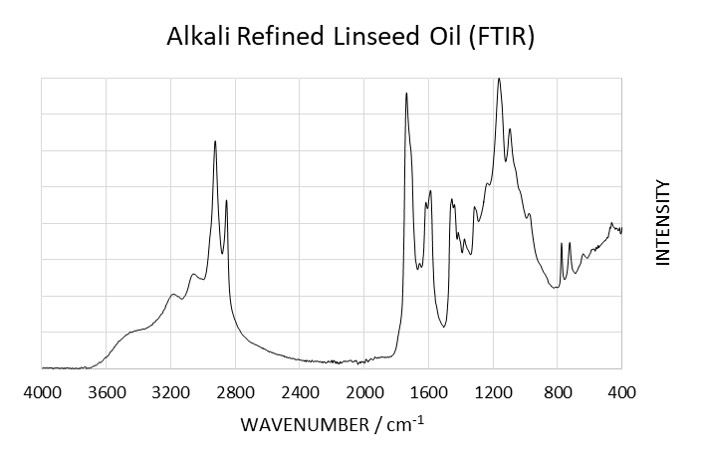

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy or (FTIR) is a tool that allows us to measure the “signature” of a particular sample as Infrared Radiation (IR) is passed through it. By measuring the absorption and transmission of IR, it tells us the different chemical structures present, which serve as unique identifiers. As a comparison, the Spectrophotometer will give us a color profile by measuring the reflectance of light on our sample. The FTIR scan will give us insight into the chemical structures that make up our sample. That being said, without an FTIR database and computer analysis, very little can be gleaned from these curves by looking at them. Still, we offer FTIR scans of Genuine Indian Yellow in Alkali Refined Linseed Oil as well as a separate scan of the Alkali Refined Linseed Oil on its own. We have also included an Excel file that contains the data from our scans on a Bruker Alpha II ATR as well as these graphs.

Click Here to Download FTIR Data Set

Acknowledgements

We would again like to thank Brian Baade for sending GOLDEN this sample of Genuine Indian Yellow and for being such a great resource and friend. We would also like to thank Ulysses Jackson for doing what you do and a special thanks to Trevor Ambrose for collecting and organizing the data used for this article. It has made it possible for us to share this information with the public, which is a unique opportunity and something we at GOLDEN love doing.

References

De Faria, Dalva L.A., et al. “A Definitive Analytical Spectroscopic Study of Indian Yellow, an ANCIENT Pigment Used for Dating Purposes.” Forensic Science International, vol. 271, 2017, pp. 1–7., doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.11.037.

Ploeger, R., et al. “Late 19th Century Accounts of Indian Yellow: The Analysis of Samples from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.” Dyes and Pigments, vol. 160, 2019, pp. 418–431., doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.08.014.

Ploeger, Rebecca, and Aaron Shugar. “The Story of Indian Yellow – Excreting a Solution.” Journal of Cultural Heritage, vol. 24, 2017, pp. 197–205., doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.12.001.

Smith, Gregory Dale. “Cow Urine, Indian Yellow, and Art Forgeries: An Update.” Forensic Science International, vol. 276, 2017, doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.04.013.

About Scott Fischer

View all posts by Scott Fischer -->Subscribe

Subscribe to the newsletter today!

No related Post

Very interesting post. It is a shame that you don’t provide bibliography about the manufacturing process of Indian Yellow. I was really under the impression that the cows being fed mango leaves was a myth and everything I have read recently points in that direction. Maybe there is new studies that I have not read … yet. Love also that you shared your data. Thanks a lot for the post and all the information in the blog.

Hello Paulo,

At the bottom of the article we include our sources in a bibliography section. The two by Rebecca Ploeger and one with Rebecca and Aaron Shugar offered nice synopsis of research into the manufacturing process, especially the “The Story of Indian Yellow – Excreting a Solution”. Check them out! It seems that as the science has evolved, there is mounting evidence that the story is likely true. Glad you like the content, we love sharing our testing when we can.

Sorry but i didn’t notice that the papers in bibliography related to that, and only noticed after downloading them and not before making the comment. Thanks for the answer!

No worries Paulo, happy we could share them and for your interest in following up. Don’t hesitate to reach out!

Scott

Really interesting article! Knowing the history of the color and getting some insight into the likely manufacturing process is fascinating. I believe that using urine as a processing ingredient is not that outlandish; historically, much indigo was processed with urine (and still is in some places). Even religious mores would probably not have interfered with such manufacture. Love the graphs and data as well. The title of the article The Story of Indian Yellow… is hilarious in the context of usually buttoned-up scientific titles. And finally, that this info can allow clarification of art forgery is just plain fascinating, and could be the plot of a movie.

Yes, Richard it is a humorous article title and an appropriate one! We are glad you enjoyed this and we agree the subject is certainly worthy of a film! It is actually amazing how much research was dedicated to this subject and in some ways there is a trickle of humor there as well.

I am delighted you published the visible spectral data for this interesting pigment. Which instrument, make and model, did you use to perform the measurements?

Hello Robin,

Thanks for reaching out. We added these to the article for you. We used an Xrite CI7800 for the spectrophotometer and for the FTIR we used a Bruker Alpha II ATR. Hopefully that helps! Let us know if you have more questions.

Best,

Scott

HI there,

I have had the pleasure of recently sorting the archives of Cornelissen and Sons in London (Colourmen since 1855) and found in them, two large balls of Indian Yellow, plus another jar of smaller balls… I realise my contribution will provide not an once of scientific evidence… but can tell you opening those jars (probably sealed some 30/40 years ago) was like entering a barn! A very pungent smell indeed… not unpleaseant but most certainly reminiscent of a cow shed and enough to convince me the story might indeed be no legend!

Just thought I’d share for fun!!

Thank you for sharing Sabine!

Sabine, Those are some of the samples that Rebecca Ploeger and I sampled for our study. We would love to talk with you more about what you found. Can you email us to chat?

Thank you for the article and reader comments. It is a wonderful blending of subjective apprehension and scientific analysis. Learning about the history of the materials we use enables us to imagine the possibility of connecting to the sensibilities of artists who used them in the past.

Very interesting article. Why didn’t you do a lightfastness test against Williamsburg and QoR versions of India Yellow. It would be interesting to see where in relation to Alizarin Crimson, the genuine Indian Yellow falls in regard to lightfastness.

Hello CF,

Due to the uniqueness and size of our sample of Genuine Indian Yellow, we did not have enough available to cast large drawdowns in triplicate like we would for standard Lightfast Testing. We agree it would be a nice addition to the article to have that data set. We will pass this along to the lab though and if we get more in it is certainly on the list of things we would like to do!

Scott

Just fascinating. I love the history and science behind the pigments we use. Thanks for sharing this.

It was fun writing it Hal, we are glad you enjoyed it!

In this modern age when anything seems possible, how is it that the original substance is not analyzed and recreated synthetically? There would seem to be a demand. I for one would definitely buy a good transparent orange yellow like in old hand coloued flower prints. Have tried various modern offerings, but nothing so beautiful.

We have tried to mimic the working properties and color space using our India Yellow Hue, but the challenge you speak of has a lot to do with lightfastness. Recreating something that is akin to a genuine Indian Yellow, but that is more stable and lightfast as paint is challenging. It might be possible to find a dye-based colorant that gets to an even higher intensity, but it would not be as lightfast as a pigment. The availability of pigments of high lightfastness within a particular color space limits the pool to choose from as well. One of the graphs in the article shows how close we were able to come to recreating the same spectral curve of the genuine sample. We agree Genuine Indian Yellow is a lovely color and that color space is dazzling and very useful for mixing colors as well! Thanks for the post!

Scott

Thanks Scott, very nice of you to give a thoughtful reply. Still, I have two old books, e.g. Mrs. Loudon’s on annual flowering garden plants, hand coloured plates, the yellows , 1843, should be gamboge, Indian yellow – yet they don’t seem faded at all. Lovely yellows that I can’t duplicate. Since most brands of watercolour paints know that Indian yellow stands for something desireable, something good, and since one can buy synthetic indigo, synthetic alizarin, I wondered if there was an opportunity for someone to synthesise the actual chemicals in old Indian yellow. Or possibly try processing mango leaves another way, or maybe through cows with due regard to their wellbeing. Cheers, Seb

That sounds like an interesting book Seb. We agree with everything you said! What was interesting during our research, was just how many papers were dedicated to the origin story of Indian Yellow. If there is sufficient interest, maybe there will be some synthetic alternative in the future. We all love a good story! Thanks for sharing with us Seb!

PY108 euxanthic acid, the main component in Indian Yellow, is a commercially available pigment.

Thanks for the note M. We will pass along to the lab in case they are unaware of this option. We like to bring in pigments routinely to see how they perform.

Scott

Thanks Scott, We’ll have to leave it at that – unless I get off to India and nose around. Of course there is the practical problem of how to collect cows urine – tie on a bucket? Cheers, Seb