Please Note: What follows is an update to long-term testing that we first wrote about in 2018. The original articles provide important background and context for understanding the current results, and can be found here: Zinc Oxide – Reviewing the Research, Zinc Oxide – Warnings Cautions and Best Practices, and FAQs Concerning Zinc Oxide (PW 4) in Oil Paints

The cracks were sharp-edged and clean, happening while you carefully bent the paint film across the metal rod, then slowing down once you felt the slightest resistance, until suddenly it would simply snap in two, like a potato chip. You recorded the results, then reached for the next sample, sensing how this one was much more flexible, almost rubbery. It was just a matter of ratios, really, the two samples differing solely by a few percentage points of zinc oxide. It seemed so negligible on paper, and yet the results spoke to an undeniable and clear difference between them. And it is precisely the invisible dividing line between that difference, which we are still trying to locate.

When we wrote about the issues surrounding zinc in 2018, the most important unanswered question was whether there was any level of zinc that was safe. As we noted then, there was little if any information anywhere that was based on studies of artist’s paints. That is a gap we hope to fill, and what follows is a first look at a new round of test samples after two and a half years of natural aging. None of the results will be definitive – at this point it is still too early in the process – but so far Titanium White with 2% zinc appears to be flexible, while 5% is already showing signs of brittleness. Mixtures of Lead White with zinc, on the other hand, have raised concerns even at the 2% level. And then, of course, there are the differences in how they yellow. Below we will unpack all this in more detail, and discuss the testing that supported our results.

Brittleness

Over the last 20 years the main concern with zinc, and zinc blends, has been their tendency to form very brittle films, even in a relatively short time. For artists this raised the questions of how much, how quickly, and was there a safe percentage one could use in a mixture? Especially with reference to Titanium White, where additions of zinc greatly increase its whiteness and help counteract its tendency to form weak, soft films and stringy paint. While film hardness and stringiness can be addressed through other additives, the synergy between titanium and zinc that allows it to create particularly white, less yellowing films, has proven hard to match.

To test brittleness we created Lead and Titanium White paints with various amounts of zinc, from a minuscule .1% to a maximum of 5% by weight. Based on prior testing, we felt that was the upper limit that might be used before causing substantial embrittlement. The paints in the following tests were made using only pigment and alkali refined linseed oil, with only the percentage of zinc vs titanium or lead changing from sample to sample. This way we could limit the variables and make sure the results were solely caused by the differing ratios of the pigments. We then cast 6 mil drawdowns, which are uniform films of paint about the thickness of two sheets of copy paper, on top of GOLDEN Acrylic Gesso, Titanium Oil Ground, and Lead Oil Ground that had been applied to polyester film. For the last two and a half years, starting in May 2019, they have been naturally aged indoors in ambient lit conditions.

Test Apparatus

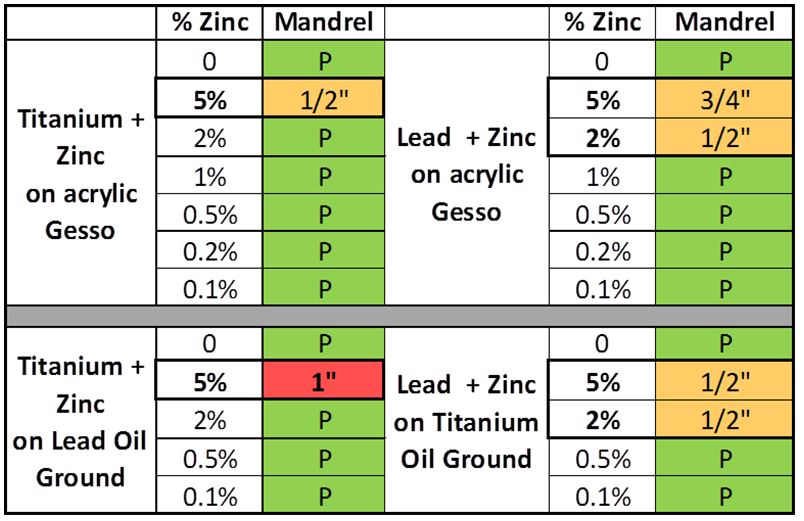

Testing was carried out using a Gardco® Pentagon Mandrel Test Apparatus, where a paint film would be bent over various diameters and then examined for cracking after each one and recording the results (Image 1). Anything showing cracks at the largest diameter of 1″ was considered failing, while anything above 1/2″ and below 1″ was considered a cautionary sign for possible increases in brittleness in the short term.

Below are the results, where you can see that only one combination failed at 1″, while a few others had warnings at the 1/2″ or 3/4″ diameters (Table 1). However, there are other important things to note. The main concerns were limited to paints having higher zinc percentages, particularly at the 5% level, which is where we predicted problems might start to appear. The two lead-zinc combinations, on the other hand, show concerns at both the 2 and 5% levels, and while not failing, it is a strong indicator of increased brittleness compared to other samples. This is important because, as mentioned in our earlier article on Zinc Oxide – Reviewing the Research, the technical literature points to combinations of lead and zinc as being particularly more brittle than others. And indeed, we had shown that our Silver White, which was a combination of lead and zinc and has since been discontinued, was among the most fragile paints that we tested. So this seems to bear that out, even at levels much lower than the Silver White had at the time. It is also interesting that the one outright failure involved a 5% titanium-zinc blend on top of a lead ground, suggesting a possible interaction between the two. Certainly something to look for in later rounds.

different grounds after 2.5 years of aging.

Does any of this raise concerns about our current Williamsburg Titanium-Zinc White, which also has a 2% level of zinc? Not so far. All the titanium-zinc blends below 5% have performed well, and as mentioned, we no longer make any Lead Whites that contain Zinc and would generally recommend that artists avoid that combination. Also, given the results, we might suggest some caution around using zinc-bearing colors on top of lead grounds, just to err on the side of safety until we understand that better. But so far, even there, nothing below 5% has had issues.

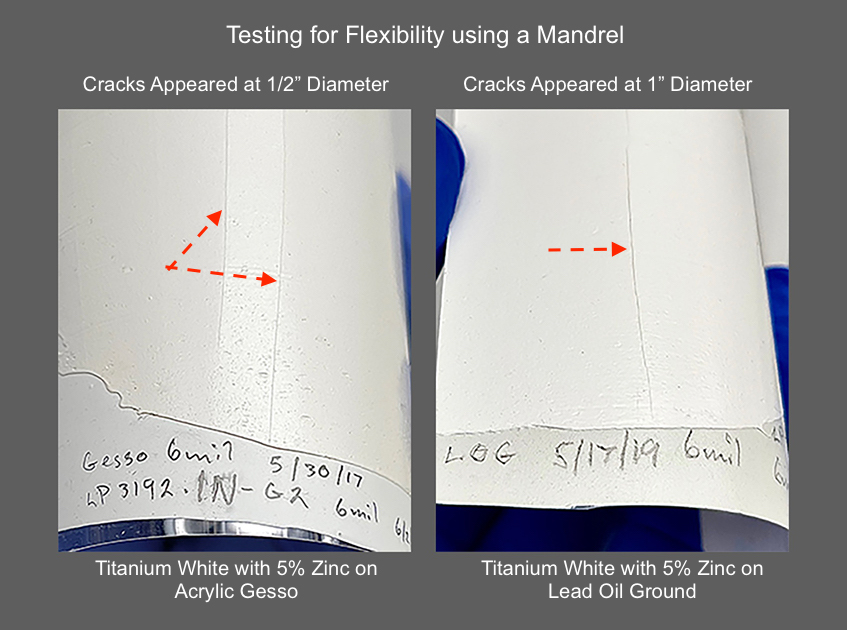

To give a visual sense of the brittleness we saw, the image below shows the cracks that happened with the 5% titanium-zinc blends on top of GOLDEN Acrylic Gesso and Lead Oil Ground (Image 2).

after 2.5 years of aging indoors.

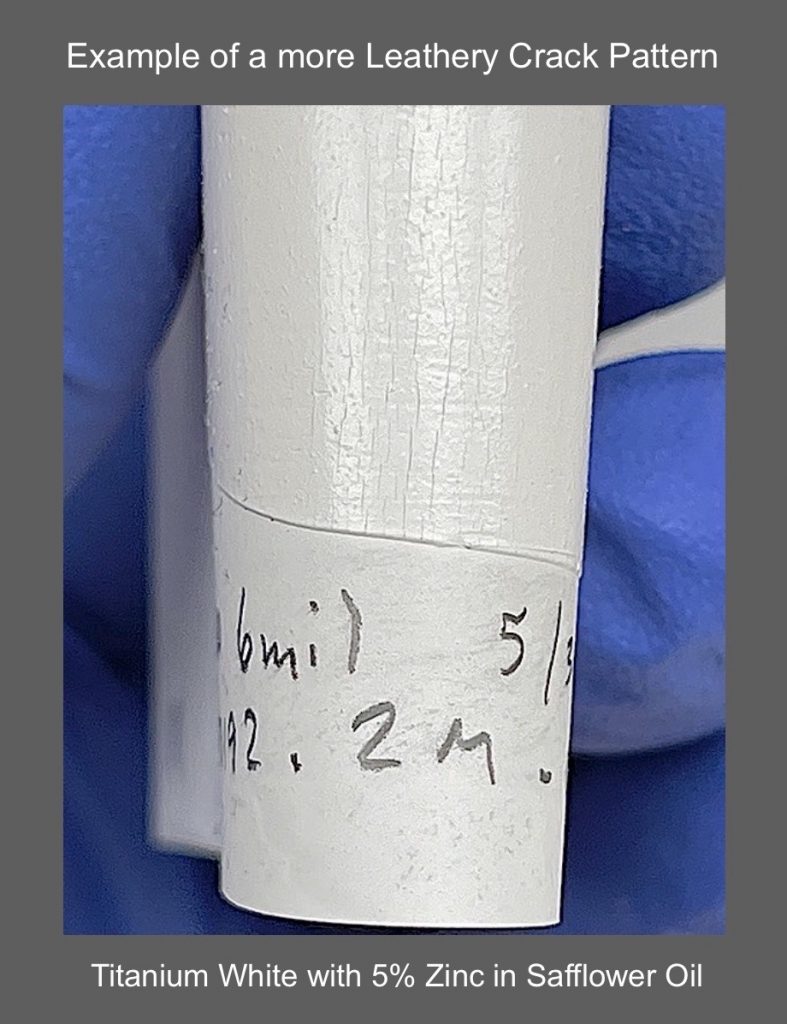

Compare that to the leathery crackle-like pattern you find in this safflower-based Titanium White with 5% zinc (Image 3). Here the softer, less reactive nature of the binder counteracts some of the brittleness we saw above. As a result, the paint has remained just rubbery and pliant enough that instead of a sharp single crack, one gets a whole array of short ragged ones covering a wide strip across the surface. It evokes the worn surface found on old leather belts.

It can be tempting to discount all these types of cracks as being the result of extreme testing, in this case, bending a paint film over fairly small diameters – certainly smaller than anyone would expect in the normal course of things. However, the point in this type of testing is not to recreate some action an artist might do, but to put paint under a controlled amount of stress so we can get a very early glimpse into a process of embrittlement that can often take decades to fully unfold. In the worst cases, that type of process can lead to severe surface cracking and delamination, simply from the normal stress and strains of environmental changes or the act of handling and shipping. So these tests serve as the early warning signs of something still off in the distance, but catching our attention and making us watchful. And of course, just as importantly, are all the other samples that passed with lower percentages of zinc, many being folded nearly in half over a 1/8″ metal edge with still no issues. So clearly the higher level of zinc is causing this brittleness, even at this early stage. The remaining question is simply whether some percentages will prove safer than others. As time moves on and these samples age, we will be able to see whether these lower percentages start to grow more brittle or remain stable.

Zinc and Yellowing

The issues with zinc overlap those of yellowing since Titanium-Zinc White is almost always much whiter than Titanium alone, which feels like an obvious improvement. But is there a minimum amount that provides enough of that benefit without requiring the higher percentages that appear linked to embrittlement? Is the trade-off worth it?

We ran multiple ladder studies adding tiny amounts of zinc to both lead and titanium, starting from a minuscule .1%, then increasing in small steps to a maximum of 5%, the upper limit we had set for the tests on flexibility. These mixtures were also composed solely of pigment and alkaline refined linseed oil, as a way to limit the variables and isolate the impact of zinc. That said, a more fully formulated Titanium-Zinc would have performed better and more evenly.

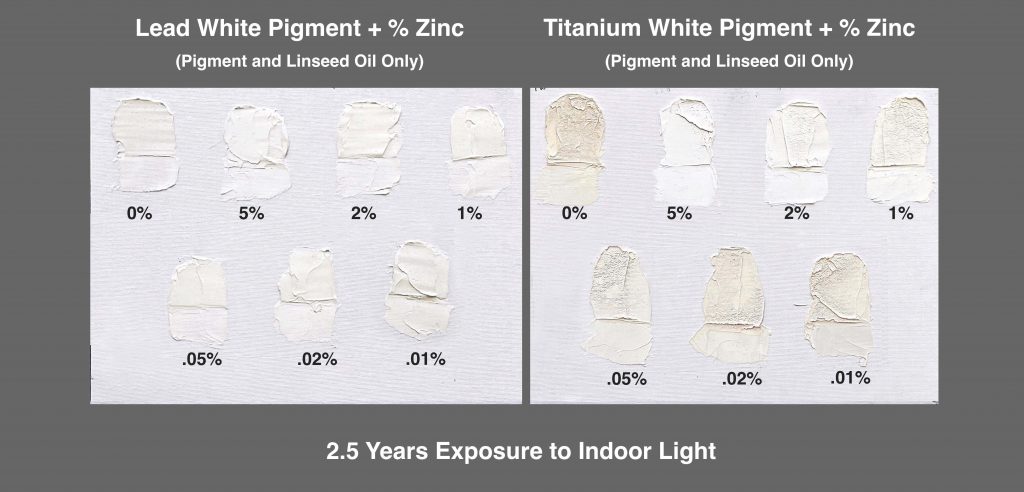

The following two canvas panels will give you a quick sense of how zinc impacts yellowing, particularly with titanium (Image 4). Here the 2 and 5% blends stand out sharply from the rest of the series, and while the 5% level produced the whitest result in the thicker areas, in the thinner sections the 2 and 5% paints seemed nearly identical.

Titanium and Lead Whites after 2.5 years of indoor aging.

It’s also worth pointing out the severe surface wrinkling seen in the thicker areas of the titanium samples, especially for anything below 2%, although even that had the slightest amount in the topmost area where it was thickest. This is caused by shrinkage due to the loss of volatile components after an outer skin has formed while drying. The larger additions of zinc keep the paint open longer, allowing for a more even through-dry. The lead samples, on the other hand, display equally smooth surfaces with no sign of wrinkling, even without zinc. Lead is simply much more effective in bonding with the linseed oil, including the more volatile elements, while the lead soaps that develop in the curing process provide a more stable structure.

Conclusion

As we suggested at the beginning, these results are at best provisional, a review of testing that could easily span decades before providing more definitive and longer term results. But there is still enough here, we hope, so you can begin to form some educated guesses and sense where your comfort zone might lie. For ourselves, we continue to think 2% zinc is a reasonable limit, which is also the current guideline we adhere to for our Williamsburg Titanium-Zinc White. At the same time, we will always follow the research and make changes to our formulations or recommendations as needed. And currently we would recommend caution if using blends of lead and zinc, as well as anything with zinc on top of a lead ground until these are better understood. Despite everything, titanium zinc can still play a role on the artists’ palette, and clearly brings some unique benefits – albeit with risks of embrittlement that are real but still being researched to see if a safe level exists.

I appreciate your testing this. However have you looked into the variety of Zinc White that you’re testing. Acicular (or American/Direct process) Zinc White has a history of greater durability than the finely divided and more commonly available French process Zinc White that was introduced after WWII.

“The Victorian Branch of the Oil and Colour Chemists’ Association held a meeting in Melbourne, Australia in the summer of 1949 to discuss a sudden and marked increase in problems associated with house paint formulations containing zinc oxide pigment, and to investigate any possible relationship between this increased failure rate and recent changes in manufacturing methods for the pigment.”

“C.H.Z. Woinarski, then Senior Chemist at Hardie Trading Ltd., outlined the shift in paint production and performance observed during World War II, when new methods of pigment manufacture emerged—at newly built or converted facilities—to meet an increased demand for zinc oxide pigment. Direct Process (also called American Process) methods of pigment production were replaced by Indirect Process (sometimes called French Process) methods, and this manufacturing shift was accompanied by a precipitous rise in failure rates of oil‐based house paints containing zinc oxide pigment produced using the new method.”

“Nelson confirms that Direct Process oxides contained various percentages of acicular variations on the crystalline form, some joined to form “twins” and “threelings” (referred to as “brush‐heap” formations by Bussell), while Indirect Process zinc oxides (often marketed under the term “Seal” oxides) were typically irregularly shaped particles of uniform size distribution.”

See this report:

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/95784/Rogala_Dawn_V_-20180502-ROGALA_1949_Symposium_METAL_SOAPS_2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hi CF –

I replied more fully on MITRA, where I saw that you posted a longer version of this question, asking about any research comparing direct (French) and indirect (American) processed zinc, and wondering if perhaps the Pre-Raphaelites might have used the acicular zinc that the direct method produced. So let me go ahead and simply paste a lightly edited version of that reply below, even though it goes somewhat far afield from the more narrow and streamlined question above.

In terms of research in this area, I am not aware of anything outside the types of historical, commercially focused ones referenced in the article by Dawn Rogala that you link to at the bottom of your question, as well as another one by her from 2011, Industrial Literature as a Resource in Modern Materials Conservation: Zinc Oxide House Paint as a Case Study. There are several reasons that are likely for this. Most of the research on paint is driven by the commercial industry which has a very different set of concerns, centered around a much shorter time span, than conservation or artists in general. Add to that the fact that latex house paints were introduced in the 1940s and would eventually supplant oil-based ones as you get into the 1980s, you find that most of the fundamental research into traditional oil based paints basically starts to disappear in the 1950-60 period. Lastly, the indirect process has largely dominated the artist paint market because it is a purer product, with fewer contaminations. This is particularly true with lead, which usually appears in trace amounts when zinc is processed from ores. Unfortunately, it takes only a very small amount of soluble lead (on the order of 5 ppm) for it to trigger a health warning. I was told that many years ago, when we first looked into getting this pigment for testing, we were unable to locate anything under that threshold but we are reaching out again to see if anything has changed.

On whether the Pre-Raphaelite’s might have used acicular zinc, let me share why I think it is doubtful. First, the French indirect process was discovered in the 1840s and considered a major innovation that quickly spread throughout Europe and was adopted by both commercial and artist paint manufacturers. So any later import from the US would have to overcome this early lead and established market. Plus the Pre-Raphaelites were formed right in the middle of this period, in 1848, and most of their major works date from the 50’s. This is important as the American direct process was only discovered in 1852, and it took to 1860 for processes to be worked out and production to be at a commercial scale. So definitely coming late to the Pre-Raphaelite party. Plus in 1865 you have the Civil War! Let’s just say that supplying the European art market with pigment was not high on the list of priorities and most production was diverted to the war effort.

In terms of that article by Dawn Rogala which you linked to, concerning a 1949 Symposium, there are a few things that I can point out and draw your attention to. The most important one is to realize that Rogala is merely reporting on what the attendees to that symposium were presenting – she is not supporting their findings as being true, simply that such and such was said. Which makes it easy to confuse things and take the passages at face value. Much of her interest in commercial symposiums are not necessarily that the findings are factual, per se, but that the conversations around the research and the topics being thought about and discussed foreshadow the ones that now dominate current conservation and that things can be gleaned from them worth pursuing.

In the paper from 2011 that I mentioned earlier, Industrial Literature as a Resource in Modern Materials Conservation: Zinc Oxide House Paint as a Case Study, Rogala actually makes clear that this type of commercial literature is fraught with bias as they are presented by the manufacturers themselves within a competitive context, each vying for advantages.

Just to share a couple of quotes from that, which actually reference the same 1949 symposium:

Lastly, just to make it absolutely clear, I bring all of this up not as a way to beat up on acicular zinc, but only to show that things are usually more complex than they seem. But hand’s down, acicular zinc definitely should be examined and tested – no question. And we are sympathetic to the desire to find an overlooked process or material that can bolster the argument for zinc, or render it safer. And like you and others we scan the literature looking for clues and so truly appreciate it when folks share what they have found as well. We’ll keep digging on our end of the tunnel and see if we can all meet up somewhere!

Hope some of this helps.

Sarah Sands

Senior Technical Specialist

Golden Artist Colors

I very much appreciate Golden doing these tests.

Thanks Sarah.

Hi Ron –

You are so very welcome. And I know you have been one of the faithful followers of our testing over many years and I truly do appreciate that as well.

Could it be possible that mixing this 2% zinc white paint mixed with another pigmented color that dries to the harder end of the scale, might also be pushed beyond the ideal limits, though the zinc percentage is lowered still further?

Hi Mark – My immediate response, informed by 26 years of head-scratching while studying oils, and accompanied by a slight chuckle, is who knows, at this point, it seems anything is possible! But more seriously, I think combinations with a range of other colors are something we still need to look into. Certainly, we know that zinc mixed with lead will form a particularly brittle film – which is counterintuitive when recalling that lead forms the most flexible film of any pigment. So, just given that fact, I am not sure if the hardness of a color will be the key more than its chemical interactions. As you can imagine, part of the difficulty in this research is just how complex it can become. But we will keep chipping away at it.

Dear Sarah,

Thank you for your report on investigations into the embrittlement of Titanium/Zinc White oil paint films. However, a number of issues struck me as being unexamined and needing further elaboration. For example, you state:

“The paints in the following tests used a basic formula of pigment, alkaline refined linseed oil, beeswax, and barium sulfate with a minimum amount of drier, with only the percentage of zinc vs titanium changing from sample to sample”.

My question relates to the experimental design. Why were beeswax, barium sulfate, and drier (an undescribed type) added and used in the various formulations? I thought the number of variables being tested should be predicated on varying only the percentage of zinc oxide pigment used. Even at a fixed percentage in all the formulations employed, could barium sulfate, or the beeswax, or the unnamed drier have an effect upon embrittlement? I felt it might be important to examine the role that these other ingredients have in addressing the proverbial “elephant in the room” question about how to configure the investigation itself. In other words, why wasn’t a control set of samples included, which had the same gradated amounts of zinc oxide pigment present, but made without barium sulfate, beeswax, and the drier, also run? Thanks for the feedback and best wishes on your continued experimentation.

Hi Michael – First a thousand and one thank you’s for pointing this out as in fact what you caught was a mistake on my part – an overlooked mismatch between the description of the paints vs the actual table and data I wrote about!! I have adjusted the text accordingly while the table that was shown was already the one based precisely on a series of blends using only pigment and oil for all the reasons you mentioned. While we did do parallel testing on the types of basic paints that were described, those are not included here and, in any case, roughly followed a similar pattern. You can sense the inadvertent mismatch later on when I describe the tests on yellowing and state that those “mixtures were also composed solely of pigment and alkaline refined linseed oil”, clearly a reference back to a prior group. So yes, you were absolutely right to call out the elephant in the room – which thankfully sent me running back to the article where I was relieved to discover, after careful double-checking, that it was merely the ghost of a prior elephant that had somehow strayed onto the scene.

Again, cannot thank you enough for pointing this out. One benefit of writing for JustPaint is that I have a thousand editors willing to hold me to account.

Viva elephants! 🙂 Mike R.

Do these same sort of issues present themselves in acrylics? I’m also curious if applying oils over, say an under painting of acrylic Zinc would similarly interact, especially with Lead.

Hi Randy – In terms of embrittling acrylic paints, no. The interaction is solely limited to oils and alkyds due to the nature of how zinc interacts with drying oils.

As for painting with oils over acrylics having zinc in them, the simple answer is we don’t really know and will need to test this combination. Luckily Zinc is not commonly used in acrylics since a transparent white can be created easily with a medium or gel, but until we truly have data on it, we would advise caution about painting oils on top of anything that contains zinc, including acrylics, just to err on the side of caution.

Hi Sarah,

And how about zinc in egg tempera – any concern with brittleness there?

Thanks, as always, for your commitment to artists and their materials, and the research that you and Golden do.

Koo Schadler

Hi Koo – I would be the first to admit that we do not really have any testing on egg tempera’s interactions with various pigments, and my knowledge of the literature in that area is also very spotty. I would think Brian Baade or Kristen deGhetaldi, over at MITRA, might be better equipped to answer this.

And thank you for the warm words about our testing and contribution. We certainly love offering what we can.

Sarah

You’re the best, Ms. Sands. You always go the extra mile.

But, I wasn’t the one posting on MITRA. Someone was quoting what I’d originally posted on WetCanvas (Antonin). I didn’t read your answer there until now ;).

“…in 1834, just two years after the paint company was founded, Winsor & Newton introduced a calcine zinc oxide which they called ‘Chinese White’ (named after the type of porcelain that was popular in Europe at the time). It was heated at high temperatures and was denser and more opaque than other whites available.” Many years ago, I remember reading articles that specifically stated that the original WN Chinese White was the Acicular form of Zinc White. I had never heard that term before.

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/05/286340.pdf

The pigment crystal morphology is said to play a role in the brittle fracture of zinc oxide:

“The use of the acicular form of zinc oxide (American process) leads to a very considerable improvement and gives much more durable paints than the amorphous (French process) zinc oxide which consists of small round particles. “Instead of the end of their life being signalised by the usual checking of the film, such paints showed no signs of it and finally began to disintegrate much later by chalking.”

“And further;

…in the case of acicular zinc oxide paint, failure “begins with small uniform cracking which relieves strain and prevents more intensive failure”, and that very high acicularity is undesirable because it involves too high an oil absorption.”

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiworeQxuT0AhXxGDQIHQuBAsEQFnoECAcQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmajemac.com%2Fzinc-oxide-zinc-dust-a-twenty-year-staple%2F&usg=AOvVaw0oAzpedtFmkm_PSCI3PZRb

“There are two processes used in producing pigment grade zinc oxide, the American process and the French process. With the American process, a more acicular particle is derived as opposed to the French process which is more nodular in structure. Typically, the acicular pigments are less reactive in coatings systems and are therefore considered more stable.

Grade 417W is an acicular, American process pigment which provides the maximum in stability and a narrow particle size distribution. It is our most commonly used coating grade and is maintained in inventory in our Clearwater warehouse.”

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi12L6JpeT0AhWDKzQIHcYrBkoQFnoECBYQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fedisciplinas.usp.br%2Fpluginfile.php%2F4986468%2Fmod_folder%2Fcontent%2F0%2FZnO.pdf%3Fforcedownload%3D1&usg=AOvVaw01JD4Uk1jruI63H37BGfGZ

The particles are nodular in shape and the individual primary ZnO crystallites are 30–2000nm in size. Scanning electron microscope images of typical French process ZnO are shown in Fig. 5. The surface area of French process ZnO is generally 3–5 m2 g−1 but can reach 12 m2 g−1 by carefully controlling combustion conditions such as air flow and flame turbulence or the distance between the suction hood and nozzle (which affects the air velocity). If the flame temperature increases, the specific surface area will drop. By increasing the excess of reactant air (oxygen) by making a better circulation of air or forced flow of compressed air in the combustion zone, ZnO quenching becomes faster and finer particles can be achieved, resulting in higher specific surface area.”

“There are various implementations of the French process. Older technology principally uses a batch process that takes place in a crucible with a long cooling duct, most of which is horizontal. Newer technologies use a semi-continuous process with a vertically-designed cooling duct to save space. A batch is recharged with zinc ingots at approximately four hour intervals whereas in the semi-continuous process a zinc ingot (often 25 kg) is added to the furnace every 6 min. The productivity of the semi-continuous process is often higher than that of the batch process. The semi- continuous system is rarely shut down unless for an overhaul and it is generally very compact.”

“3.3. Morphology of zinc oxide particles

The morphology of ZnO particles can be controlled by varying the synthesis technique, process conditions, precursors, pH of the system or concentration of the reactants. A wide variety of shapes are possible. The French and American process zinc oxides have nodular-type (0.1–5m) or acicular-type (needle-shape, 0.5–10 m) particle shapes. Wet-process ZnO may have a sponge-like form with porous aggregates being up to 50m diameter. There are, however, a large number of other morphologies, each produced under some specific set of conditions. Many of these have been given whimsical names. The possibilities include nanorods, nanoplates , nanosheets , nanoboxes , irregularly-shaped particles, polyhedral drums , hexagonal prisms, nanomallets, nanotripods, tetrapods, nanowires, nanobelts, nanocombs and nanosaws, nanosprings and nanospirals and nanohelixes, nanorings, nanocages, nanoneedles, nanotubes, nanodonuts, nanopropellers, and nanoflowers.”

There’s an illustration in the article that shows some of these variations. Could one or more of these morphologies provide a more stable Zinc White?

http://www.daryatamin.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Pigment-Compendium-Set-Pigment-Compendium-A-Dictionary-of-Historical-Pigments.pdf

These are excerpts from the Zinc Oxide entry:

“Variations in particle morphology in zinc oxides have been identified and are divided into two main types. The acicular-type crystals, which occur as individual, twinned or tetrahedral combinations, are found in zinc oxides derived from the slow burning of zinc vapour, as mentioned by Kühn, usually from the French process. The nodular-type particles are the most common and have a more rounded appearance, being produced from faster burning syntheses. The manufacturing methods yield different grades of pigment based on particle size which are sold under different brands of Seal. Varieties which require little oil (usually those with larger particle size) are often known as ‘zinc white double’ or ‘zinc oxide double’.

However, Kühn also states that drying processes, particle morphology, impurities and lattice defects are also now known to play an important role on the photochemical properties of zinc white.

Although zinc white is stable in light, studies have shown that it tends to saponify the fatty acid component of certain oils, with the degree of soap formation being dependent upon the particle size of the pigment, with the finest particles resulting in more rapid soap formation.”

Perhaps something was lost between the original French process and the current French process that involves “space saving” and “semi-continuous” techniques, resulting in a more finely divided and reactive pigment.

Hi CF – Many of these sources are ones we know about and we are on board with the thought that this might offer a more stable film – or at least something that fails less dramatically since micro-fissuring and chalking are not exactly a great selling point. But then perhaps those issues could be overcome. However the real block in pursuing testing of this line of zinc is not needing to be convinced, but the fact that the pigment from all the suppliers we have contacted reveals too high a level of basic lead carbonate. Now, it might be that some people would be willing to use a Zinc White containing a Lead Warning, but we feel it presents issues. And of course one would need to assure people that there is no embrittlement not simply over the short term but further out, and given the current concerns with Zinc, that would present a high hurdle to overcome. But we will continue to look and examine this area.

Perhaps it would be useful to do a series of tests on trying to make a titanium white based paint without zinc and lead but with different additions to see if one could be made without so much yellowing or embrittlement?

I am thinking of various percentage additions of: Zinc Sulfide, Strontium Titanate, Calcium Carbonate, Kaolin, Barium Sulfate, Hydrated Calcium Sulfate, Hydrated Magnesium Silicate.

Richard

Hi Richard – In terms of yellowing, we have done testing with a good number of formulations but not necessarily all the ones you mention, and we definitely know that other additions besides zinc can improve yellowing. For example look at Image 5 in our article On the Yellowing of Oils from 2019 and you can clearly see the improvements. But always room to test other combinations.

In terms of embrittlement, Titanium White doesn’t have an issue except when zinc oxide is added, so really no need to adjust a zinc-free Titanium White to improve flexibility, although without some form of addition you can get a very soft, somewhat sticky film.

Hi Sarah,

I meant to include beeswax in my comment as I remembered you had found good results with it! I was wondering if another material would strengthen the film and/or reduce the yellowing. That’s why I was thinking of a comprehensive set of tests 🙂

I know it’s a bit of a cheat but Permawhite included a very small amount of ultramarine blue to counteract the yellowing.

I have a commercially prepared stretched linen canvas primed for oil paintings.

The label states that the canvas was first double-sized, then primed with zinc bound in linseed oil,

then primed again with titanium. Should I be worried about using this canvas, because

it was primed with zinc first?

Hello Martin,

While there are some who claim that pre-primed canvases with zinc or titanium/zinc are fine, we have seen enough embrittlement from zinc pigment to err on the side of caution. Keep in mind, that zinc can cause issues even when it is buried under other layers of oil color. The zinc can cause other layers to become brittle and in some cases can push other layers off the surface!

We hope this helps!

Greg

This is so helpful – are you planning on doing any longer term testing on the sub-2% formulations?

We still have the testing from this article. We will need to review it again to see if there are any changes in flexibility and cracking. There’s also the newest article about Zinc with Stand Oil instead of refined linseed oil.

– Mike